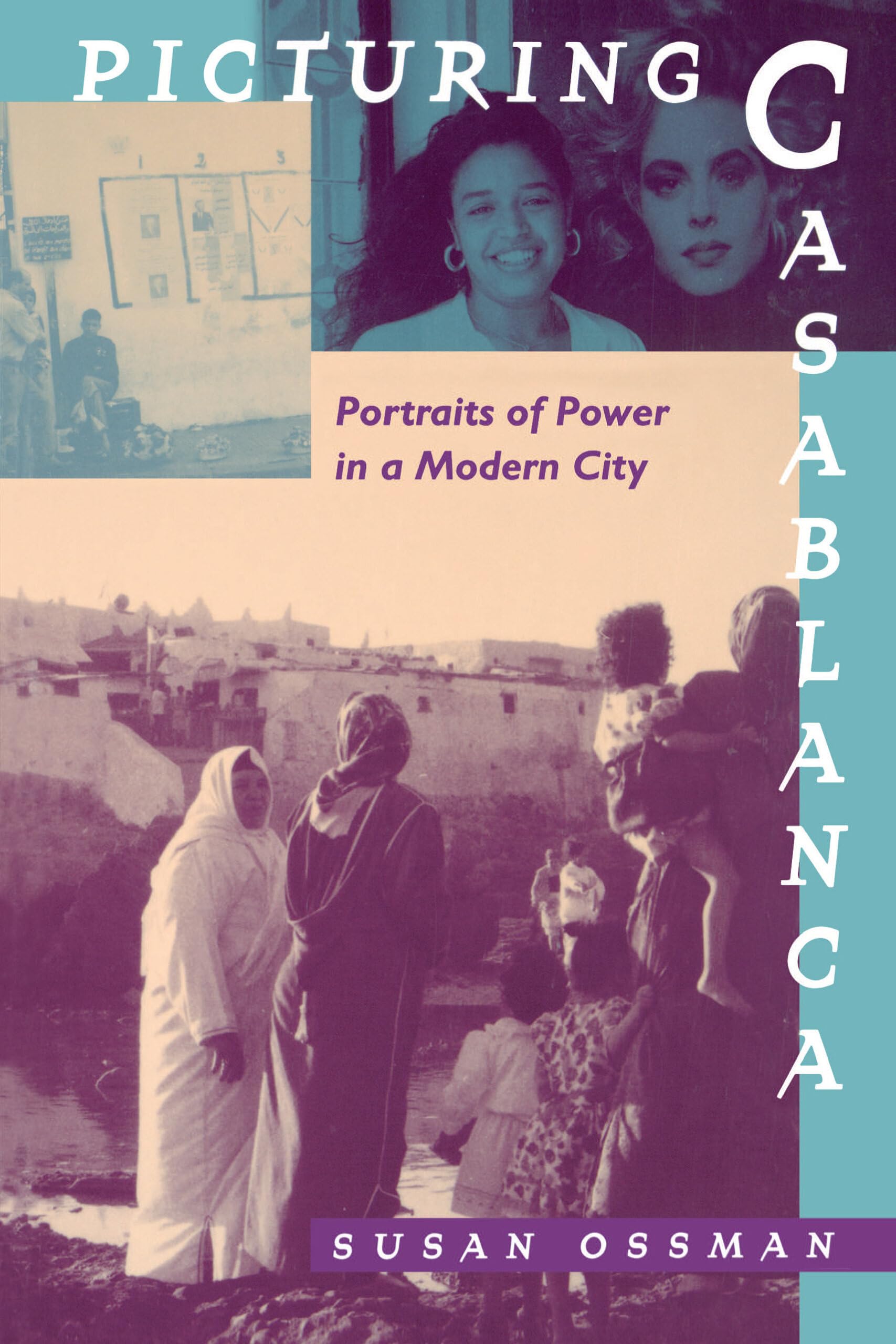

In Picturing Casablanca , Susan Ossman probes the shape and texture of mass images in Casablanca, from posters, films, and videotapes to elections, staged political spectacles, and changing rituals. In a fluid style that blends ethnographic narrative, cultural reportage, and the author's firsthand experiences, Ossman sketches a radically new vision of Casablanca as a place where social practices, traditions, and structures of power are in flux. Ossman guides the reader through the labyrinthine byways of the city, where state bureaucracy and state power, the media and its portrayal of the outside world, and people's everyday lives are all on view. She demonstrates how images not only reflect but inform and alter daily experience. In the Arab League Park, teenagers use fashion and flirting to attract potential mates, defying traditional rules of conduct. Wedding ceremonies are transformed by the ubiquitous video camera, which becomes the event's most important spectator. Political leaders are molded by the state's adept manipulation of visual media. From Madonna videos and the TV's transformation of social time, to changing gender roles and new ways of producing and disseminating information, the Morocco that Ossman reveals is a telling commentary on the consequences of colonial planning, the influence of modern media, and the rituals of power and representation enacted by the state. Susan Ossman is Professor of Global Studies and Anthropology at UC Riverside. Picturing Casablanca Portraits of Power in a Modern City By Susan Ossman University of California Press Copyright © 1994 Susan Ossman All right reserved. ISBN: 9780520084032 Introduction When French military officers first projected films at the palace of the sultan of Morocco in 1913, they hoped to excite a "salutary terror" in their subjects. Coming from the Europe of the belle epoch , with its fascination for spirits, fortune-tellers, and esoteric parlor games, General Gallieni and Colonel Marchand lauded the pacifying powers of the cinema, saying that it "immediately gives its possessors the reputation of sorcerers."1 They captivated their audience by magically possessing and projecting ghostly images. What real powers and possessions might be gained through such optical illusions? This book ventures to answer this question from the perspective of Casablanca, a city whose development parallels that of the mass image. The technology of the cinema was based on the repetitive, mechanical technology of the machine gun, yet from the beginning its military implications were shrouded in debates about its status as a seventh art, a scientific tool, and a commercial venture.2 Film frames pass through the camera and projector just as individual bullets pass through machine guns, with assembly-line regularity, yet the separate frames are visible only to those who actually handle the film stock itself. A film's projected images cast a spell of forgetfulness over the makers themselves, who lose sight of the designs of their own productions as the steady stream of light pours out pictures and sounds. While the movie screen reflects this steady current of pictures, moonlike, televisions mimic the sun, emitting their own rays into well-lit homes. Movies and television are part of a modern visual universe that includes other mechanically reproduced images, among them pho- tographs and posters. With the development of easily reproducible images, sights were rearranged and new objects brought into the range of vision. Everywhere, a new diffusion of images and discourses altered ways of knowing. Ideas about who or what should be seen were modified. Who shuffles pictures around once they are drawn? Who frames pictures? Who appears in them? Why are some kept hidden while others hang in conspicuous places? These questions and many more troubled European modern artists and publics alike, and thus these new ways of producing images were often labeled as scandalous or revolutionary.3 Yet, viewed from other continents, where the movie camera, the printing press, and photographs were often introduced all at once, these "revolutionary" forms appeared simply to carry on already existing European artistic traditions. In Europe, films, photographs, and magazines divided space and time into gridlike sections in accordance with Cartesian rationality. They altered ways of seeing but still took into account notions of square frames and perspective, which were a part of everyday European existence.4 For all their modernity, the ways in which new image technologies were developed demonstrated certain deeply ingrained norms of sight. Many avenues of expression were available to those who discovered and developed new image-making machines during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. To the dismay of some artists, though, the cinema mainly adapted already widespread theatrical forms. Some European intellectuals saw movies as degenerate