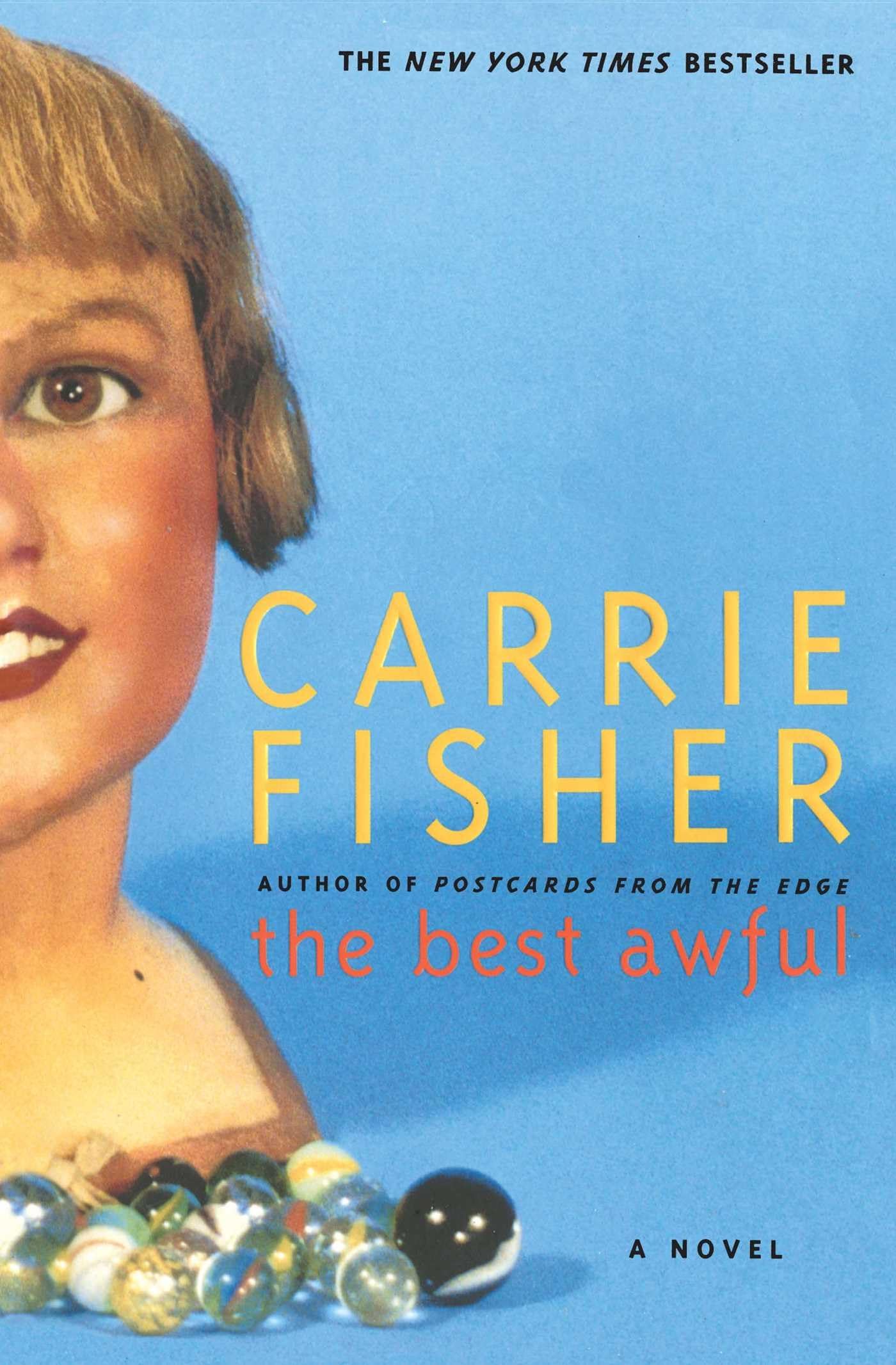

This sequel to the bestselling Postcards from the Edge contains Carrie’s Fisher’s trademark intelligence and wit that brought Postcards to the Hollywood movie screen. When we left Suzanne Vale at the end of Carrie Fisher’s bestselling Postcards from the Edge, she had survived drug abuse, rehab, and Hollywood celebrity. The Best Awful takes Suzanne back to the edge with a new set of troubles—not the least of which is that her studio executive husband turned out to be gay and has left her for a man. Lonely for a man herself, Suzanne decides that her medication is cramping her style, and she goes off her meds—with disastrous results. The “manic” side of the illness convinces her it would be a good idea to get a tattoo, cut off her hair, and head to Mexico with a burly ex-con and a stash of OxyContin. As she wakes up in Tijuana, the “depressive” side kicks in, leading Suzanne through a series of surreal psychotic episodes before landing her in a mental hospital. With the help of her movie star mom, a circle of friends, and even her ex-husband, she begins the long journey back to sanity. The Best Awful is by turns highly comic and darkly tragic, a roller-coaster ride through the dizzying highs and crushing lows of manic depression, delivered with fast and furious wit. People No-holds-barred humor and snappy banter. Vanity Fair Carrie Fisher [is] one of our most painfully hilarious correspondents from the edge of sanity. Carrie Fisher (1956–2016) became a cultural icon as Princess Leia in the first Star Wars trilogy. She starred in countless films, including Shampoo and When Harry Met Sally . She is the author of Shockaholic; Wishful Drinking (which became a hit Broadway production); and four bestselling novels, Surrender the Pink , Delusions of Grandma , The Best Awful, and Postcards from the Edge. Chapter One: The Man That Got the Man That Got Away Suzanne Vale had a problem, and it was the one she least liked thinking about: She'd had a child with someone who forgot to tell her he was gay. He forgot to tell her, and she forgot to notice. He might've forgotten to mention it because he'd hoped she would save him. Making him into a normal "family man" with a wife and a child and a job running a studio. And hadn't she wanted to be saved from certain things also? From life alone? From being childless? From a life that might've looked a little sad from the outside? So, merging their secret hopes for rescue, they'd had a baby with their unwritten pact of androgyny, an androgyny that informed the life they lived out loud. Suzanne had never seen herself as what she called a squeezy tilty girl. She was a breadwinner with a very yang personality. A person who wore a lot of severely tailored little black suits. And Leland Franklin would never be called up for the butch patrol. Not that he was effeminate in any way -- far from it. Suzanne's pregnancy had betrayed their pact, however, transforming her into a girl -- a vulnerable woman even -- leaving Leland to be what he couldn't: a straight and certain man...certain of his sexuality anyway. Looking back, perhaps Suzanne should've guessed based on his affection for Biedermeier furniture or even his fastidiousness with his grooming...she should've known when, toward the end, he'd begun rigorously attending a gym, perfecting a body she knew wasn't being perfected for her. Their alliance had broken under the strain of their attempt at normalcy gone wrong. When their daughter Honey was three, Leland had left her for a man, though initially this was not what he'd said. He'd said he was leaving because Suzanne was crazy. Kept him up all night. Refused to take her bipolar medication, and she would talk talk talk... talk all the time. Maybe she'd talked him out of staying with her. Won the argument for why to leave her without meaning to. After Leland had left -- right after, when feelings were still high, with winds of hurt and blame storming out of her Cape Fear -- he'd mentioned to Suzanne late one evening in a particularly blistering phone call that she might've helped turn him gay, "By taking all that codeine again!" to which Suzanne replied tearfully, "Oh, I'm sorry -- I hadn't read that part of the warning on the label! I thought it said heavy machinery, not homosexuality! Here I could have been driving those big farmyard tractors all along!" and she'd slammed the phone down, red-faced and weeping. After the dust from his departure had settled, she'd found herself with a child, a grudge, and a bright phosphorus gnaw of pain glowing in the hot spot of her chest. It turned out he'd left her with this tender wound of love for him, a warm ache informing her she'd accidently grown to care. He'd outlasted her disinclination to ever love deeply, winning the race to the end of her arm's-length way of figuring everything out until it couldn't hurt her again. Unbeknownst to her, she'd come to look at him with lively eyes tenderized pi