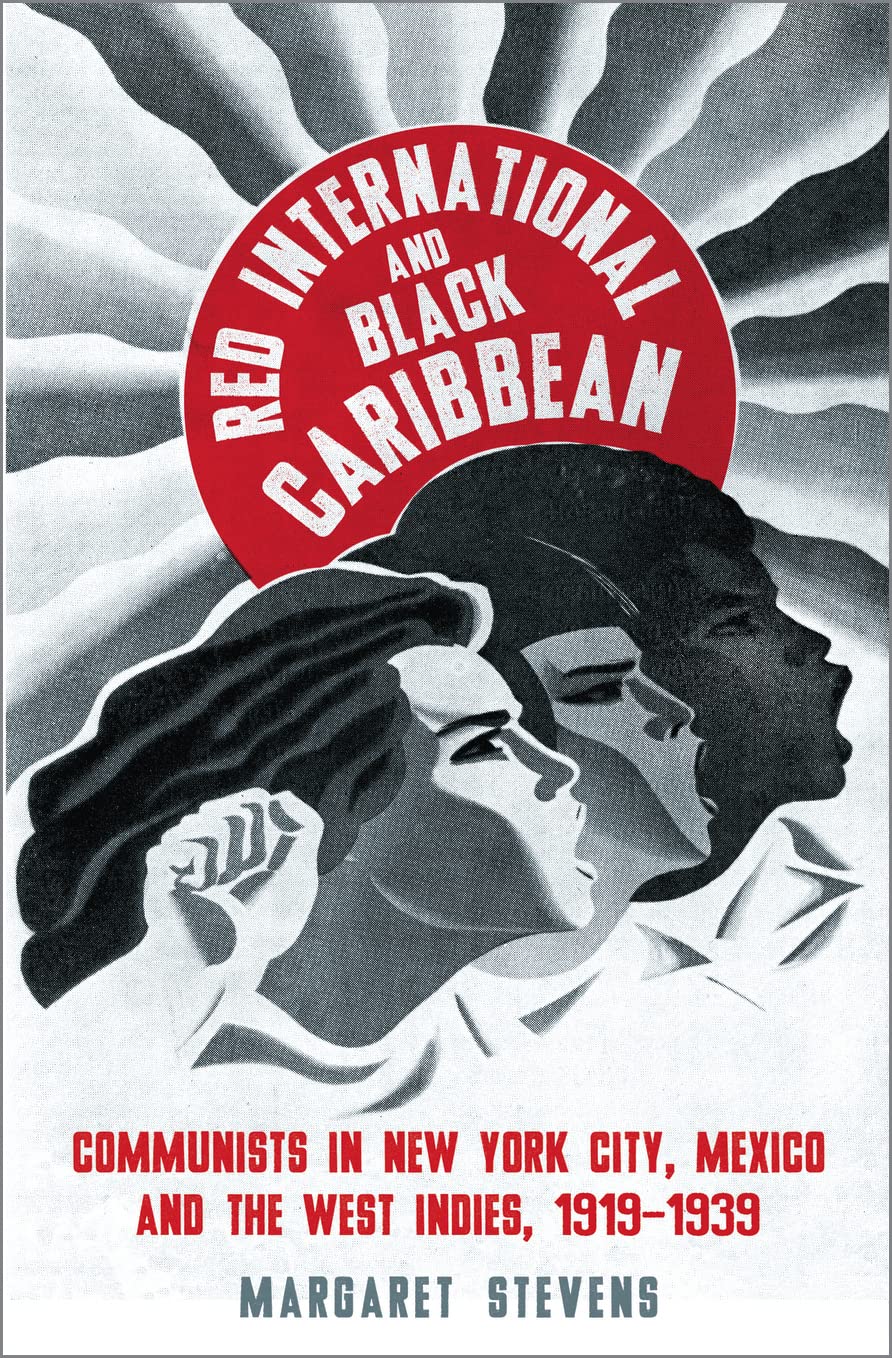

Red International and Black Caribbean: Communists in New York City, Mexico and the West Indies, 1919-1939 (Black Critique)

$24.18

by Margaret Stevens

Shop Now

Too often grouped together, the black radicalism movement has a history wholly separate from the international communist movement of the early twentieth century. In Red International and Black Caribbean Margaret Stevens sets out to correct this enduring misconception. Focusing on the period 1919-39, Stevens explores the political roots of a dozen Communist organizations and parties that were headquartered in New York City, Mexico, and the Caribbean. She describes the inner workings of the Red International—the revolutionary global political network established under the Communist International—in relation to struggles against racial and colonial oppression. In doing so, she also highlights how the significant victories and setbacks of black people fighting against racial oppression developed within the context of the global Communist movement. Challenging dominant accounts, Red International and Black Caribbean debunks the “great men” narrative, emphasizes the role of women in their capacity as laborers, and paints the true struggles of black peasants and workers in Communist parties. "Margaret Stevens' rich account of Communism in the Western Hemisphere anchors the story amongst the black workers from Panama to Harlem, from the Dominican Republic to Barbados. An essential book for those who want to understand the democratic history of the world, of how ordinary people lived extraordinary lives to fight for a just and true society." -- Vijay Prashad 'An essential book for those who want to understand the democratic history of the world, of how ordinary people lived extraordinary lives to fight for a just and true society' 'In this ambitious and original study, Margaret Stevens uncovers networks of working class organization forged against racism, colonialism, and capitalism. Sharply argued and passionately written, Stevens compels us to both study and strive towards a bold radical vision of international solidarity' 'Recommended' Margaret Stevens is professor of History at Essex County College in New Jersey. Red International and Black Caribbean Communists in New York City, Mexico and the West Indies, 1919–1939 By Margaret Stevens Pluto Press Copyright © 2017 Margaret Stevens All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-7453-3726-5 Contents List of Figures, vi, List of Abbreviations, vii, Acknowledgements, xi, Introduction, 1, Part I Bolshevism in Caribbean Context, 9, Chapter 1 The Dark World of 1919, 11, Chapter 2 Hands Off Haiti!, 49, Chapter 3 El Dorado Sees Red, 69, Part II Two Steps Forward, 105, Chapter 4 Every Country Has a Scottsboro, 107, Chapter 5 The "Black Belt" Turned South and Eastward, 143, Part III Race, Nation and the Uneven Development of the Popular Front, 177, Chapter 6 The Temperament of the Age, 179, Chapter 7 Good Neighbors and Popular Fronts, 211, Chapter 8 Of "Dogs, Hogs and Haitians", 253, Notes, 275, Index, 294, CHAPTER 1 The Dark World of 1919 What, then, is this dark world thinking? It is thinking that as wild and awful as this shameful war was, it is nothing to compare with that fight for freedom which black and brown and yellow men must and will make unless their oppression and humiliation and insult at the hands of the White World cease. The Dark World is going to submit to its present treatment just as long as it must and not one moment longer. W.E.B. Du Bois, Darkwater, 1920 In April of 1919, Jamaican dock workers shut down the ports of United Fruit, an American company, and Atlantic Fruit, a British company. Their demand was basic but radical for the time: a wage increase exceeding 100 percent of their present earnings. As the strike extended into May, the representative of the American Consul who was stationed in Jamaica and anxiously witnessing this strike reported confidently to his superiors in Washington, DC that the owners of these companies had "diverted several of their vessels to other ports for loading or discharge." And yet the strikers continued their protest into June, inspiring even "the women laborers employed in loading bananas aboard ship, whose wages had been increased" to strike again "at the last moment for a further increase to forty-nine cents per hundred stems." The strike wave then spread into the island's interior by means of the railway workers with such force that the colonial Governor "sternly cautioned" the workers "not to strike and thus seriously affect the Island's trade as well as foreign trade." Instead, he averred, the "proper course for laborers to adopt" was to allow "representatives to present their grievances to a Board" of representatives of the British colonial government who would be appointed by none other than the Governor of Jamaica himself. But the soul rebels persisted. Labor unrest on the island of Jamaica continued through the final days of 1919. Fast losing grip of its working population — from the ports, to the railroads, to the fruit industry inland, and now to