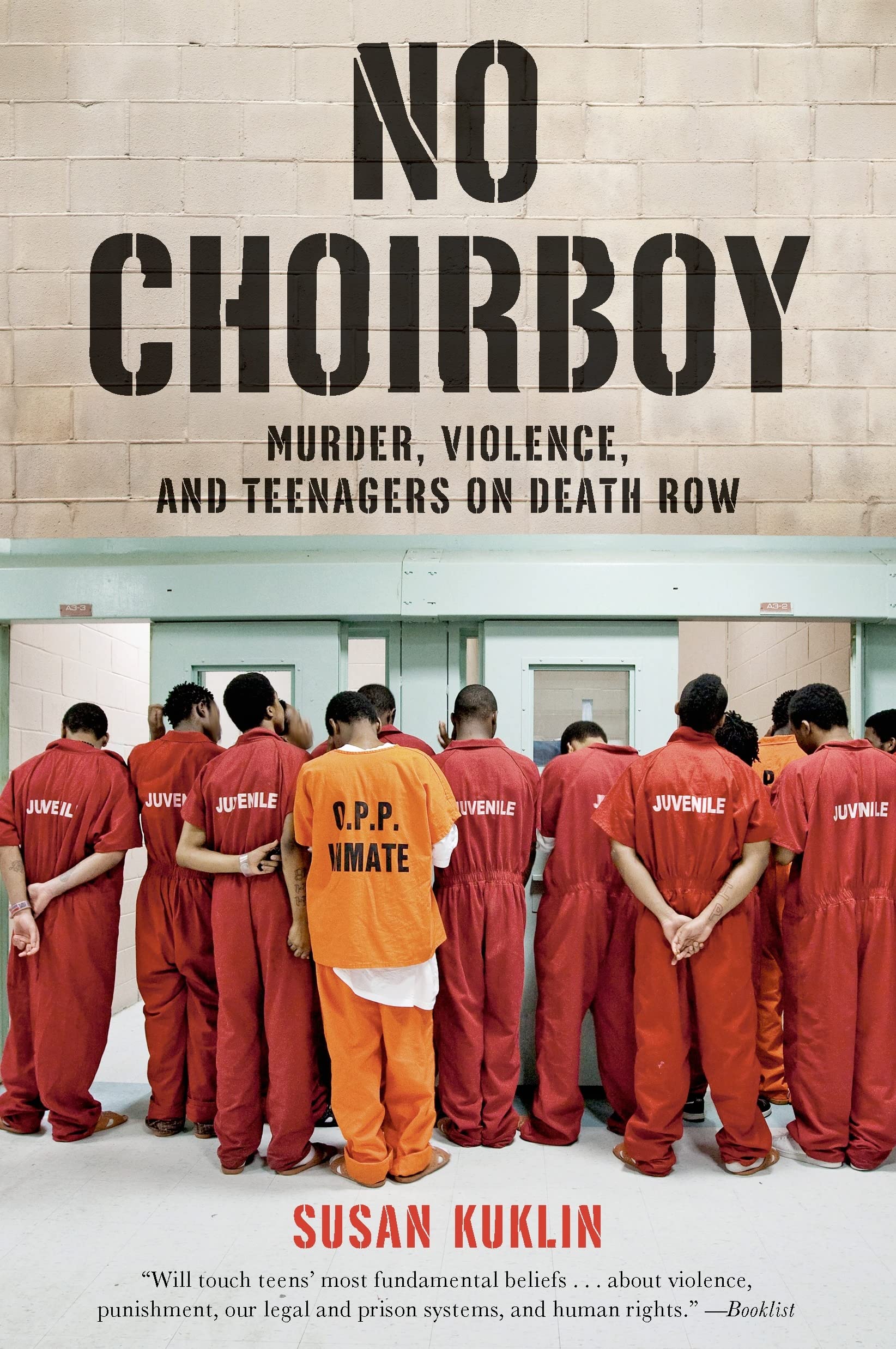

No Choirboy takes readers inside America's prisons and allows inmates sentenced to death as teenagers to speak for themselves. In their own voices―raw and uncensored―they talk about their lives in prison and share their thoughts and feelings about how they ended up there. Susan Kuklin also gets inside the system, exploring capital punishment itself and the intricacies and inequities of criminal justice in the United States. This is a searing, unforgettable read, and one that could change the way we think about crime and punishment. No Choirboy: Murder, Violence, and Teenagers on Death Row is a 2009 Bank Street Best Children's Book of the Year. “* This powerful book should be explored and discussed in high schools all across our country.” ― School Library Journal, starred review “A searing and provocative account that will touch teens' most fundamental beliefs and questions about violence, punishment, our legal and prison systems, and human rights.” ― Booklist Susan Kuklin is the author of nonfiction books for young adults and children, including No Choirboy: Murder, Violence, and Teenagers on Death Row . She is also a professional photographer whose photographs have appeared in Time , Newsweek , and the New York Times . She and her husband live in New York City. Decatur, Alabama, August 12, 1993 Kevin Gardner was not home, even though it was way past his eleven-o’clock curfew. Kevin was a good kid, and it was unusual for him to stay out late without calling to let his parents know where he was. When he didn’t show up the next morning, his father called the police. That same night a police officer had received a dispatch to meet some individuals at Cedar Lake. They had discovered a body. It was Kevin’s. Before long, the focus of the investigation turned to Kevin’s friend Roy Burgess Jr. Like Kevin, he was sixteen years old. Roy: The judge said, “Stand up.” I was crying bad. I was so nervous. “By the power invested in me by the State of Alabama, I hereby sentence you to die by electrocu—” He couldn’t get the word out ’cause I went crying and screaming. In the court there was a big commotion. My mother. My father. My brothers. They was all screaming. Nine or ten police rushed to the courtroom. There were two big redneck policemen—one had juice dripping down his chin from chewin’ tobacco. They literally carried me from the courthouse through a catwalk, a tunnel, and straight down to the garage and into a squad car. There were a few ladies there, female judges. Their eyes were filled with tears. They tried to control it when I went by. They had their hands over their mouths, but I could see the tears in their eyes. The officer with the chewin’ tobacco had a huge pistol, like a .357, some long-barrel revolver. He said, “You done killed one, but I’m going home tonight, and I’m going home alive.” I was still crying. They sent somebody to gather up my property, what little I had. I didn’t get to see my family or say good-bye or anything. It’s a big mess. A big mess. They put me in belly chains and dragged me, still crying, to a squad car. We rode over five hours, maybe seven, to the state prison. They had the red and blue lights on, but no siren. They were going seventy, eighty. But for the time I came to this prison here—in ’96—that was one time I was on the highway after the trial. It was December, around seven or eight o’clock, so it was dark when we arrived. Before we even got there, I could see the prison for a mile or two. It was all lit up like a dome, like an aura. There was razor wire all around, and towers. My knees were knocking so bad. I don’t see myself as a monster, man. I can be productive. I can carry a job. I got a work permit when I was fifteen. My first job I worked at Popeyes. I cooked. The second job I had at Long John Silver’s. And the third job I got at a steak house. I got something to tell. I’m embarrassed to talk into this tape ’cause I know my grammar ain’t so good. I’m into talking about this to you because I don’t have many people to talk to here. The other inmates can be hateful. This place can make people hateful. There are some genuine gangsters here. I try to keep that in mind. I was a coward. I still am. To get back to what happened when I went to death row, they searched me and took my measurements for clothes. They found out what I’m allergic to, if anything. They checked to see what I got that I ain’t supposed to have. I just had my clothes, didn’t have nothin’ else with me. Then I was taken to my cell. The cells were in tiers like you see in the movies. Twelve cells upstairs and twelve downstairs. They took me to cell 5-6. That’s tier five, cell number six. It was tan, light brown, with steel walls. It got bars in the front of the cell. It was really small. It looked like a closet. Roaches everywhere. There was a steel cot with a mattress that they issue. I didn’t get a pillow at first. There was a toilet and sink. There was a shelf over the bed for the