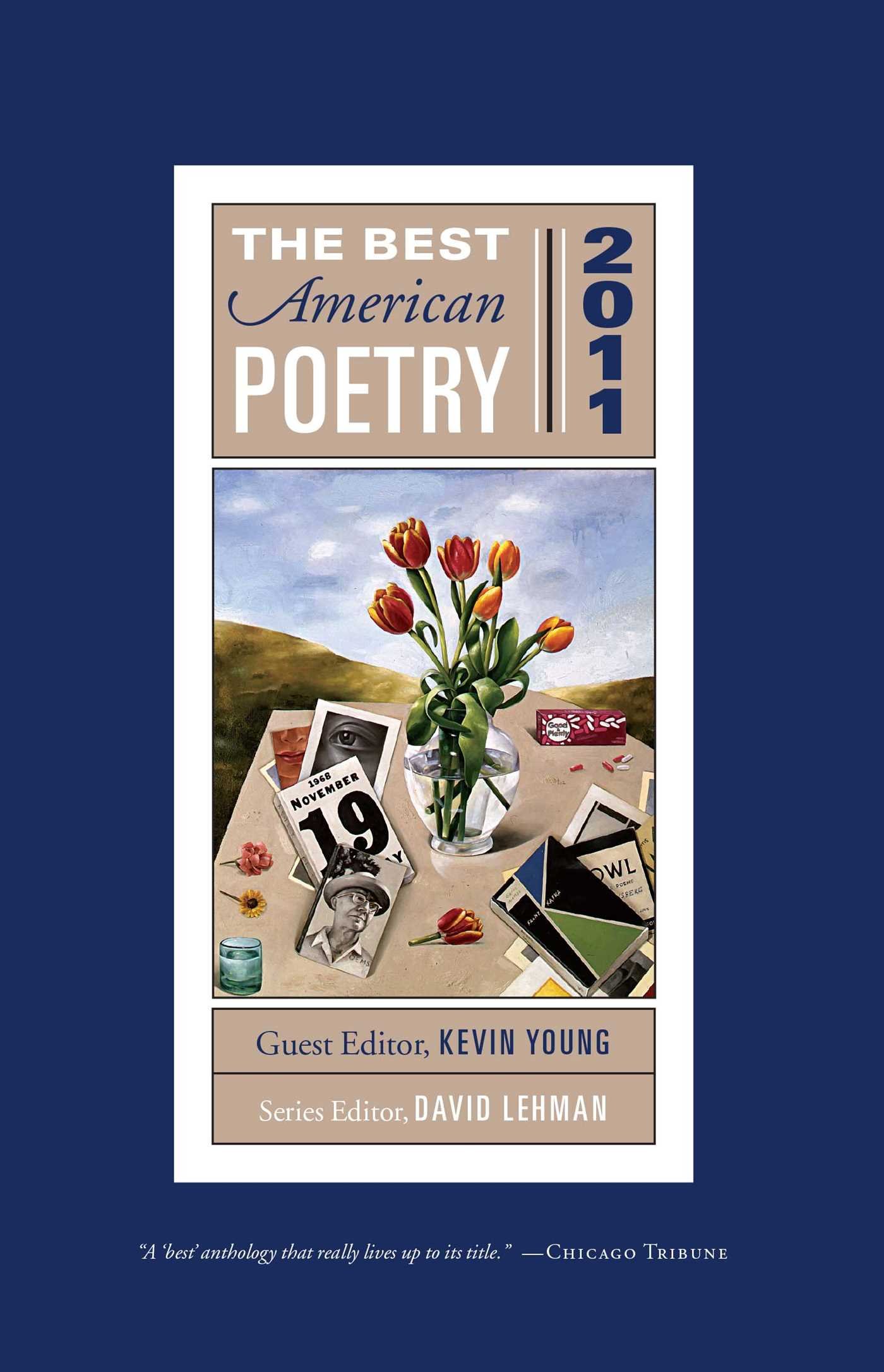

The latest installment of the yearly anthology of contemporary American poetry that has achieved brand-name status in the literary world. David Lehman, the series editor of The Best American Poetry , edited The Oxford Book of American Poetry . His books of poetry include The Morning Line , When a Woman Loves a Man , and The Daily Mirror. He has written such nonfiction books as Signs of the Times: Deconstruction and the Fall of Paul de Man. He lives in New York City and Ithaca, New York. FOREWORD by David Lehman What makes a poem great? What standards do we use for judging poetic excellence? To an extent, these are variants on an even more basic question. What is poetry? Poetry is, after all, not a neutral or merely descriptive term but one that implies value. What qualities in a piece of verse (or prose) raise it to the level of poetry? The questions face the editor of any poetry anthology. But only seldom do we discuss the criteria that we implicitly invoke each time we weigh the comparative merits of two or more pieces of writing. And to no one’s surprise, it turns out to be far easier to recognize the genuine article than to articulate what makes it so, let alone to universalize from a particular instance. Thus, so astute a reader as Randall Jarrell will linger lovingly on the felicities of Robert Frost’s late poem “Directive” only to conclude sheepishly: “The poem is hard to understand, but easy to love.” The standard definitions of poetry spring to mind, each one seeming a near tautology: “the best words in the best order” (Coleridge), “language charged with meaning to the utmost possible degree” (Pound), “memorable speech” (Auden). Other justly celebrated statements may stimulate debate but have a limited practical application. Is poetry the “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” (Wordsworth) or is it precisely “not the expression of personality but an escape from personality” (T. S. Eliot)? The statements contradict each other except in the mind of the reader who enjoys with nearly equal gusto the poetry of the Romantic movement, of Wordsworth and Coleridge, on the one hand, and that of the modernists who reacted so strongly against them (Eliot, Pound) on the other. Poetry is “what gets lost in translation” (Frost); it “strips the veil of familiarity from the world, and lays bare the naked and sleeping beauty” (Shelley); it “is the universal language which the heart holds with nature and itself” (Hazlitt). Although poems do come along that seem to exemplify such statements, the problem remains unsolved except by individual case. Archibald MacLeish’s famous formulation (“a poem should not mean / But be”) is conceptually useful in a class of writers but leaves us exactly where we started. Asking herself “what is poetry and if you know what poetry is what is prose,” Gertrude Stein makes us understand that poetry is a system of grammar and punctuation. “Poetry is doing nothing but using losing refusing and pleasing and betraying and caressing nouns”—a valuable insight, but try applying it to the task of evaluating poems and see if it gets any easier. Wallace Stevens, a master aphorist, has a score of sentences that begin with the words poetry is. Poetry is “a search for the inexplicable,” “a means of redemption,” “a form of melancholia,” “a cure of the mind,” “a health,” “a response to the daily necessity of getting the world right.” It is metaphorically “a pheasant disappearing in the brush” and it is also, in one word, “metaphor” itself. The proliferation of possibilities tells us a great deal about Stevens’s habits of mind. But epigrams will not help the seasoned reader discriminate among the dozens of poems crying for attention from the pages or websites of well-edited literary magazines. The emancipation of verse from the rules of yore complicates matters. It is tough on the scorekeeper if, as Frost said, free verse is like playing tennis without a net. (Some varieties of free verse seem to banish ball as well as net.) But even if we set store by things you can measure—rhyme, meter, coherence, clarity, accuracy of perception, the skillful deployment of imaginative tropes—the search for objective criteria is bound to fail. Reading is a frankly subjective experience, with pleasure the immediate objective, and in the end you read and judge the relative value of a work by instinct. That is, you become aware of the valence of your response, whether it is positive or negative, thumbs-up or -down, before you become aware of why you reacted the way you did. There is in fact no substitute for the experience of poetry, though you can educate your sensibility and become better able to summon up the openness to experience that is the critic’s first obligation—that, and the ability to pay attention to the poem and to the impact it has made on you. Walter Pater asked these questions upon reading a poem or looking at a picture: “What effect does it really produce on me? Does it give m