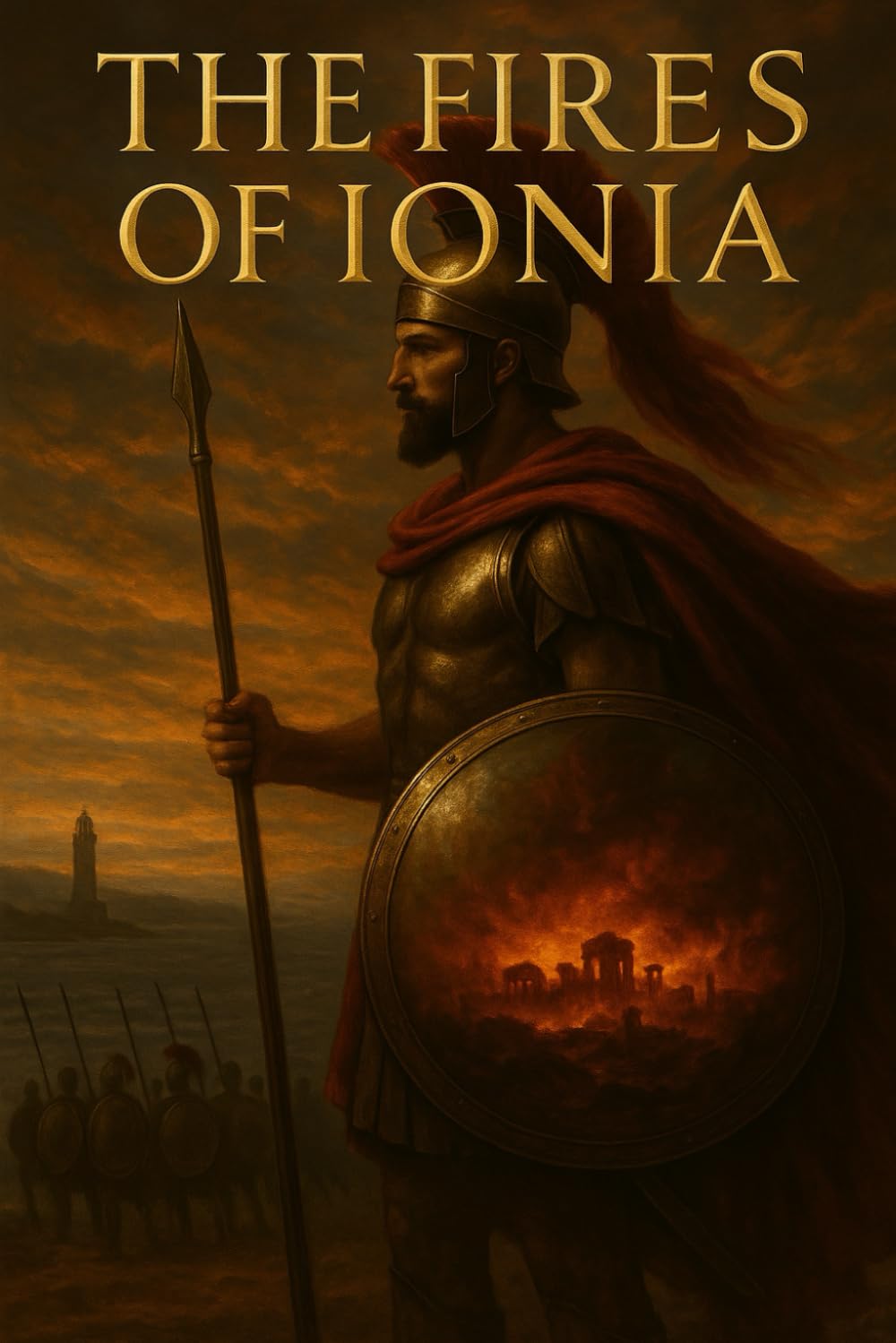

The Fires of Ionia: A tale of rebellion, love, and war at the edge of the ancient Mediterranean—where the road to Marathon and Thermopylae began

$17.99

by Nikandros Thalos

Shop Now

Before the 300 stood at the Hot Gates. Before the Battle of Marathon. There was Miletus — the spark that started it All. Ionia, 499 BC. Aristagoras, the feared tyrant of Miletus, sets out to seize the free Greek island of Naxos, leading the armies of the Persian king Darius and the subjugated cities of Ionia. His uncle Histiæus—scheming from the court of the Great King—has seen to that. Yet what begins as a gesture of obedience soon spirals into reckoning. Alliances fracture. Shadows lengthen. And by crossing the sea, Aristagoras begins to confront the man he must become. Flanked by the companions he trusts—Elenos the giant, Scylas the sea-born, and Proserpine, the mysterious Scythian—he walks a path that may ignite all of Ionia… and lead him against the millions of the Great King’s armies. For Obedience was only the beginning. And Freedom is always paid in blood. Based on the accounts of Herodotus, this epic novel takes us to the first spark that ignited the Persian–Greek wars—the uprising for freedom that enraged King Darius and set in motion his punitive campaign against Athens, paving the way for the later full-scale invasion of Greece by his son, Xerxes. Excerpt: The Persian infantry continued to slam against them. Aristagoras felt his arm jolt—that instant of resistance, that sudden tightening of muscle when the blade has struck home, when the weapon no longer moves because the body before it has given way. The iron tip of his lance had punched through wicker, into flesh, into something solid. He tried to wrench it free. Too late. It caught. And then he felt it—a hand. Someone had seized the shaft, pulling at it, dragging it toward them, preparing to strike in return. Aristagoras was faster and let the lance go. And now—there was no space left. He felt it—the edge of complete will and physical failure, pressing close. His own limbs were giving out. Every muscle in his body was locked in strain. He pushed, but there was nowhere to push, no forward momentum, only a desperate resistance against a force greater than any man alone could hold. He could not move. He could barely breathe. The curve of his shield was the only thing keeping his chest from being crushed outright, from having his ribs caved in by the sheer weight of men. He could see the Persians opposite him, faces pale, eyes wild, mouths gasping like fish dragged from the sea. Persian shields were not curved – they could not breathe at all. His legs threatened to seize, his stomach clenched in a vice of burning cramps, his arms were beyond pain, beyond exhaustion. His body screamed. And then—silence. No cries of war. No clamor of weapons. Only this. This awful, grueling test of endurance. The othismos —the final, grinding pressure of two locked armies, neither yielding, neither winning, an endless tide of force met with equal resistance. All strength was now spent in this one moment, this battle of attrition, this nameless, breathless crush of bodies where neither side could move, where death came not by the sword but by suffocation. And yet—the Greeks had held. Somewhere, in the chaos, he felt it. The enemy behind the row of suffocated Persians of the first lines pushed harder, but it was the push of desperation. Short, sharp thrusts, erratic and panicked, seeking any opening, any weakness, not with confidence but with fear—a drowning man thrashing for air. The pressure did not cease. Aristagoras, trapped in the front line, felt the bodies of his own men pressing against his back, holding him forward with all their might, preventing him from yielding an inch beneath the enemy’s push. Before him, the Persians continued to pile forward, forcing the ranks of their dead against him, pressing ever harder.