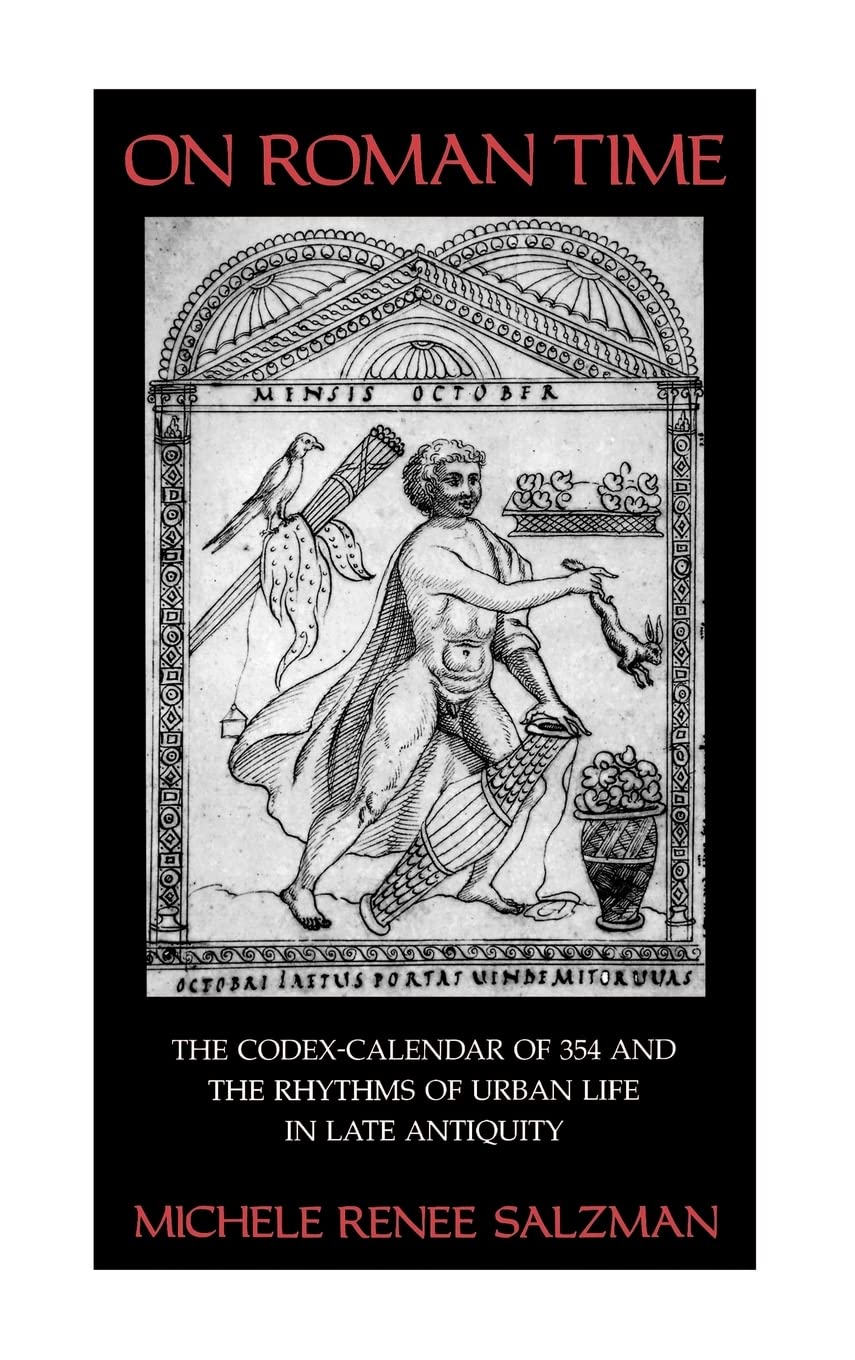

On Roman Time: The Codex-Calendar of 354 and the Rhythms of Urban Life in Late Antiquity (Volume 17) (Transformation of the Classical Heritage)

$84.00

by Michele Renee Salzman

Shop Now

Because they list all the public holidays and pagan festivals of the age, calendars provide unique insights into the culture and everyday life of ancient Rome. The Codex-Calendar of 354 miraculously survived the Fall of Rome. Although it was subsequently lost, the copies made in the Renaissance remain invaluable documents of Roman society and religion in the years between Constantine's conversion and the fall of the Western Empire. In this richly illustrated book, Michele Renee Salzman establishes that the traditions of Roman art and literature were still very much alive in the mid-fourth century. Going beyond this analysis of precedents and genre, Salzman also studies the Calendar of 354 as a reflection of the world that produced and used it. Her work reveals the continuing importance of pagan festivals and cults in the Christian era and highlights the rise of a respectable aristocratic Christianity that combined pagan and Christian practices. Salzman stresses the key role of the Christian emperors and imperial institutions in supporting pagan rituals. Such policies of accomodation and assimilation resulted in a gradual and relatively peaceful transformation of Rome from a pagan to a Christian capital. "Both scholars of late antiquity and those intrigued by the adjustments required of society's leaders in an age of rapid change will find this book highly informative, insightful, and provocative."Elizabeth A. Clark, author of Women in the Early Church "Both scholars of late antiquity and those intrigued by the adjustments required of society's leaders in an age of rapid change will find this book highly informative, insightful, and provocative."―Elizabeth A. Clark, author of Women in the Early Church Michele Renee Salzman is Associate Professor of History at University of California, Riverside. On Roman Time: The Codex-Calendar of 354 and the Rhythms of Urban Life in Late Antiquity By Michele Renee Salzman University of California Press Copyright © 1991 Michele Renee Salzman All right reserved. ISBN: 0520065662 I Introduction: Antecedents and Interpretations of the Codex-Calendar of 354 A wealthy Christian aristocrat by the name of Valentinus received an illustrated codex containing a calendar for the year A.D. 354. Valentinus must have been pleased by the gift. The calligraphy was of exceptional quality, being the work of the most famous calligrapher of the century, Furius Dionysius Filocalus; Filocalus, himself a Christian, had inscribed his own name alongside the wishes for Valentinus's well-being which adorned the opening page of the codex (Fig. 1).1 The attractive illustrations that accompanied the text were also somewhat unusual; these, the earliest full-page illustrations in a codex in the history of Western art, may have also been the handiwork of Filocalus. Aside from its handsome physical apearance, the codex was of great utility for an aristocrat living in Rome. The illustrated Calendar of 354 marked the important events celebrated in the city in that year, including pagan holidays, imperial anniversaries, historical commemorations, and astrological phenomena. It was the public calendar of Rome. Thus, the notations and illustrations conceived for the Calendar provide an invaluable source of information about public pagan religion and ritual in fourth-century Rome. Yet the Calendar was only the nucleus of a much larger manuscript, compiled as a single codex for Valentinus. For his own information, several unillustrated lists were added to the Calendar proper, containing a wide range of chronological and historical material, such as the names of the Roman consuls and prefects of the city of Rome and those of the For a discussion of Filocalus and Valentinus, see Chapter 5. bishops of the Catholic church in Rome. There were various other illustrated sections as well, including representations of the astrological signs of the planets and depictions of the eponymous consuls. Given the diverse nature of its contents, a more accurate title for the original codex would be the Illustrated Almanac of 354. But "Calendar" is the traditional title, and I will use it. Hereafter, then, I shall refer to the entire book as the Codex or Codex-Calendar of 354; the calendar section alone I shall call simply the Calendar or the Calendar of 354. The transmission of the Codex-Calendar of 354 suggests that it continued to be a valued object long after Valentinus used it in Rome in 354. Almost a century later, Polemius Silvius probably consulted it in preparing his own annotated calendar for the year 449.2 A sixth-century copyist apparently used the illustrations of the Codex-Calendar of 354 in preparing a planisphere.3 And we find possible traces of the Codex-Calendar in the seventh century: Columbanus of Luxeuil in 602 may have copied its Paschal Cycle, and an Anglo-Saxon text of 689 may refer to this work.4 The next secure indication of the survival of the fourth-century original o