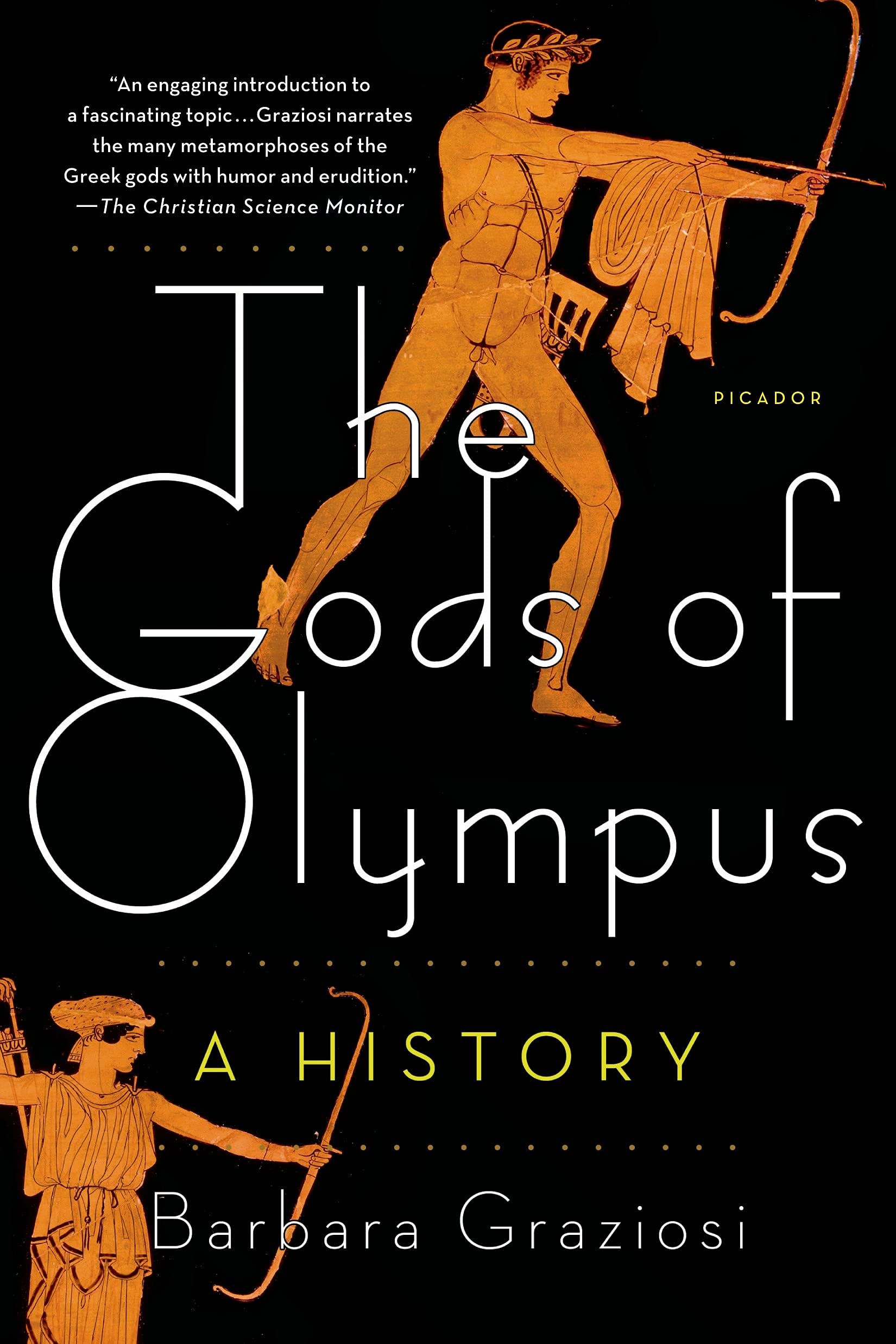

The gods of Olympus are the most colorful characters of Greek civilization: even in antiquity, they were said to be cruel, oversexed, mad, or just plain silly. Yet for all their foibles and flaws, they proved to be tough survivors, far outlasting their original worshippers. In Egypt, the Olympian gods claimed to have given birth to pharaohs; in Rome, they led respectable citizens into orgiastic rituals of drink and sex. Under Christianity and Islam they survived as demons, allegories, and planets. And in the Renaissance, they triumphantly emerged as ambassadors of a new, secular belief in humanity. In a lively, original history of mythology, Barbara Graziosi offers the first account to trace the wanderings of these inventive deities through the millennia. Drawing on a wide range of literary and archaeological sources, The Gods of Olympus opens a new window on the ancient world and its lasting influence. “Informed by considerable expertise, yet wears its learning lightly . . . A rich and stimulating introduction to the ancient Greek and Roman worlds.” ― Times Literary Supplement (London) “An engaging introduction to a fascinating topic . . . Graziosi narrates the many metamorphoses of the Greek gods with humor and erudition.” ― The Christian Science Monitor “Cutting-edge history . . . Deploying an intriguing combination of old-fashioned and inventive approaches to the classical world and its reception, Barbara Graziosi here breaks new ground in the interpretation of the major Greek gods.” ― Times Higher Education (London) “There is still life in the Olympians . . . An erudite and engaging account of their history and remarkable survival.” ― The Literary Review (London) “Graziosi's writing is accessible and entertaining, her passion for her subject obvious . . . A comprehensive and absorbing study.” ― Shelf Awareness Barbara Graziosi is the author of Inventing Homer and Homer in the Twentieth Century , among other works. In 2011, she provided the introduction and notes for a new translation of the Iliad for Oxford World’s Classics. A professor of classics at Durham University, Graziosi is also a contributor to The Times Higher Education Supplement , the London Review of Books , and BBC radio programs on the arts. The Gods of Olympus is her first trade book. She lives in the U.K. 1 At Home in Greece Tall, broad, and covered in snow for much of the year, Mount Olympus stands alone, fully visible from every side. It dominates the landscape for miles; its dazzling peaks seem particularly incongruous when viewed from the hot, low plains around. From the sea, the mountain sometimes looks like a cloud. In antiquity, Mount Olympus lay very much off the beaten track. People had little reason to go near it, and no incentive at all to climb it, but they could see it—and in turn they felt observed. The Greeks thought that the gods lived among the mountain’s peaks and watched what happened down below. Poets elaborated on this notion. Homer described Mount Olympus precisely, mentioning its “many summits,” “abundant snow,” and “steepness” and giving an indication of just where it was. At the same time, he suggested that this mythical residence of the gods was not quite what it seemed: “Olympus is never shaken by winds, hit by rain, or covered in snow; cloudless ether spreads around it, and a bright aura encircles it.”1 So Olympus was both a particular landmark and a place of the mind. Greek communities could see the mountain, agree about its sacredness, and feel united by a shared sense of landscape; but they were also reminded that the gods did not live in our world and were never subjected to the indignities of bad weather. It is unclear when the mountain first became associated with the gods. In the poems of Homer, the most important deities are explicitly called “the Olympians,” but he was not necessarily the first to place them on the sacred mountain. The Iliad and the Odyssey, in the form in which we have them, date to the archaic period (roughly the eighth to the sixth century BC), and the Greek peninsula was settled long before that time. We can reconstruct, on linguistic grounds, that the Greeks were descended from speakers of a language also related to Sanskrit and Latin as well as to Germanic, Slavic, and other linguistic groups, and which is conventionally called “Indo-European.” Migrating from central Asia, Indo-European speakers gradually settled in Europe and introduced broadly shared notions of the gods. So, for example, the Greek Zeus is related to the Sanskrit Dyáus Pitar: they are both versions of the same supreme god, ruler of the sky. It is unsurprising that in Greece, this Indo-European god settled on Mount Olympus, the tallest landmark in the area. It is more difficult to establish just when this happened. Answering that question requires dating the Indo-European migrations and investigating the roots of Homeric epic—both of which are controversial subjects. Impressive civil