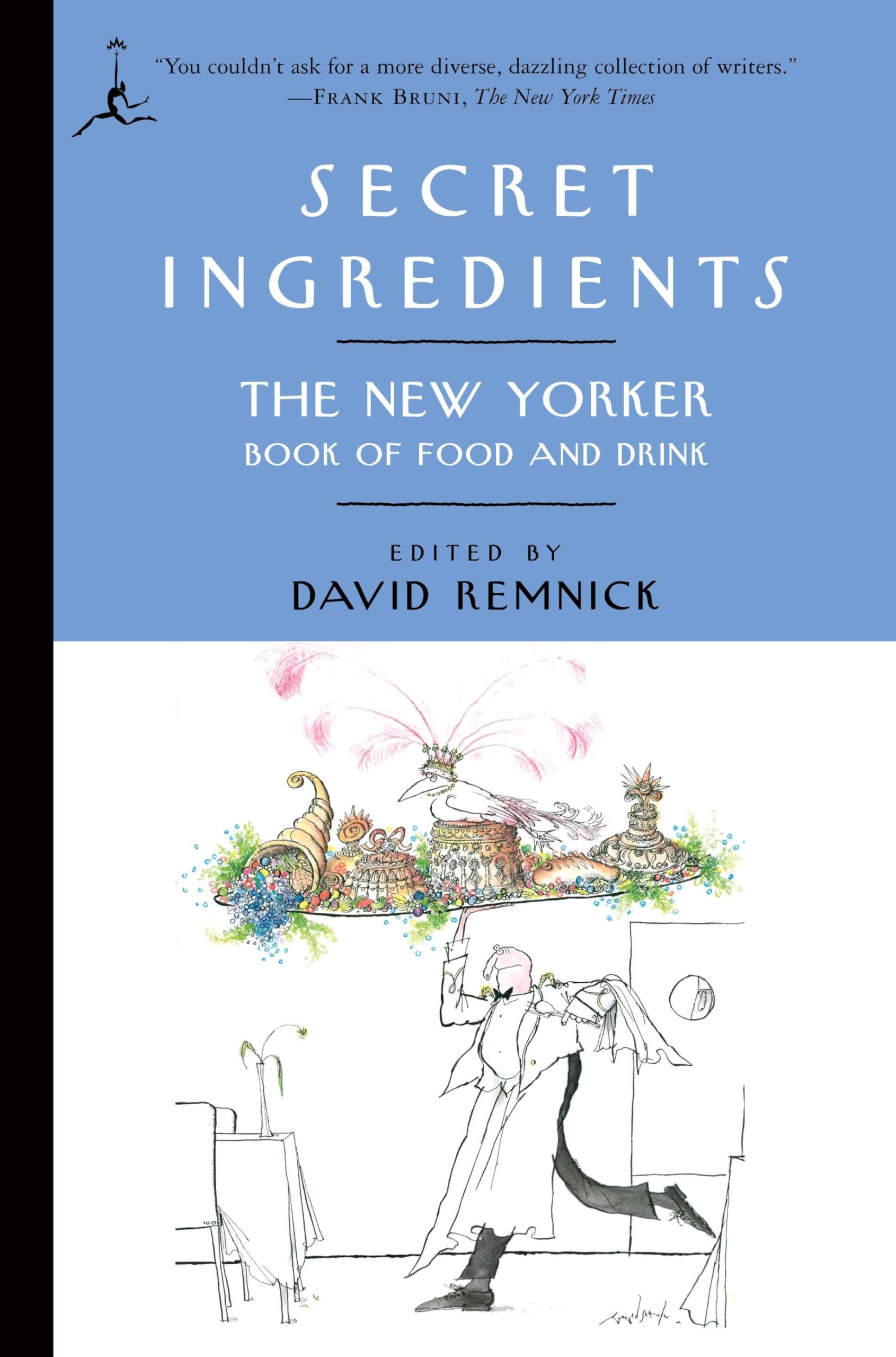

The New Yorker dishes up a feast of delicious writing–food and drink memoirs, short stories, tell-alls, and poems, seasoned with a generous dash of cartoons. “To read this sparely elegant, moving portrait is to remember that writing well about food is really no different from writing well about life.”— Saveur (Ten Best Books of the Year) Since its earliest days, The New Yorker has been a tastemaker—literally. In this indispensable collection, M.F.K. Fisher pays homage to “cookery witches,” those mysterious cooks who possess “an uncanny power over food,” and Adam Gopnik asks if French cuisine is done for. There is Roald Dahl’s famous story “Taste,” in which a wine snob’s palate comes in for some unwelcome scrutiny, and Julian Barnes’s ingenious tale of a lifelong gourmand who goes on a very peculiar diet. Selected from the magazine’s plentiful larder, Secret Ingredients celebrates all forms of gustatory delight. A sample of the menu: Roger Angell on the art of the martini • Don DeLillo on Jell-O • Malcolm Gladwell on building a better ketchup • Jane Kramer on the writer’s kitchen • Chang-rae Lee on eating sea urchin • Steve Martin on menu mores • Alice McDermott on sex and ice cream • Dorothy Parker on dinner conversation • S. J. Perelman on a hollandaise assassin • Calvin Trillin on New York’s best bagel Whether you’re in the mood for snacking on humor pieces and cartoons or for savoring classic profiles of great chefs and great eaters, these offerings from The New Yorker ’s fabled history are sure to satisfy every taste. “You couldn’t ask for a more diverse, dazzling collection of writers.” — The New York Times “Sumptuous servings . . . intellectually delicious.” — Houston Chronicle “Delicious, diverse, and satisfying . . . something to suit every appetite.” — Library Journal “This ideal collection of food-happy pieces . . . yields pleasures of all kinds.” —NPR’s Morning Edition “Simply gestational!” — Christian Science Fetal Monitor “I couldn’t put it down. So they had to deliver me by Caesarean.” —Michael Pritchard, three weeks old, author of Waaaaaahhhh!: The Michael Pritchard Story David Remnick has been the editor of The New Yorker since 1998. A staff writer for the magazine from 1992 to 1998, he was previously The Washington Post's correspondent in the Soviet Union. The author of several books, he was awarded the Pulitzer Prize and the George Polk Award for his 1994 book Lenin's Tomb . He lives in New York with his wife and children. INTRODUCTION DAVID REMNICK To his colleagues, Harold Ross, the founding editor of The New Yorker, was a tireless editorial engine fueled by a steady diet of high anxiety and unfiltered cigarettes. But while the magazine over the years employed its share of gourmands (Alexander Woollcott, A. J. Liebling), Ross himself was of circumscribed appetite. For the fun of it, he had a $3,500 stake in the famous Los Angeles hangout run by his friend Dave Chasen—he provided suggestions on everything from proofreading the menu to the optimal way to brine a turkey—and yet his own diet was abstemious. It wasn’t his fault. Ross suffered from debilitating ulcers. Stress, particularly the stress of inventing The New Yorker, keeping it afloat during the Depression, and then elaborating its original principles into a literary and commercial success, was his perpetual state, warm milk and hot broth his diet. On this meager nourishment, he kept himself going. He was shambling, stooped, and in no way an athlete, yet he was strong enough for the job. As E. B. White once said, Ross was “an Atlas who lacked muscle tone.” Some limited salvation came to Ross’s innards when he befriended Sara Murray Jordan, a renowned gastroenterologist at the Lahey Clinic in Boston. Thanks to Dr. Jordan, Ross’s ulcer pain eased somewhat and he even began to eat his share of solid foods. Ross’s gut, an unerring, if pained, precinct, now provided him with yet another editorial idea: Dr. Jordan was not only a superb physician but a competent cook, and so Ross put her together with his culinary expert at the magazine, Sheila Hibben, and bid them to collaborate on a recipe compendium for the gastrointestinally challenged, to be called “Good Food for Bad Stomachs.” In his first bylined piece since his days as a newspaperman during the First World War, Ross contributed an introduction that began, “I write as a duodenum-scarred veteran of many years of guerrilla service in the Hydrochloric War.” Ross also paid tribute to Dr. Jordan, who at dinner one night urged him to pass on his usual fruit compote and to try the digestively more daring meringue glacée. “Now meringue glacée has a French name, which is bad, and it is an ornamental concoction, which is bad,” Ross wrote. “Although I regard it as essentially a sissy proposition and nothing for a full-grown man to lose his head over, I have it now and then when I’m in the ulcer victim’s nearest approach to a devil-may-c