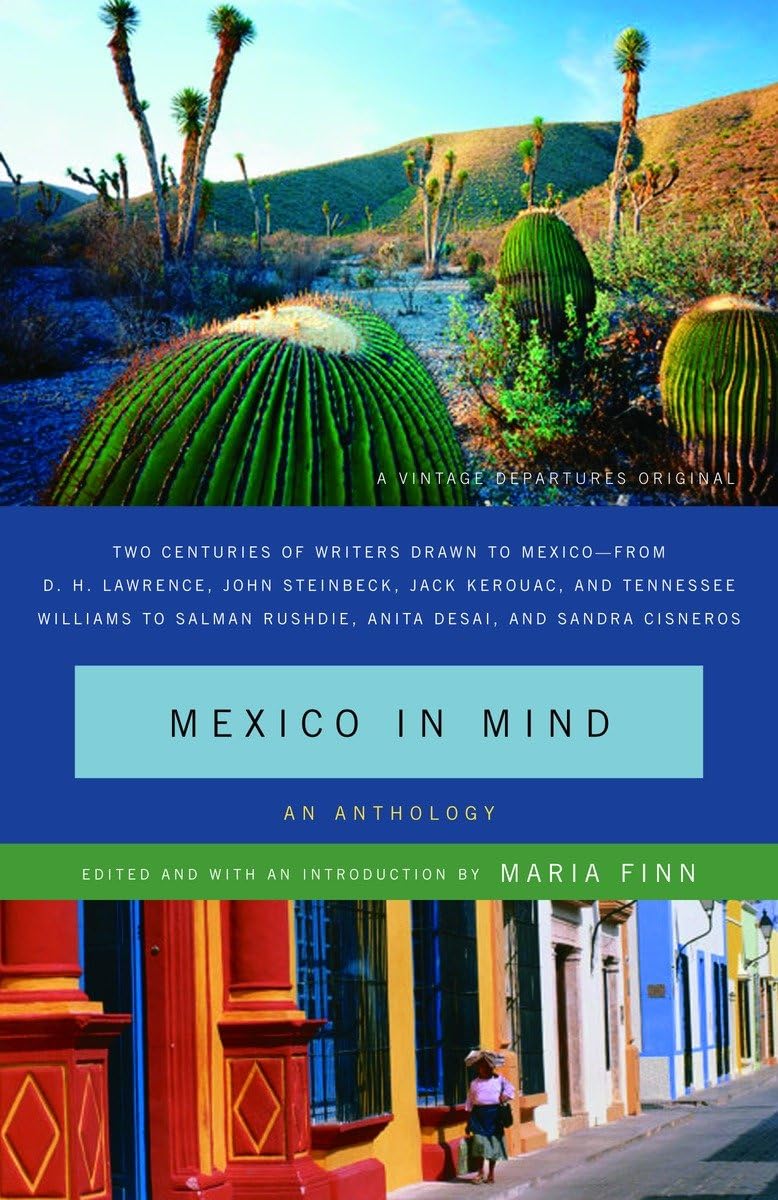

Two centuries of writers drawn to Mexico—from D. H. Lawrence, John Steinbeck, Jack Kerouac, and Tennessee Williams to Salman Rushdie, Anita Desai, and Sandra Cisneros This scintillating literary travel guide gathers the work of great writers celebrating Mexico in poetry, fiction, and nonfiction. Ranging from 1843 to the present, Mexico in Mind offers a remarkably varied sampling of English-speaking writers’ impressions of the land south of the border. John Reed rides with Pancho Villa in 1914; Graham Greene defends Mexico’s priests; Langston Hughes describes a bullfight; Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs find Mexico intoxicating; Alice Adams visits Frida Kahlo’s house; Ann Louise Bardach meets the mysterious Subcommandante Marcos face to face. Fictional accounts are equally vivid, including poems by Muriel Rukeyser, Archibald Macleish, and Sandra Cisneros, short stories by Katherine Anne Porter and Ray Bradbury, and excerpts from John Steinbeck’s The Pearl , Tennessee Williams’ Night of the Iguana , and Salman Rushdie’s The Ground Beneath Her Feet . From the bustle of Mexico City to coffee planations in remote Chiapas, from Mayan ruins to the markets at Oaxaca, the scenes evoked in this anthology reflect the rich variety of the place and its history, sure to enchant vacationers, expatriates, and armchair travelers everywhere.Alice Adams • Ann Louise Bardach • Ray Bradbury • William S. Burroughs • Frances Calderón de la Barca • Ana Castillo • Sandra Cisneros • Anita Desai • Erna Fergusson • Charles Macomb Flandrau • Donna Gershten • Graham Greene • Langston Hughes • Fanny Inglehart • Gary Jennings • Diana Kennedy • Jack Kerouac • D. H. Lawrence • Malcolm Lowry • Archibald Macleish • Rubén Martínez • Tom Miller • Katherine Anne Porter • John Reed • Luis Rodriguez • Richard Rodriguez • Muriel Rukeyser • Salman Rushdie • John Steinbeck • Edward Weston • Tennessee Williams Maria Finn is the editor of the anthology Cuba in Mind (Vintage, 2004) and author of a memoir about falling in love and marrying her cab driver in Havana, Cuba. She has written for Audubon, Saveur, Metropolis, The New York Times, and the Los Angeles Times, among many other publications. She has an MFA in Creative Writing from Sarah Lawrence College and has published literary work in magazines such as Gastronomica, The Chicago Review, New Letters, and Exquisite Corpse. She has lived and worked in Alaska, Guatemala, and Spain, and traveled extensively in Latin America. Alice Adams (1926-99) Alice Adams is the author of ten novels and five collections of short stories, including Careless Love (1966), Superior Women (1984), Caroline's Daughters (1991), Almost Perfect (1993), A Southern Exposure (1995), and its sequel, the posthumously published After the War (2000). She's known for looking at the lives of contemporary women, exploring the nuances of both their professional and personal worlds and the intersection of the two. Adams traveled annually to Mexico for approximately thirty years. In this excerpt from Mexico: Some Travels and Some Travelers There (1991), she is inspired by an exhibit of Frida Kahlo's art in San Francisco to visit the artist's home, now a museum. Kahlo's art reflects both her love for Mexico and her often painful love for fellow artist Diego Rivera. She has become an icon for the suffering artist. According to Adams, "Two words often used in connection with Kahlo are narcissism ('All those self-portraits') and masochism ('All that blood'). Both seem to me quite wrongly applied. I rather believe Kahlo painted herself and her images of personal pain in an effort to stave off madness and death." When I thought of a return trip to Mexico City, with some friends who had never been there before, I remembered the Camino Real, which would be as far out of the fumes and the general turmoil as one could get, I thought-with advertisements featuring three swimming pools. And this trip's true object, twenty years after my first contact with her, was Frida Kahlo: I wanted to make a pilgrimage to her house, and I had talked two friends into coming with me-Gloria, a writer, and Mary, an art critic. All of this more or less began in the spring of eighty-seven, when there was an extraordinary exhibit of Kahlo's work at the Galería de la Raza, in San Francisco. So many painters' work is weakened by its mass presentation in a show, but this was not so with Kahlo's work: The overall effect was cumulative, brilliantly powerful, almost overwhelming. Her sheer painterly skill is often overlooked in violent reactions, one way or another, to her subject matter, but only consummate skill could have produced such meticulous images of pain, and love, and loneliness. I began to sense then, in San Francisco, a sort of ground swell of interest in both her work and in her life-and the two are inextricable. Kahlo painted what she felt as the central facts of her life: her badly maimed but still beautiful body, and her violent love for Di