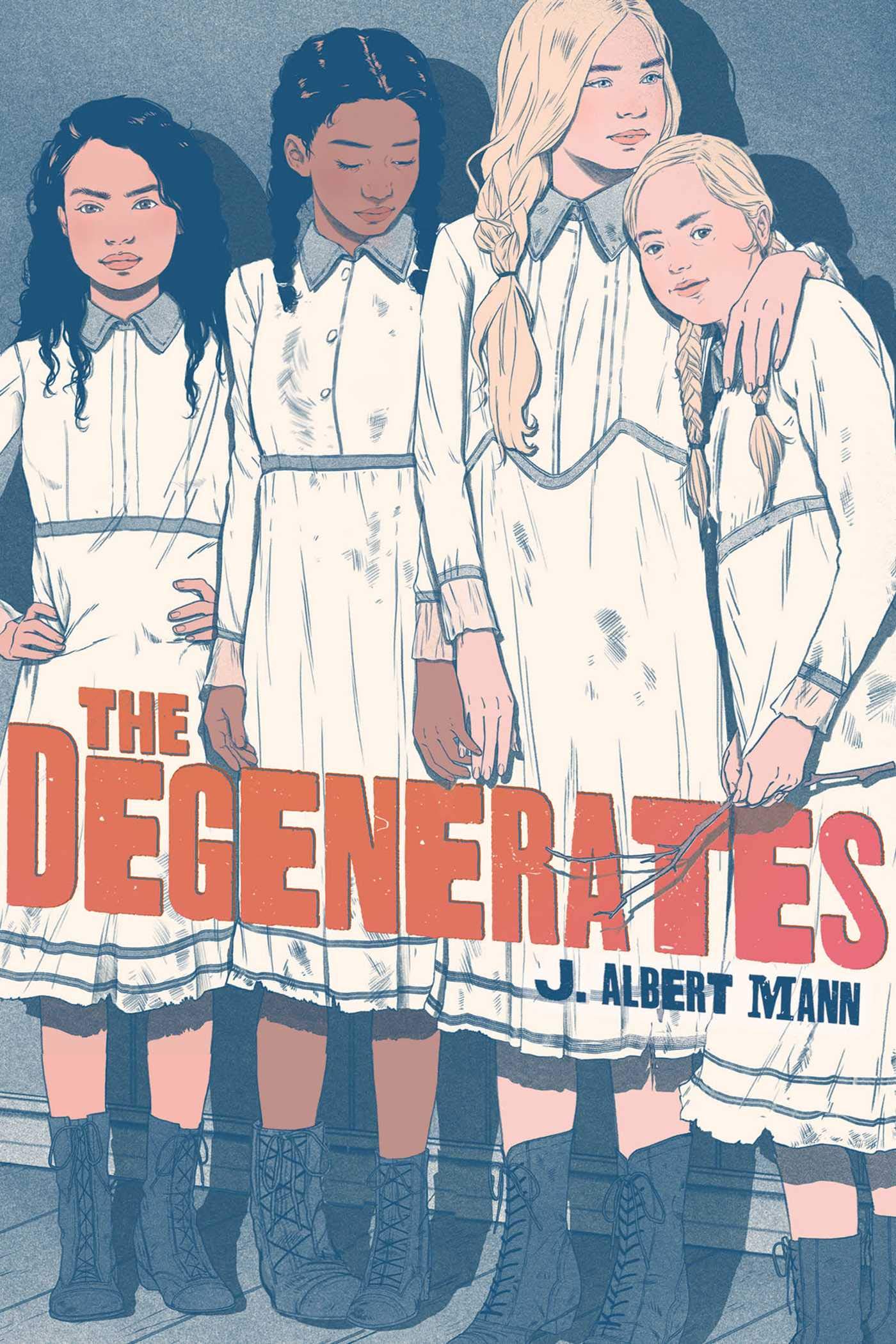

“Respectful, unflinching, and eye-opening.” — Kirkus Reviews “Historical fiction that not only depicts a cruel, horrifying reality but also the strength and courage of the people who had to endure it.” — Booklist In the tradition of Girl, Interrupted , this fiery historical novel follows four young women in the early 20th century whose lives intersect when they are locked up by a world that took the poor, the disabled, the marginalized-and institutionalized them for life. The Massachusetts School for the Feeble-Minded is not a happy place. The young women who are already there certainly don’t think so. Not Maxine, who is doing everything she can to protect her younger sister Rose in an institution where vicious attendants and bullying older girls treat them as the morons, imbeciles, and idiots the doctors have deemed them to be. Not Alice, either, who was left there when her brother couldn’t bring himself to support a sister with a club foot. And not London, who has just been dragged there from the best foster situation she’s ever had, thanks to one unexpected, life-altering moment. Each girl is determined to change her fate, no matter what it takes. “The author portrays the movement's prejudice, racism, and violence with brutal realism; an author's note explains that the doctors' dehumanizing dialogue comes verbatim from real medical notes. Crucially, she reminds readers that such prejudice still exists. . . . Respectful, unflinching, and eye-opening.” -- Kirkus Reviews J. Albert Mann is the author of several middle grade and young adult novels, including The Degenerates and What Every Girl Should Know . She has an MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts in writing for children and young adults. She prefers books with unhappy endings to happy ones. Visit her at JAlbertMann.com. Chapter 1 London couldn’t stop thinking about the girl in the iron lung. The metal barrel had been keeping the girl alive now for two weeks. It was the same amount of time that London realized she had been keeping something alive inside her. One had nothing to do with the other, London knew, but she couldn’t help connecting them. Three miles away a girl was encased in a machine that was pushing air into and pulling air out of her lungs, tethering her to life. Just thinking about it made London suck in a deep breath of chilly October air as she walked down Chelsea, knowing that this air was sinking deep inside her… tethering her to a life, a very small life. Better to think about the machine. She pictured a bellows-like tool shoving air into each of the girl’s lungs, which London imagined looked like the pigs’ bladders hanging out to dry at Flannery’s butcher shop on Decatur. The iron lung fascinated her. Not the polio part. London knew sickness well enough. Sickness had taken both her parents, along with thousands of others, ten years before, when the flu had swept through Boston. The only memory she had of her parents was the morning they’d all docked at the commonwealth pier following the long trip over from Abruzzo. It had been the summer of 1918, and she’d been only four years old, but she remembered her mother’s nervous, excited eyes as the ship pulled alongside the largest building London had ever seen. She remembered her father swinging her onto his shoulders, the smell of his hair, the feel of his smile through the long reach of her arms around his chin. He was dead within a month. Her mother didn’t last much longer. Sickness whisked people away from you in an instant—it was what it was. Girls living day in and day out inside iron machines, that was something else. London felt close to the girl somehow. She herself had spent many nights trapped inside filthy orphanage dormitories or in even filthier foster homes, sleeping in rooms full of people she didn’t know while some sort of bellows-like force kept her alive. Two weeks ago—the day the girl went into the iron lung—London had vomited into the leaf-choked gutter on her way to school. After spitting out as much as possible of the nasty taste of the old lady’s watery oatmeal and wiping the thick spit from her face with the back of her hand, she had turned toward the butcher shop on Decatur Street, and then stood on the sidewalk until Alby came out. It had only taken him a moment to understand. London had always admired this about Alby, how quick-witted he was—his mind whipping colorfully about like the long row of flags lining the front of the Fairmont Copley Plaza on St. James. Her own mind moved more at the speed of the old milk wagons along Meridian. Although the expression on Alby’s face that morning was anything but colorful. Instead it had matched the bleached-out apron he wore, too early in the morning to be splashed with the dark red of blood. When he didn’t move from the shop door, London understood. Alby was done with her. She’d approached him. Controlled. Except for her eyes, which she could feel burning in their sockets. Alby didn’t