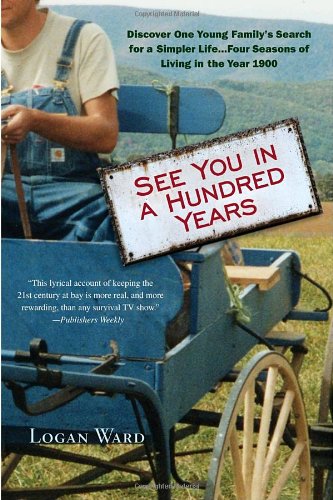

See You in a Hundred Years: Discover One Young Family's Search for a Simpler Life . . . Four Seasons of Living in the Year 1900

$31.89

by Logan Ward

Shop Now

Logan Ward and his wife, Heather, were prototypical New Yorkers circa 2000: their lives steeped in ambition, work, and stress. Feeling their souls grow numb, wanting their toddler son to see the stars at night, the Wards made a plan. They would return to their native South, find a farm, and for one year live exactly as people did in 1900 Virginia: without a car or electricity–and with only the food they could grow themselves. It was a project that would push their relationship to the brink–and illuminate stunning hardships and equally remarkable surprises. From Logan’s emotionally charged battles with Belle, the family workhorse, to Heather’s daily trials with a wood-fired cooking stove and a constant siege of garden pests and cantankerous animals, the Wards were soon overwhelmed by their new life. At the same time as Logan and Heather struggled with their increasingly fragile relationship, as their son relished simple joys, the couple discovered something else: within their self-imposed time warp, they had found a community, a sense of belonging, and an appreciation both for what we’ve lost–and what we’ve gained–across a century of change. "Logan Ward shares his family's brave adventure in this memorable and heartwarming memoir. With fetching candor, he describes his family's escape from the stress of modern living. I found myself completely involved with their experiment. You will find much in this book to think about. It's as valuable as a how-not-to endeavor as it is a how-to inspiration."—Mildred Armstrong Kalish, author of Little Heathens “A meditation on the value of modern living.” –Birmingham News “Ward has crafted a thoughtful, sweet-natured book–one to read s-l-o-w-l-y, by candlelight if possible, with a still mind and a settled heart.” –Hampton Sides, author of Blood and Thunder and Americana “A lively tale, told with admirable honesty.” – Raleigh (NC) News & Observer Logan Ward has written for many magazines, including National Geographic Adventure, Men’s Journal, Popular Mechanics, Southern Accents, and Cottage Living. He lives with his wife, Heather, and their children, Luther and Eliot, in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. Chapter One Goodbye, New York In the City, you don't stargaze. You don't dig through wildflower field guides for the name of that brilliant trumpet burst of blue you saw on your morning walk. You don't hunt for animal tracks in the snow or pause in that same frozen forest, eyes closed, listening for the chirp of a foraging nuthatch. You forget such a creature as a snake even exists. It's as if New York is encased in a big plastic bubble, where humans sit atop the food chain armed with credit cards and Zagat guides. Native wildlife? Cockroaches, pigeons, rats. Disease transmitters. Boat payments for exterminators. Our story begins in the bubble. The year is 2000, the dawn of a new millennium. The Y2K scare is barely behind us. Economic good times lie ahead, with unemployment at an all-time low, the U.S. government boasting record surpluses, and the NASDAQ composite index raising a lusty cheer by topping 5,000. The stock market is making everyone rich—at least on paper. Living in the wealthiest city in the wealthiest nation at the wealthiest moment in history, Heather and I should be happy. We aren't. Which is why I find myself in the back of a cab one day, lurching down Park Avenue, all bottled up with excitement over the news I carry. Out the window I see cows standing amid the tulips on the median strip, with Mies's Seagram Building jutting up behind. They're fiberglass cows. One wears the broad stripes of some third-world flag. Another, the geometric lines of a Mondrian painting. My cabbie tilts his head toward the rearview mirror to catch my eye and says in a clipped Bombayan singsong, "I keep wondering what is the meaning of all these cows." "It's art," I yell through the plastic safety shield. "In my country, cows are for eating," he says, and it dawns on me that since cows are holy in India, he must be Pakistani. Leaning up so I don't have to shout, I say, "Sometimes I wonder if people in this city even know where their hamburgers come from. Last Sunday I was at the Brooklyn Zoo pushing my one-year-old in a stroller, and this girl—she must have been twelve—looks right at a cow in the farm-animal pen and can't say what it is." "A real cow?" "A real cow. It was just a baby, but it was clearly a cow. Anyway, the girl's mother is getting frustrated. She keeps saying, 'Come on, you know what that is.' Meanwhile, my little boy's screaming 'moooo, moooo.' I couldn't believe it." I sink into the seat thinking not my kid, never and feel a rush of joy knowing just how true that is. Then I lean forward again. "I didn't stick around to see if she recognized the goat." "In my country," he says, "goat is a favorite meat." Just then another taxi swerves into our lane. "Hey!" my driver yells, slamming the brakes and banging the horn with the heel of his h