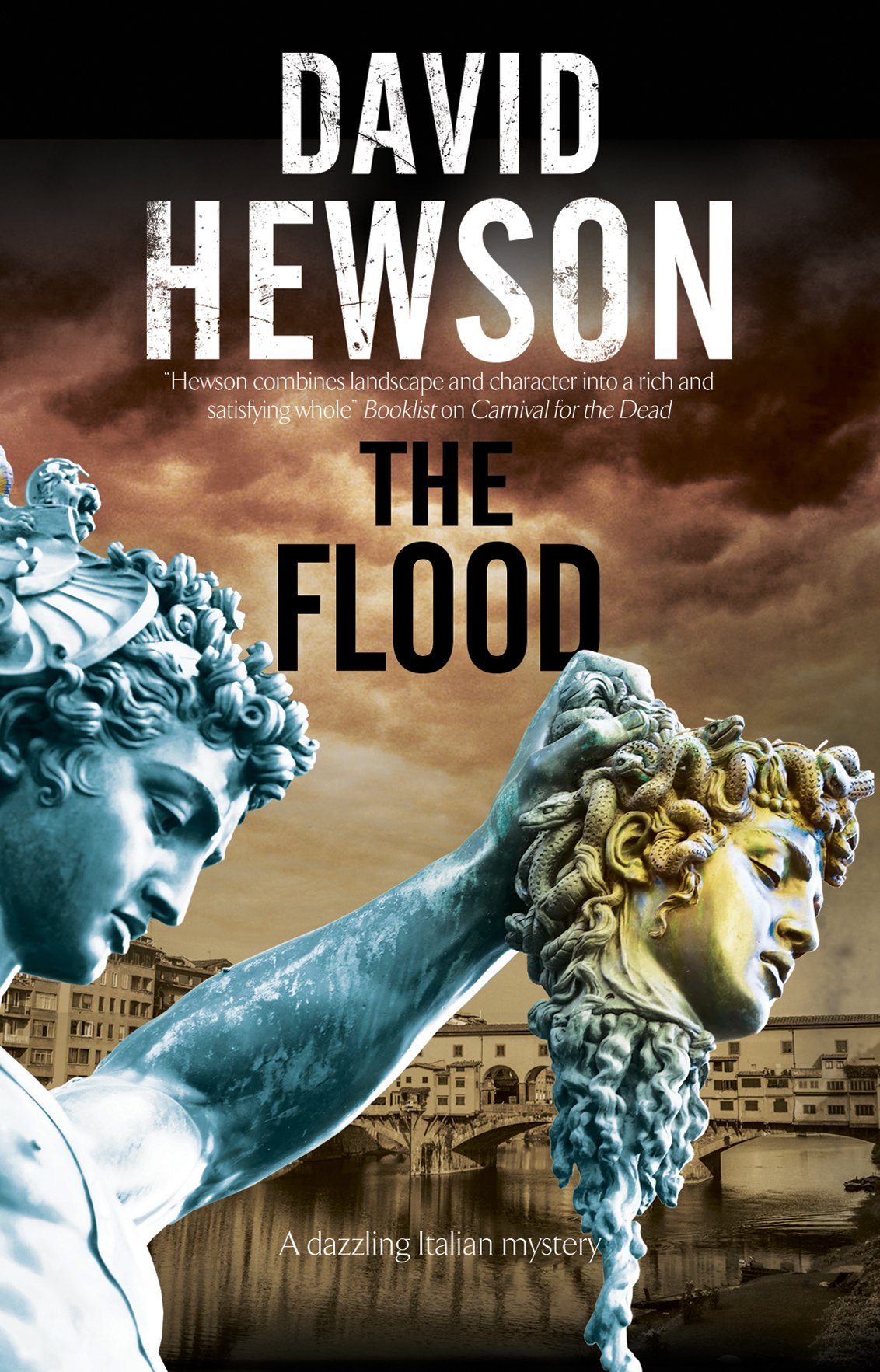

A dazzling Italian mystery, rich in intrigue and dark secrets, from an internationally bestselling crime writer at the height of his powers. Florence, 1986. A seemingly inexplicable attack on a church fresco of Adam and Eve brings together an unlikely couple: Julia Wellbeloved, an English art student, and Pino Fratelli, a semi-retired detective who longs to be back in the field. Their investigation leads them to the secret society that underpins the city: an elite underworld of excess, violence and desire. Seeped in the culture of Tuscany’s most mysterious city, The Flood takes the reader on a dazzling journey into the darkness in Florence’s past: the night of the great flood in 1966 … Readers of Donna Leon and Michael Dibdin or Italian authors Andrea Camilleri and Carlo Lucarelli will find this gripping" Library Journal "Hewson excellently integrates episodes from Florentine history into the lives of his intriguing heroes. . . Readers of Donna Leon and Michael Dibdin or Italian authors Andrea Camilleri and Carlo Lucarelli will find this gripping" ― Library Journal “Hewson spins an engrossing tale of art and murder" ― Booklist David Hewson is a former journalist with The Times, The Sunday Times and the Independent. He is the author of more than twenty-five novels including his Rome-based Nic Costa series which has been published in fifteen languages. He has also written three acclaimed adaptations of the Danish TV series, The Killing. He lives near Canterbury in Kent The Flood By David Hewson Severn House Publishers Limited Copyright © 2015 David Hewson All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-84751-625-1 Contents Cover, A Selection of Titles by David Hewson, Title Page, Copyright, Epigraph, Friday, 30 October 1942, Friday, 4 November 1966, Monday, 3 November 1986, Tuesday, 4 November 1986, Friday, 4 November 1966, Wednesday, 5 November 1986, Thursday, 6 November 1986, December 1986, CHAPTER 1 Friday, 30 October 1942 Rome The boy was four, a pretty child, slim, dark-haired with bright and thoughtful eyes. On this cold, wet day he stood by the bridge to the Castel Sant'Angelo, the city side, not far from home, staring at the stone angels and the vast brown shape across the river. They said it was once the tomb of an emperor, one of the greatest Rome had ever known. But he was a child, so it reminded him of nothing more than the little drum he had in their cramped one-room apartment in the ghetto, the only toy he owned. Down the Lungotevere soldiers marched in dark uniforms, rifles to their shoulders, gleaming bayonets pointing at a sky so flat and lacking in colour he might have drawn it with a soft pencil and a sheet of paper. He wondered if these serious, frightening men thought their blades could pierce the clouds themselves, slashing their leaden bellies, bringing the heavens down to earth. His father said the soldiers could do anything they wanted now. The boy didn't understand what that meant. But in the morning warplanes had flown over the city, their low and threatening engines bellowing like the voice of a great mechanical storm. From the windows of the great palace in the Piazza Venezia the man they called 'Il Duce' had spoken to a vast, adoring crowd. Best not go, his mother told him. We're not welcome there. And all the time it rained. He stared at the river, swollen to a torrent, muddy brown, with branches and debris floating on the surface as it raced through Rome. He'd heard there'd been floods before, times when the Tiber burst its banks and brought its freezing, dank presence into the crowded city itself. An inquisitive, curious child, he wondered what a flood might be like. Did people take to boats? Was there a new danger brought into a world that already seemed fragile and perilous? He couldn't swim, had never learned. It wasn't a good idea to go to the baths, they said. Best to stay home, in the ghetto, safe among those who were like you. Which meant ... he wasn't sure. The other families had habits, rituals, a certain style of dress. On the day called Sabbath they turned more stony-faced than usual and went to the synagogue. But not so much of late, and never in his case. The three of them – father, mother, son – were 'secular', whatever that meant. One day he'd ask. Not now. Across the bridge, life was different. Bigger, brighter, bolder, more colourful. Safer too. The Vatican was there, another country, one ruled by the Pope, a man from a different religion, another life. That place was set apart from his world in a way the boy couldn't begin to comprehend. St Peter's, the Pope's beautiful basilica, with its vast, bright dome, stood on a hill, apart from ordinary Romans. The flood, if it came, would never reach there. Those severe men in their bright robes, cardinals and bishops, the ones he'd seen from time to time scuttling about Rome looking miserable and worried, would hide behind their pale brick walls and let the world outside go an