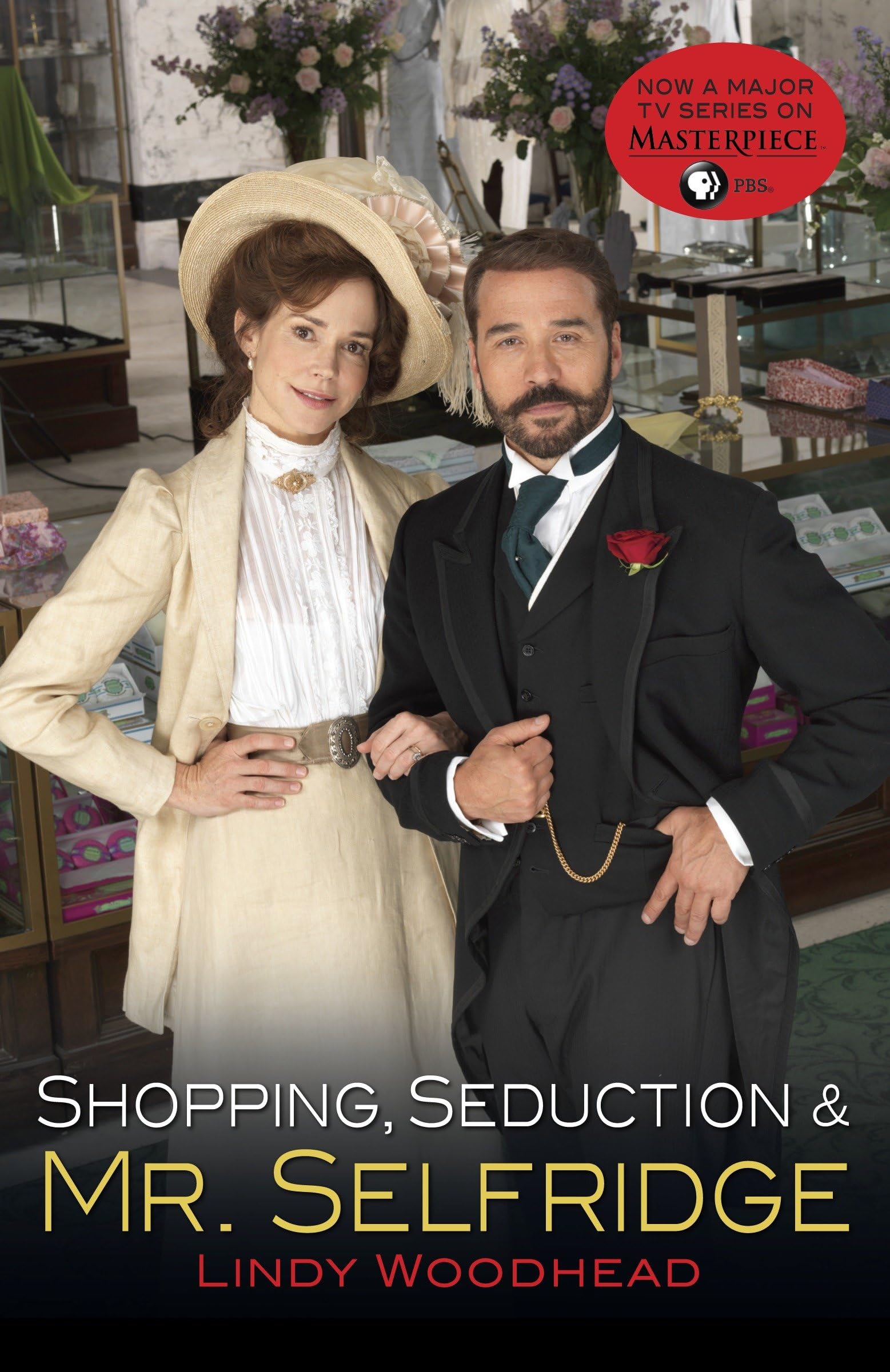

If you lived at Downton Abbey, you shopped at Selfridge’s. Harry Gordon Selfridge was a charismatic American who, in twenty-five years working at Marshall Field’s in Chicago, rose from lowly stockboy to a partner in the business which his visionary skills had helped to create. At the turn of the twentieth century he brought his own American dream to London’s Oxford Street where, in 1909, with a massive burst of publicity, Harry opened Selfridge’s, England’s first truly modern built-for-purpose department store. Designed to promote shopping as a sensual and pleasurable experience, six acres of floor space offered what he called “everything that enters into the affairs of daily life,” as well as thrilling new luxuries—from ice-cream soda to signature perfumes. This magical emporium also featured Otis elevators, a bank, a rooftop garden with an ice-skating rink, and a restaurant complete with orchestra—all catering to customers from Anna Pavlova to Noel Coward. The store was “a theatre, with the curtain going up at nine o’clock.” Yet the real drama happened off the shop floor, where Mr. Selfridge navigated an extravagant world of mistresses, opulent mansions, racehorses, and an insatiable addiction to gambling. While his gloriously iconic store still stands, the man himself would ultimately come crashing down. The true story that inspired the Masterpiece series on PBS • Mr. Selfridge is a co-production of ITV Studios and Masterpiece “Enthralling . . . [an] energetic and wonderfully detailed biography.”— London Evening Standard “Will change your view of shopping forever.”— Vogue (U.K.) “Enthralling . . . [an] energetic and wonderfully detailed biography.”— London Evening Standard “Will change your view of shopping forever.”— Vogue (U.K.) Lindy Woodhead worked in international fashion public relations for more than twenty-five years. During the late 1980s she spent two years as the first woman on the board of directors of Harvey Nichols. Woodhead retired from fashion in 2000 to concentrate on writing. Her first book, War Paint, a biography of Helena Rubinstein and Elizabeth Arden, was published in 2003. She is a regular contributor to The Spectator and The Times Saturday Magazine . A Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, she is married with two sons and lives in southwest London and southwest France. 1. The Fortunes of War “Fashion is the mirror of history. It reflects political,social and economic changes, rather than mere whimsy.” —Louis XIV In 1860, as America braced itself for civil war, business-men began to stockpile goods. No one knew better than the store owners what would happen when fabric became scarce. It wasn’t silks and satins that worried them, it was cotton—and they fretted more about the lack of it than the picking of it. In April 1861, when war was declared and President Lincoln issued his Proclamation of Blockade, speculation in cotton became rife, and panicking Northern mill owners were only too glad to forge associations with men who promised to continue the smooth flow of supplies from South to North. When Union forces captured New Orleans in 1862, trade through the Mississippi Valley became particularly brisk. Cotton was also moved out via Memphis and Vicksburg, all of which kept the mills working—so much so that during the first two years of the war manufacturers still made a healthy profit. By 1863, however, supplies were dwindling and there was a short-age of men to run the machines. American spinning mills went on half-time production. As cotton goods became increasingly scarce, those who had filled a warehouse or two could name their price. In New York, President Lincoln’s friend Alexander Stewart, the acknowledged “merchant prince” of the day, made enormous sums of money, having astutely cornered the market in domestic linen as well as cotton. Given that Mary Lincoln, a woman who clearly sought security through her possessions and for whom shopping was an addiction, spent thousands of dollars at Stewart’s Marble Palace—on one memorable visit she ordered eighty-four pairs of colored kid gloves—it is not surprising that Mr. Stewart was also rewarded with lucrative contracts to supply clothing to the Union army. Indeed, the war seemed to have no effect on the shopping habits of New York’s rich. The media criticized their “hedonistic approach during the daily slaughter wrought by the war,” but the pursuit of fashion carried on regardless. Chicago too enjoyed a profitable war. The small town that had emerged out of the swampy Fort Dearborn just three decades earlier—and where some could still remember Chief Black Hawk and his warriors swooping in to attack—was now the hub of America’s biggest railroad network and the collecting point for food to supply both the East and the army. Awash with opportunity and swimming in cash, sprawling, still muddy, “rough and ready” Chicago became a boomtown. As the farm boys joined the army, production of Cyrus McCormick’s re