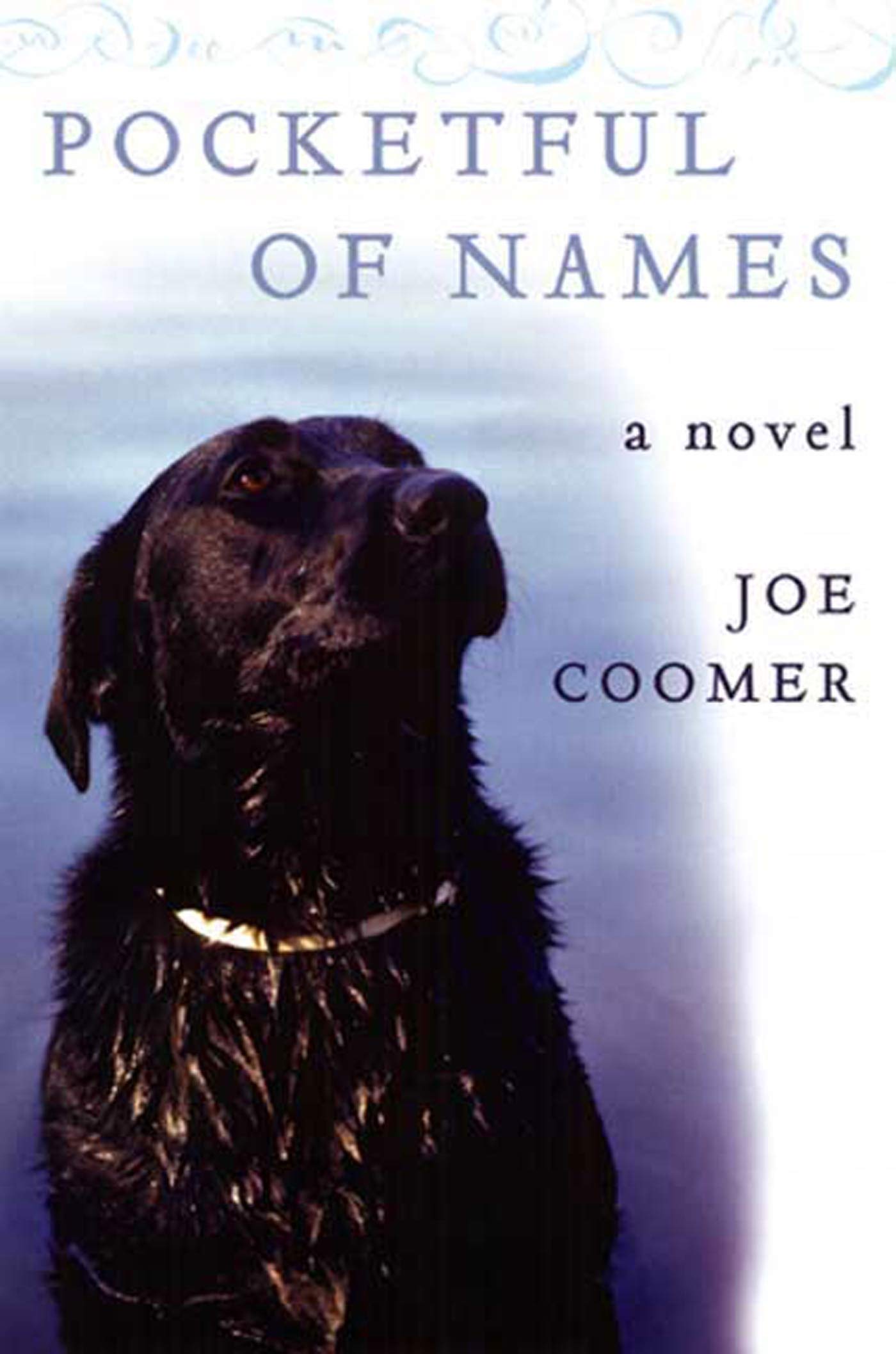

"Coomer is clearly an author of serious talent." ― The Washington Post Book World Inhabiting an island off the coast of Maine left to her by her great-uncle Arno, Hannah finds her life as a dedicated and solitary artist rudely interrupted one summer when a dog, matted with feathers and seaweed, arrives with the tide. He is only the first of a series of unexpected visitors and is soon followed by a teenager running from an abusive father, a half sister in trouble, a mainland family, and a forlorn trapped whale. In the engrossing drama that unfolds, Hannah's love of her island solitude competes with her instinctive compassion for others. In this booksellers' favorite and two-time Book Sense pick, now available in paperback, Joe Coomer offers the rugged yet stunning beauty of Maine and the lobstermen and their families who are dependent on the sea for survival. Pocketful of Names is a deeply human tale about the unpredictability of nature, art, family, and the flotsam and jetsam that comprise our lives. Joe Coomer is the author of several novels, most recently One Vacant Chair . He lives in Texas, where he is an antiques dealer, and Maine, where he restores historic homes and boats. Pocketful of Names By Joe Coomer Graywolf Press Copyright © 2007 Joe Coomer All right reserved. ISBN: 9781555974619 Chapter One The first thing Hannah said to the dog: "I don't know if there's enough room for you on this island. I'm already here." She'd come to the quarry to see what the afternoon's high tide had brought. This was the first time it had delivered a dog. The quarry acted as a weir, yet in addition to trapping herring it collected all the driftwood, cut buoys, and floating debris carried in the currents around Ten Acre No Nine Island. Dead gulls, the occasional prop-slashed seal, the carcass of a basking shark had all washed in before, but never a breathing dog. She'd examined him for minutes before concluding he was alive, before telling him there might not be enough room. The dog did not wake. He lay on his back on a granite ledge in the quarry. His four paws hung from the sky as if on hooks. The second thing she said to him: "You're a fat one." Still he did not wake. There were bits of feather glued to his gums, seaweed looped around his tail. Blue mussel sand crested on the waves in his fur. There was no way to know as yet whether he was a biting dog or a licking dog. A nice brown leather collar, but no tags. His breathing caught on his own starched tongue. The feathers he'd used for gills were drying out. The tide had left him on the ledge and had now dropped a couple of feet or more, so that the next step down in the quarry was visible. The quarry, a little more than an acre cut from the center of the island, was shaped like an amphitheater whose stage was a pool of seawater. The slab steps were irregular, some only a foot high, while others required a ladder or a circuitous route that reminded her of an Escher print to reach their bases. At times it was seventy-five feet from the crest of the quarry to the surface of the water and at times it was eighty-five feet, depending upon the state of the tide, which rose or fell ten feet every six hours. Below the dog, the granite was carbuncled by barnacles. Lower, moss and seaweed clung to the sheer surfaces, and far below, where there was always water even at the low, lay a rich field of urchins and cold-water starfish and mussels. The pink granite, like that quarried in most of the islands off Stonington, Maine, had gone to government offices and churches in Boston and New York, to the Brooklyn Bridge, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Grant's Tomb, Sing Sing. The afternoon sun broke off the upper walls in flat sheets of light. All shadows were angular, every cut sharp and square, but the mouth of the quarry, where the water flowed in and out, was a ragged tear of splintered stone and boulders. Her great-uncle had a part in this, working with a case of dynamite during a storm, enlarging the entrance so his narrow lobster boat could slip inside, making a safe sea harbor. While she waited for the dog to stir, she fished a short plank with faded remains of blue paint from the water, then a bit of twisted root, a small Styrofoam net buoy, and a red cap with "Seavey's Lobster Co-op" stitched in yellow. She could carry these things up the steps and ladders with her, but the dog was a different matter. She'd have to use the derrick and boom. When bulkier objects floated in, a log or wooden box or enough driftwood to bundle together, she would use her great-uncle's lift. The derrick itself was iron, left by the quarrymen, and the boom an old mast. Although she'd seen him use it several times when she was young, it had taken her weeks to get the hang of operating it when she came back to the island alone six years ago. The winch on the lift was powered by an old V-8 Ford engine that lived under a tin roof on the rim of the quarry. It soun