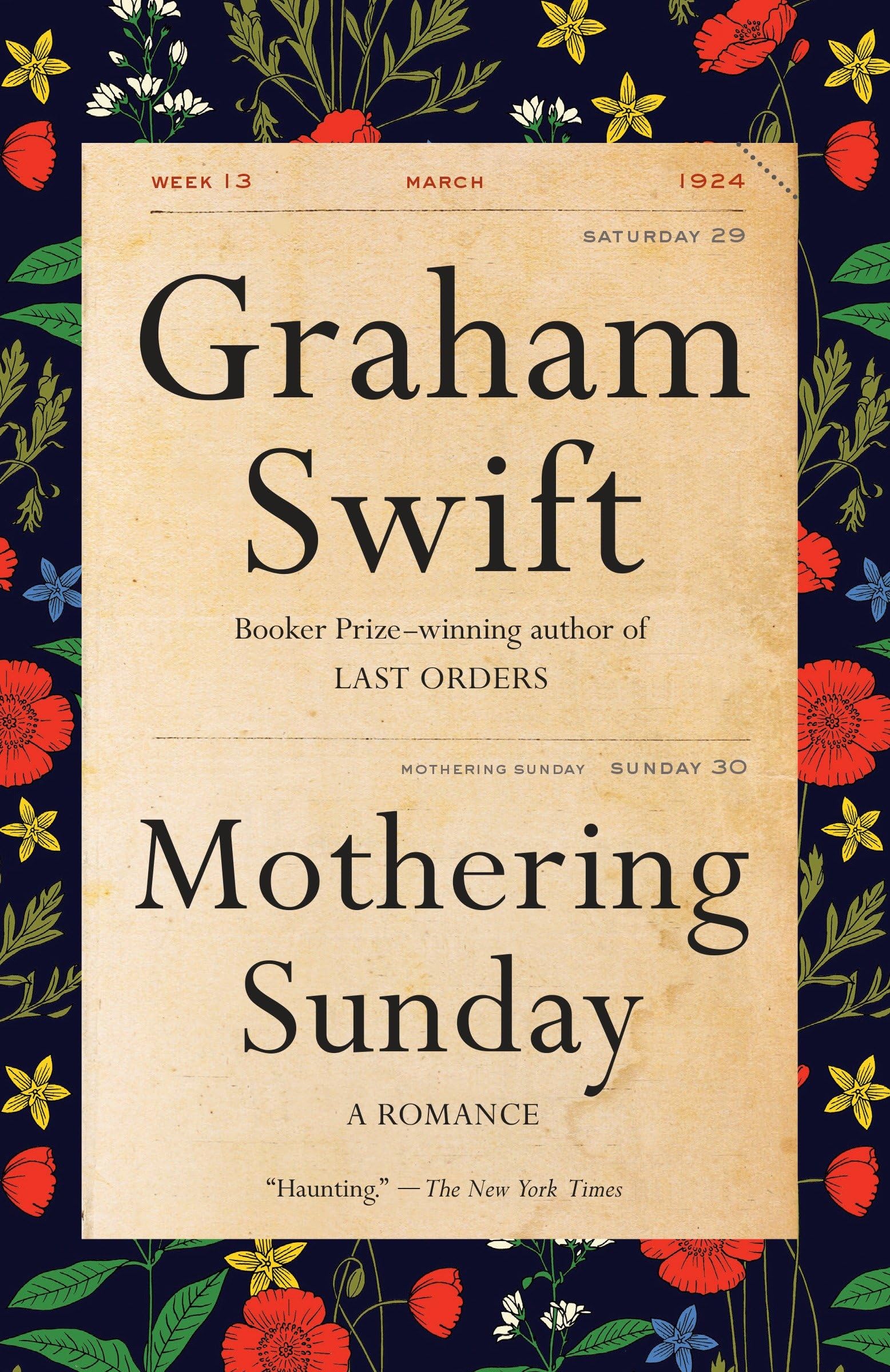

From the Booker Prize-winning author, an intensely moving tale that begins with a secret lovers’ assignation in the spring of 1924, then unfolds to reveal the whole of a remarkable life. • Don’t miss the major motion picture starring Odessa Young, Josh O’Connor, Ṣọpẹ́ Dìrísù, Colin Firth, and more “Exquisite ... shows love, lust, and ordinary decency struggling against the bars of an unjust English caste system.” —Kazuo Ishiguro, The Guardian On an unseasonably warm spring day in the 1920s, twenty-two-year-old Jane Fairchild, a maid at an English country house, meets with her secret lover, the young heir of a neighboring estate. He is about to be married to a woman more befitting his social status, and the time has come to end the affair—but events unfold in ways Jane could never have predicted. As the narrative moves back and forth across the twentieth century, what we know and understand about Jane—about the way she loves, thinks, feels, sees, and remembers—expands with every page. In Mothering Sunday , Swift has crafted an emotionally soaring and profoundly moving work of fiction. “Haunting.” — The New York Times “Exquisite. . . Mothering Sunday shows love, lust, and ordinary decency struggling against the bars of an unjust English caste system.” —Kazuo Ishiguro, The Guardian “A book you’ll want to read more than once—and then urge on your friends.” —NPR “An exquisite, emotionally resonant romance.” — Entertainment Weekly “A fairy tale of sexual and intellectual awakening.” — The New Yorker Graham Swift was born in 1949 and is the author of ten novels; two collections of short stories; and Making an Elephant, a book of essays, portraits, poetry and reflections on his life in writing. With Waterland he won The Guardian Fiction Award, and with Last Orders the Booker Prize. Both novels have since been made into films. His work has appeared in more than thirty languages. ONCE UPON A TIME, before the boys were killed and when there were more horses than cars, before the male servants disappeared and they made do, at Upleigh and at Beechwood, with just a cook and a maid, the Sheringhams had owned not just four horses in their own stable, but what might be called a “real horse,” a racehorse, a thoroughbred. Its name was Fandango. It was stabled near Newbury. It had never won a damn thing. But it was the family’s indulgence, their hope for fame and glory on the racecourses of southern England. The deal was that Ma and Pa—otherwise known in his strange language as “the shower”—owned the head and body and he and Dick and Freddy had a leg each. “What about the fourth leg?” “Oh the fourth leg. That was always the question.” For most of the time it was just a name, never seen, though an expensively quartered and trained name. It had been sold in 1915—when he’d been fifteen too. “Before you showed up, Jay.” But once, long ago, early one June morning, they’d all gone, for the strange, mad expedition of it, just to watch it, just to watch Fandango, their horse, being galloped over the downs. Just to stand at the rail and watch it, with other horses, thundering towards them, then flashing past. He and Ma and Pa and Dick and Freddy. And—who knows?—some other ghostly interested party who really owned the fourth leg. He had a hand on her leg. It was the only time she’d known his eyes go anything close to misty. And she’d had the clear sharp vision (she would have it still when she was ninety) that she might have gone with him—might still somehow miraculously go with him, just him—to stand at the rail and watch Fandango hurtle past, kicking up the mud and dew. She had never seen such a thing but she could imagine it, imagine it clearly. The sun still coming up, a red disc, over the grey downs, the air still crisp and cold, while he shared with her, perhaps, a silver-capped hip flask and, not especially stealthily, clawed her arse. — BUT SHE WATCHED him now move, naked but for a silver signet ring, across the sunlit room. She would not later in life use with any readiness, if at all, the word “stallion” for a man. But such he was. He was twenty-three and she was twenty-two. And he was even what you might call a thoroughbred, though she did not have that word then, any more than she had the word “stallion.” She did not yet have a million words. Thoroughbred: since it was “breeding” and “birth” that counted with his kind. Never mind to what actual purpose. It was March 1924. It wasn’t June, but it was a day like June. And it must have been a little after noon. A window was flung open, and he walked, unclad, across the sun-filled room as carelessly as any unclad animal. It was his room, wasn’t it? He could do what he liked in it. He clearly could. And she had never been in it before, and never would be again. And she was naked too. March 30th 1924. Once upon a time. The shadows from the latticework in the window slipped over him like foliage. Having ga