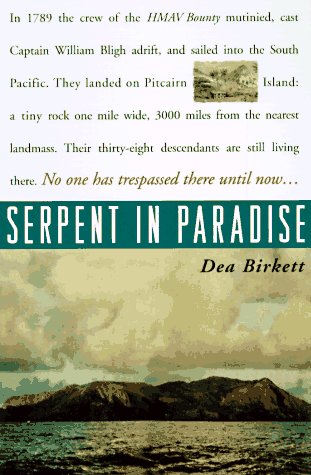

Pitcairn Island, a tiny speck in the South Pacific 3000 miles from the nearest landmass, has had an enduring hold over the imaginations of countless people. The final refuge of the infamous Bounty mutineers, the island holds out the promise of paradise: three square miles of tropical beauty, inhabited by only 37 people. Acclaimed British travel writer and journalist Dea Birkett, obsessed both by the island's enduring image as a secluded Eden, and by the Bounty legend, traveled across the Pacific in a cargo ship and became one of the very few outsiders permitted to land on Pitcairn. Longing to fit in with the islanders, Birkett lived with a Pitcairner family for five months. Initially welcoming, the islanders gradually began to whisper rumors about Birkett, to mount indirect attacks on her character. As she came to realize that being a Pitcairner means more than climbing cliffs and weaving baskets, Birkett saw the darker face of paradise: Pitcairners sacrifice their individuality to the good of the group; with no way to evade their neighbors' watchful eyes, the islanders have no privacy. The island paradise became at last a kind of prison. An engrossing narrative, Serpent in Paradise is an accomplished piece of travel writing about life in one of the world's most unusual places. It is also a deeper examination of the place Pitcairn Island in particular occupies in many imaginations, of the lure of the mythical island paradise, and finally at the dark side of this myth. Most people know the story of the Mutiny on the Bounty , how in 1789 Captain Bligh's crew mutinied then founded their paradise on Pitcairn Island. Two centuries later, the mutineers' descendants still live on Pitcairn with no cars, doctors, crime, or regular contact with the outside world, despite the hordes of paradise-seekers who deluge the island with requests, most of which are refused. After two years' persistence and 4,000 miles aboard a chemical tanker, Dea Birkett finally made her way to Pitcairn, but the island paradise has a dark legacy. Birkett's account is a fascinating look at a tight community with a notorious past and a shady present. Birkett, an English travel author (Spinsters Abroad: Victorian Lady Explorers, Blackwell, 1989) and contributor to numerous magazines, became fascinated with the story of Pitcairn Island after viewing the film The Bounty (1984). Home to the descendants of the legendary mutineers of the HMAV Bounty, Pitcairn is situated 3000 miles from the nearest land in the South Pacific. It took more than two years for Birkett to get permission to visit the island, book passage on a chemical tanker, and arrange to stay with an islander. The 40 inhabitants speak Pitcairnese, a mixture of Polynesian and 18th-century English. Birkett uses Pitcairnese throughout, describing everyday life on the remote island, where everyone drives three-wheel all-terrain vehicles, has electricity only from 6 p.m. to 11 a.m., and uses a "party line" island telephone system. Whenever a ship is sighted, the bell is rung and the entire island population rushes to the jetty to launch long boats so that island produce and souvenirs can be bartered for much-needed supplies. In the end, Birkett fails to "fit" into the tightly knit community she beautifully documents. Over 200 books and five movies have told the tale of the mutiny; this one brings us up-to-date. Recommended for public and academic collections.?John Kenny, San Francisco Copyright 1997 Reed Business Information, Inc. Beguiled by the romance of the South Seas, a young Briton wangles her way to the renowned but seldom visited Pitcairn Island, home to the descendants of Captain Bligh's mutinous crew. Among the most isolated spots on earth, Pitcairn Island lies well away from shipping lanes, but the resourceful Birkett, a freelance writer whose work has appeared in Britain and America, found sponsorship and hitched a ride on a chemical tanker headed for New Zealand that made a brief stopover at the two-and-a-half- square-mile island. In breezily witty fashion, Birkett describes an idiosyncratic collection of 38 islanders whose mixed Polynesian and British ancestry has resulted in rare combinations of physical features and a unique Pitcairnese dialect--something of a cross between archaic English and South Sea languages. With no regular channel to the outside world, the islanders are generally self- sustaining, relying on the occasional ship for precious commodities such as eggs or cooking oil. Birkett proves adept at learning the islanders' crafts (basket weaving and carving), driving their three-wheeled motorcycles, and hiking up and down the steep landscape. To please her adopted family, she regularly attends church (in 1886, the entire population became Seventh Day Adventists), eschews alcohol (until she finds the in-group), and above all else, as the islanders consider themselves misunderstood by the rest of the world, conceals the fact that she is a writer. To her disma