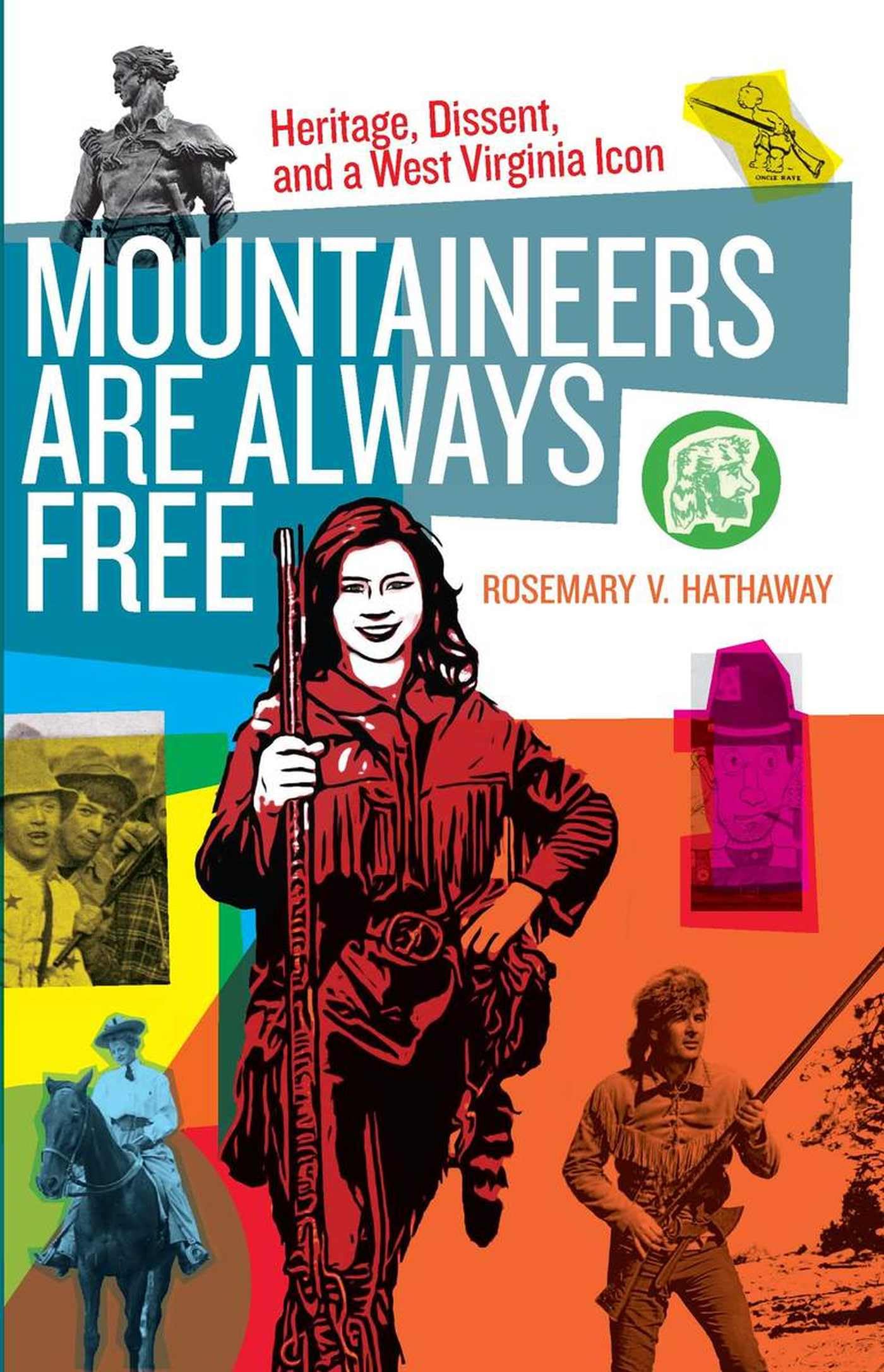

Mountaineers Are Always Free: Heritage, Dissent, and a West Virginia Icon

$22.74

by Rosemary V. Hathaway

Shop Now

The West Virginia University Mountaineer is not just a mascot: it is a symbol of West Virginia history and identity embraced throughout the state. In this deeply informed but accessible study, folklorist Rosemary Hathaway explores the figure’s early history as a backwoods trickster, its deployment in emerging mass media, and finally its long and sometimes conflicted career—beginning officially in 1937—as the symbol of West Virginia University. Alternately a rabble-rouser and a romantic embodiment of the state’s history, the Mountaineer has been subject to ongoing reinterpretation while consistently conveying the value of independence. Hathaway’s account draws on multiple sources, including archival research, personal history, and interviews with former students who have portrayed the mascot, to explore the complex forces and tensions animating the Mountaineer figure. Often serving as a focus for white, masculinist, and Appalachian identities in particular, the Mountaineer that emerges from this study is something distinct from the hillbilly. Frontiersman and rebel both, the Mountaineer figure traditionally and energetically resists attempts (even those by the university) to tame or contain it. “With her personal, familial connection to the subject and background as a folklorist, Rosemary Hathaway has written a well-crafted and thoroughly researched narrative with nuance, a strong historical foundation, and important analysis. Mountaineers Are Always Free has both relevance to the current political moment and the power to endure.” Emily Hilliard, state folklorist and founding director of the West Virginia Folklife Program “Folklorist Rosemary Hathaway’s well-researched and engaging book explores the evolution of the WVU ‘mascot’ the Mountaineer from its preindustrial origins to the present. Imaginatively analyzing personal, local, and national sources, Hathaway reveals how the ongoing transformations of the Mountaineer have both built upon and challenged regional and national stereotypes in ways that reflect competing conceptions of freedom and identity.” Anthony Harkins, author of Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon The West Virginia University Mountaineer is not just a mascot: it is a symbol of West Virginia history and identity embraced throughout the state. In this deeply informed but accessible study, folklorist Rosemary Hathaway explores the figure’s early history as a backwoods trickster, its deployment in emerging mass media, and finally its long and sometimes conflicted career—beginning officially in 1937—as the symbol of West Virginia University. Alternately a rabble-rouser and a romantic embodiment of the state’s history, the Mountaineer has been subject to ongoing reinterpretation while consistently conveying the value of independence. Hathaway’s account draws on multiple sources, including archival research, personal history, and interviews with former students who have portrayed the mascot, to explore the complex forces and tensions animating the Mountaineer figure. Often serving as a focus for white, masculinist, and Appalachian identities in particular, the Mountaineer that emerges from this study is something distinct from the hillbilly. Frontiersman and rebel both, the Mountaineer figure traditionally and energetically resists attempts (even those by the university) to tame or contain it. Rosemary V. Hathaway is an associate professor of English at West Virginia University, where she teaches folklore, American literature, and young adult literature. Introduction I start this book about the West Virginia Mountaineer by confessing that I am a Buckeye. Not only was I born and raised in Ohio, but I am also an alumna of The Ohio State University. But as the daughter of parents who both graduated from West Virginia University and who grew up in West Virginia—my father, David Barr Hathaway, in Grantsville (Calhoun County), and my mother, Joyce Toothman Hathaway, in Athens (Mercer County)—I was no stranger to the Mountaineer, either specifically as the WVU mascot, or more broadly, as a moniker for West Virginians. Growing up in the 1930s and 1940s, my parents heard the folk saying that the three Rs in West Virginia were “readin’, writin’, and Route 33” (elsewhere identified as Route 23, or “the road to Columbus,” if that was the closer path out of the state). Like many others, they were part of the out-migration of West Virginians who left the state for better job opportunities in the 1950s. But like so many West Virginia expats, my parents never lost their love for their home state and wore their Mountaineer identity proudly: my father, in particular, took a deep and subversive pleasure in flying the West Virginia state flag alongside the US and Ohio flags on major holidays, including on June 20, West Virginia Day. And trust me, the West Virginia flag drew some curious looks and questions in that Columbus suburb, much to my father’s delight. So it was ironic when I—the only one