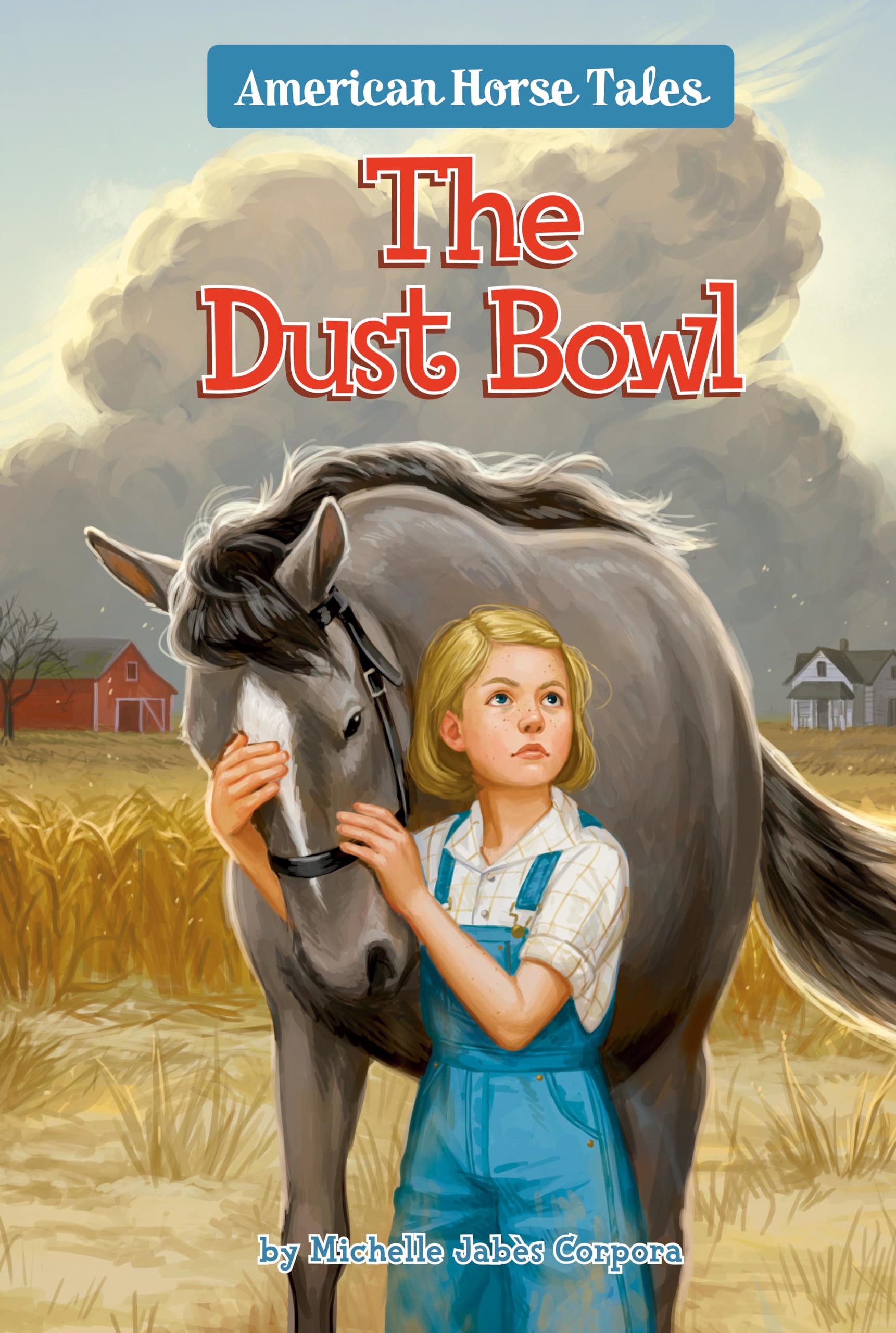

Set in the 1930s Oklahoma, this American Horse Tale is the story of a young girl who makes the difficult decision to leave her family and move to California so she can stay with her horse. A young girl named Ginny and her family are dealing with the hardships of the Great Depression, and in order to survive, her dad decides they must sell their horse, and Ginny's best friend, Thimble. But Ginny will do anything in order to find a way for them to stay together, and chooses to leave her family in Oklahoma and travel west to California. The Dust Bowl is part of a series of books written by several authors highlighting the unique relationships between young girls and their horses. Michelle Jabès Corpora is a writer, editor, community organizer, and martial artist. In addition to working in the publishing industry for more than a dozen years as an editor and concept developer, she has ghostwritten five novels in a long-running middle grade mystery series. American Horse Tales: The Dust Bowl is Michelle's first novel under her own name. Her second novel, The Fog of War: Martha Gellhorn at the D-Day Landings (Pushkin Press), also publishes in 2021. Chapter 1: A Nice Day for a Ride Keyes, Oklahoma July 1936 I stood out by the barn, the paint peeling off it like an old snakeskin. Closing my eyes, I took a deep, deep breath. Most days, the air was chock-full of dust, but that afternoon it was real clear. Full of nothing but sunlight and the smell of Ma’s Ivory Snow laundry soap. I smiled. “Ready, boy?” I asked, a leather lead in my hand. At the other end of the lead, my horse, Thimble, looked over at me. He was light gray with jet black stockings, but since he ain’t hardly ever got a wash, the dust made him look tarnished, like an old spoon. Sometimes I wondered if we all don’t look that color. Once that red dust gets into you, it’s real hard to get out. I’d already checked Thimble’s hooves, eyeballed the tack, and tightened the saddle straps around his belly. He nickered, a soft rumble in his throat. “That’s a silly question, Ginny,” he seemed to be saying. “I’m always ready!” It must have been two weeks since my last ride. Between going to school whenever the weather wasn’t too bad and Ma keeping me busy doing odd jobs around the farm, I barely had time to do more than give Thimble his oats and hay. But not that day. I’d slipped away before Ma could make me do the sweeping like she always did after church on Sundays. As soon as I climbed up onto Thimble’s saddle, all my troubles just melted away. Up there, under the huge, unbroken sky, I finally felt like I was free. Seemed like I wasn’t the only one fixing to run, either. As soon as Thimble reached the open plain outside the farm, he tore into a gallop, kicking up great clouds of dust that hung in the air behind us like a parade of ghosts. The dust was everywhere those days. It crept under the front door, filled up Pa’s work boots, and slipped between our bedsheets at night. Sometimes it even found its way into my breakfast bowl of mush. If I wasn’t so hungry every morning, I’d probably spit it out whenever some of that grit got in. But usually, I just added a little more sugar and tried not to think about it too much. When I was little, there weren’t no dust at all. Back then, Oklahoma was green as green. The corn stood at attention like soldiers in the field, sweet and yellow and as tall as Pa. A cool breeze would blow through the husks when the sun went down, making a sound like shhh, shhh. But when the rain stopped falling, the corn all turned brown—and when the wind turned hot and mean, the corn got too tired to stand up anymore. That’s just how it looked as Thimble and I rode past: laid low on the dusty ground, as quiet and still as a graveyard. It felt like the whole world was holding its breath, and the only sound was Thimble’s hooves thundering across the earth. “Whoa, Thimble,” I said after a few minutes. “Can’t go too far from home now—or we’ll miss supper.” Thimble slowed to a canter and then to an easy jog. “Good boy,” I said, combing my fingers through his mane, which was as thick and black as Pa’s. I’d had Thimble for five years, but it might as well be forever. I still remember Pa telling me that the Atwoods’ old mare, Hannah, had foaled, and that they weren’t sure what to do with the colt because he was so runty. They used their horses to work the fields and didn’t think the wobbly little thing could manage it. I begged Pa to buy him, said I would make sure he came to good use on our farm. Ma said the money would be better spent on fabric to make a dress that wasn’t torn in three places, but I pulled out my prettiest please so Pa couldn’t help but give in. As soon as I laid eyes on him at the Atwoods’ farm, it was love, pure and simple. He ran over to the gate the moment I came up, like he already knew I’d come just for him. But it was what happened on our way back that was really sp