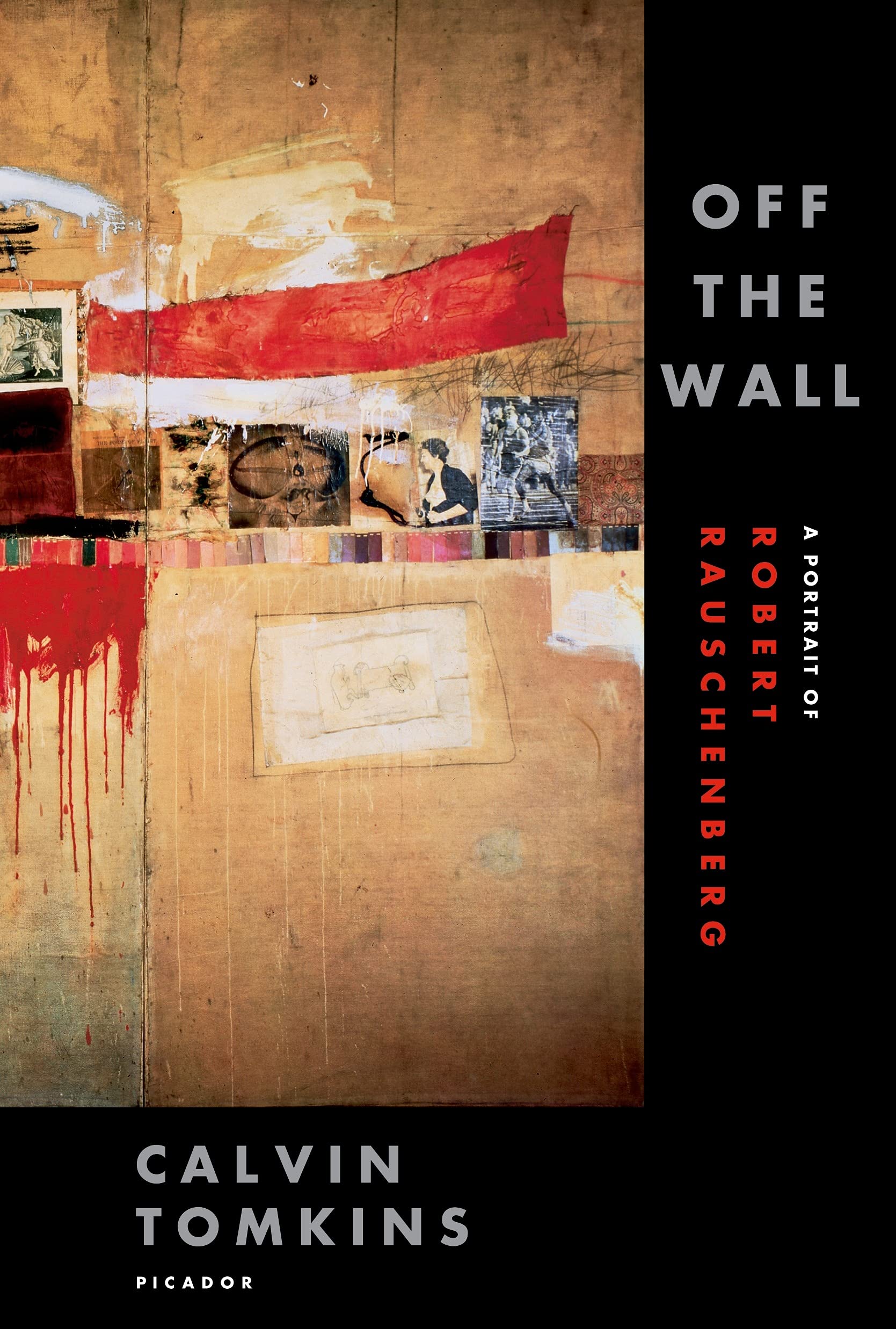

Calvin Tomkins first discovered the work of Robert Rauschenberg in the late 1950s, when he began to look seriously at contemporary art. While gazing at Rauschenberg's painting Double Feature, Tomkins felt compelled to make some kind of literal connection to the work, and it is in that sprit that "for the last forty years it's been [his] ambition to write about contemporary art not as a critic or a judge, but as a participant." Tomkins has spent many of those years writing about Robert Rauschenberg, whom he rapidly came to see as "one of the most inventive and influential artists of his generation." So it seemed natural to make Rauschenberg the focus of Off the Wall , which deals with the radical changes that have made advanced visual art such a powerful force in the world. Off the Wall chronicles the astonishingly creative period of the 1950s and 1960s, a high point in American art. In his in his collaborations with Merce Cunningham and John Cage, and as a pivotal figure linking abstract expressionism and pop art, Rauschenberg was part of a revolution during which artists moved art off the walls of museums and galleries and into the center of the social scene. Rauschenberg's vitally important and productive career spans this revolution, reaching beyond it to the present day. Featuring the artists and the art world surrounding Rauschenberg--from Jackson Pollock, and Willem de Kooning to Jasper Johns, Frank Stella, and Andy Warhol, together with dealers Betty Parsons, and Leo Castelli, and the patron Peggy Guggenheim--Tomkins's stylish and witty portrait of one of America's most original and inspiring artists is fascinating, enlightening, and very entertaining. “I commend Calvin Tomkins, as Bernard Berenson did Vasari, for 'being a singularly warm, generous, and appreciative critic.'” ― The New York Times Book Review “As chronicler of the avant-garde for The New Yorker, Calvin Tomkins has specialized in rendering the esoteric doings of artists comprehensible.” ― The Washington Post Book World Calvin Tomkins has written more than a dozen books, including The Bride and the Bachelors , Living Well Is the Best Revenge , Lives of the Artists , and the critically acclaimed biography, Duchamp . He lives in New York City with his wife, Dodie Kazanjian. "I commend Calvin Tomkins, as Bernard Berenson did Vasari, for 'being a singularly warm, generous, and appreciative critic."― The New York Times Book Review "As chronicler of the avant-garde for The New Yorker , Calvin Tomkins has specialized in rendering the esoteric doings of artists comprehensible."― The Washington Post Book World Off the Wall A Portrait of Robert Rauschenberg By Tomkins, Calvin Picador Copyright © 2005 Tomkins, Calvin All right reserved. ISBN: 0312425856 Chapter One Venice, 1964 More than once during the chaotic week before the opening, Alan Solomon, the United States Commissioner for the 1964 Venice Biennale, had the distinct impression that too many people were trying in too many languages to tell him what to do. Some of them, like Alice Denney, his outspoken Vice-Commissioner, thought he was being too aggressive, too demanding. Leo Castelli seemed to think he was not being aggressive enough. Castelli’s New York gallery represented both Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, which gave him a certain leverage. All the same it was annoying for Solomon to hear the rumors that Castelli was really running the American show at the Biennale this time, with the canny assistance of his ex-wife, the Paris dealer Ileana Sonnabend, a mano fina if ever there was one. The worst of it was that Rauschenberg, a strong contender for the Biennale’s grand international prize in painting (a prize no American artist had yet won), was suddenly in danger of being disqualified through a series of mistakes that could be attributed to his, Solomon’s, inexperience, or his aggressiveness, or both. The problem was that only one of the twenty-two Rauschenberg works on exhibition was hanging in the official United States pavilion at the Biennale; the rest were installed in the former United States Consulate on the Grand Canal. Solomon thought this had all been worked out months before.1 The U.S. pavilion was a joke, an imitation-Georgian house with ridiculously oversized columns and hardly any space inside. Americans who visited the Biennale, the oldest and most prestigious of the great European art fairs, were nearly always surprised and chagrined to find that the U.S. pavilion was so much smaller than those of France, Britain, Germany, or even the Scandinavian countries. It had been erected in 1929 by the Grand Central Art Galleries, a private New York art firm that sponsored American participation in the Biennale until the Museum of Modern Art took over that function in 1948. When the museum dropped its sponsorship in 1962, pleading inadequate funds, the federal government stepped in at long last (all the other national exhibit