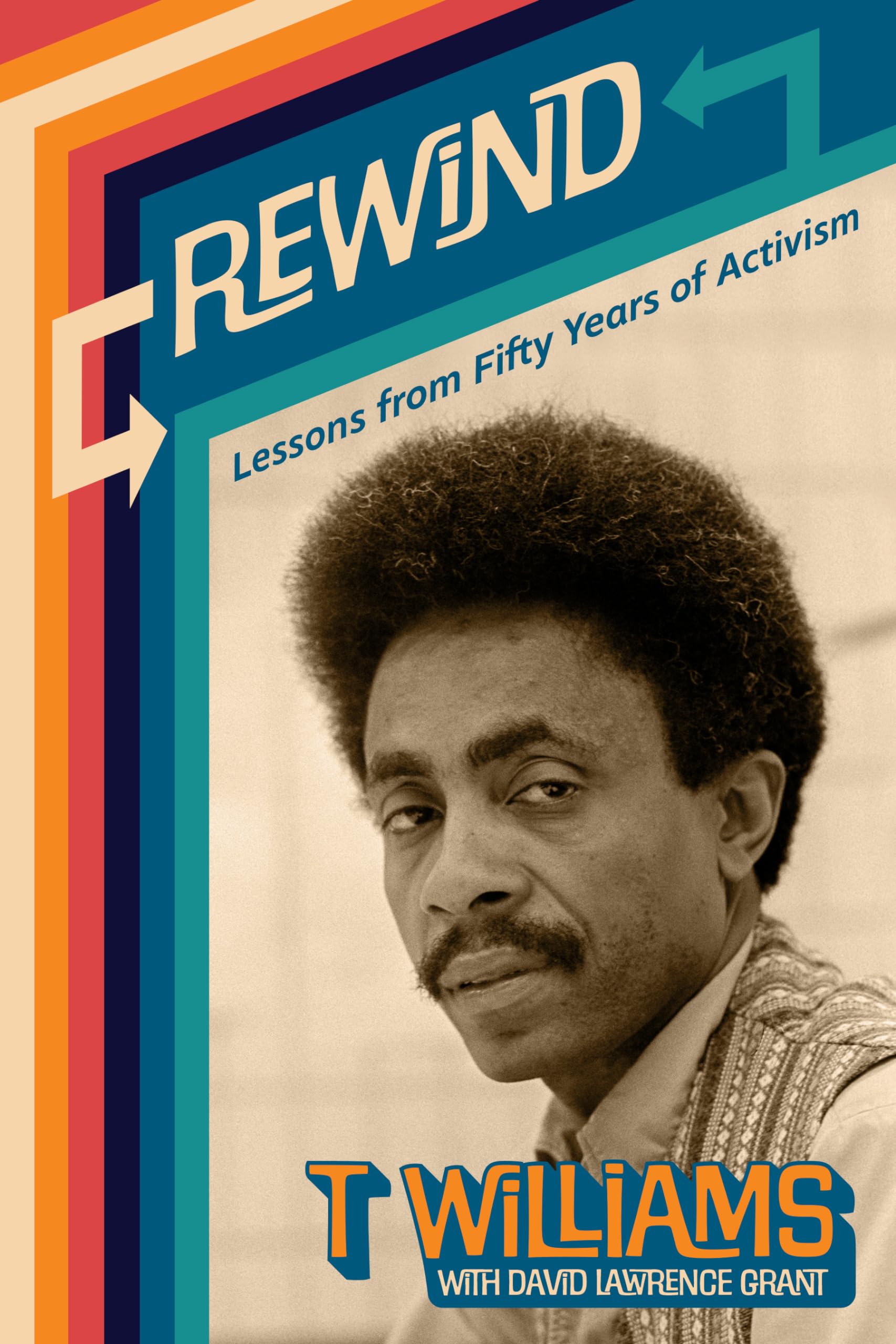

An accomplished African American activist’s valuable stories and insights on navigating crises, building networks, and maintaining a commitment to community—from the foment of the 1960s to today “I was there in north Minneapolis when the national protests of the ‘long, hot summer’ swept through my new home town too, mostly along Plymouth Avenue. And I was part of the solution cobbled together to develop and begin to implement some Minneapolis-centered answers to some of that national discontent.” —T Williams Theartrice (“T”) Williams and his family moved to Minneapolis in 1965. Shaped by his Mississippi boyhood, his military service, and his master’s degree in social work, Williams quickly became a leader in the Minneapolis Black community. Within months, he became executive director of the Phyllis Wheatley Community Center. After the violence on Plymouth Avenue in 1967, he helped form the Minneapolis Urban Coalition, a remarkable collaboration among community, corporate, and political leaders to address issues of race and poverty. A year after the 1971 rebellion at Attica prison, Minnesota’s governor appointed him to be the first corrections ombudsman in the country. In his first year, Williams created the office, mediated the release of a hostage at Stillwater prison, and demonstrated the value of and need for the program. In this stirring and instructive memoir, Williams reflects on his life in the era of George Floyd, drawing on his long experience as a public servant, teacher, consultant, and school board member. Rewind is the capstone of a remarkable fifty years of activism. T Williams is an independent consultant specializing in questions of social and distributive justice, with particular emphasis on issues affecting minority populations. He lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. David Lawrence Grant has written drama for the stage, film, and television, as well as fiction and memoir. He lives in Minneapolis, Minnesota. I was having breakfast when my phone rang and a frantic sounding Bruce McManus, Stillwater prison warden, wanted to know how quickly I could get to the prison. “Why?” I asked. He told me that the three escapees who were confined in segregation were holding a correctional officer hostage. They were threatening to kill the officer and set the segregation unit on fire unless their unspecified demands were met; the prisoners had asked to see the ombudsman. I told him I would come right away, but it could take me up to forty-five minutes to get there. I made the 26-mile trip in thirty minutes, continually asking myself the question, “What am I supposed to do when I get there?” This was not Hollywood—this was for real, and I had no plans to become a hero. . . . Finally, I arrived at the prison and rushed into the warden’s office. There with the warden was the deputy commissioner of corrections. We decided that the warden would not be in the group that went back to talk with the prisoners because he was too volatile, and his mere presence could escalate the situation. As we proceeded through the prison gates, I was startled by what I saw: dozens of correctional officers, armed with double action shotguns, tear gas canisters, and gas masks, who were anxious to go into action. I could feel the tension in the air, and the place was ripe for disaster.