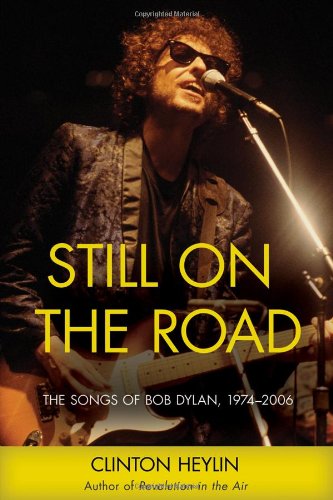

The second of two volumes, this companion to every song that Bob Dylan ever wrote is not just opinionated commentary or literary interpretation: it consists of facts first and foremost. Together these two volumes form the most comprehensive books available on Dylan’s words. Clinton Heylin is the world’s leading Dylan biographer and expert, and he has arranged the songs in a continually surprising chronology of when they were actually written rather than when they appeared on albums. Using newly discovered manuscripts, anecdotal evidence, and a seemingly limitless knowledge of every Bob Dylan live performance, Heylin reveals hundreds of facts about the songs. Here we learn about Dylan’s contributions to the Traveling Wilburys, the women who inspired Blood on the Tracks and Desire , the sources Dylan plagiarized” for Love and Theft and Modern Times , why he left Blind Willie McTell” off of Infidels and Series of Dreams” off of Oh Mercy , what broke the long dry spell he had in the 1990s, and much more. This is an essential purchase for every true Bob Dylan fan. "Clinton Heylin, master explicator of the Dylan canon, has however improbably, sorted it all out for us through the tangled '80's and beyond, completing what he started in Revolution In The Air . The book is essential." Jonathan Lethem "Heylin is at once a researcher, explicator and archivist . . . Taking Dylan's songs in sequential order of composition might seem to be an improbable project, but Heylin documents it with such attention to detail that one marvels at his provable and entirely correct timeline." Shepherd Express Clinton Heylin is the author of Revolution in the Air ; Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades ; Can You Feel the Silence ; From the Velvets to the Voidoids ; Bob Dylan: The Recording Sessions ; Despite the System ; and others. Still on the Road The Songs of Bob Dylan, 1974–2006 By Clinton Heylin Chicago Review Press Incorporated Copyright © 2010 Clinton Heylin All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-55652-844-6 Contents Just Like Another Intro, Some Further Notes on Method, Song Information, 1974, 1975–6, 1977–8, 1979–80, 1980–1, 1982–3, 1984–6, 1987–9, 1990–5, 1996–9, 2000–1, 2002–6, Endnotes, Acknowledgments, A Select Bibliography, Copyright Information, Song Index, General Index, CHAPTER 1 1974 {Blood on the Tracks} On January 3, 1974, Dylan returned to the road (save for 1982–5, for good). On December 30, 1974, having returned "home" to Minnesota for Christmas, he completed the album he had spent most of the year working on, recording, thinking about, and rerecording. Blood on the Tracks was the result of a year of letting his soul bleed into the songs again. And of putting his marriage vows on hold. The process, though, of getting an album out of the fifteen songs he scribbled into his notebook that summer — and two that he didn't — had proven the most tortuous since Blonde on Blonde. Probably because he knew how good they were, he was determined not to let this opportunity go to waste ... {301} LILY, ROSEMARY, AND THE JACK OF HEARTS Published lyric/s: Lyrics 85; Lyrics 04. Known studio recordings: A&R Studios, NYC, September 16, 1974 — 1 take; Sound 80, Minneapolis, MN, December 30, 1974 [BoTT]. First known performance: Salt Lake City, UT, May 25, 1976. The uses of a ballad have changed to such a degree. When they were singing years ago, it would be as entertainment ... A fellow could sit down and sing a song for a half hour, and everybody could listen, and you could form opinions. You'd be waiting to see how it ended, what happened to this person or that person. It would be like going to a movie ... Now we have movies, so why does someone want to sit around for a half hour listening to a ballad? Unless the story was of such a nature that you couldn't find it in a movie. — Dylan, to John Cohen, June 1968 Just six months after John Wesley Harding — "the amnesia" having barely set in — Dylan was trying to figure out how to reconfigure the most ancient form of popular song for an audience brought up on "going to a movie." Six years later, he pulled it off. "Lily, Rosemary, and the Jack of Hearts" sets out to tell, and succeeds in telling, a story "of such a nature that you couldn't find it in a movie" (though Jonathan Taplin at one point thought it could make the transition to celluloid). A ménage à quatre involving the three title characters and Big Jim, the tangled tale ends with only the fair Lily and the Jack of Hearts escaping with their lives. This epic ballad appears to have been wholly inspired by Dylan's experience of making the movie Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid in a genre which suited both ballad and b movies: the Western. "Lily, Rosemary, and the Jack of Hearts" even acts like a shooting script at times. When Big Jim pulls a gun on the Jack of Hearts, only to find that "the cold revolver clicked,"