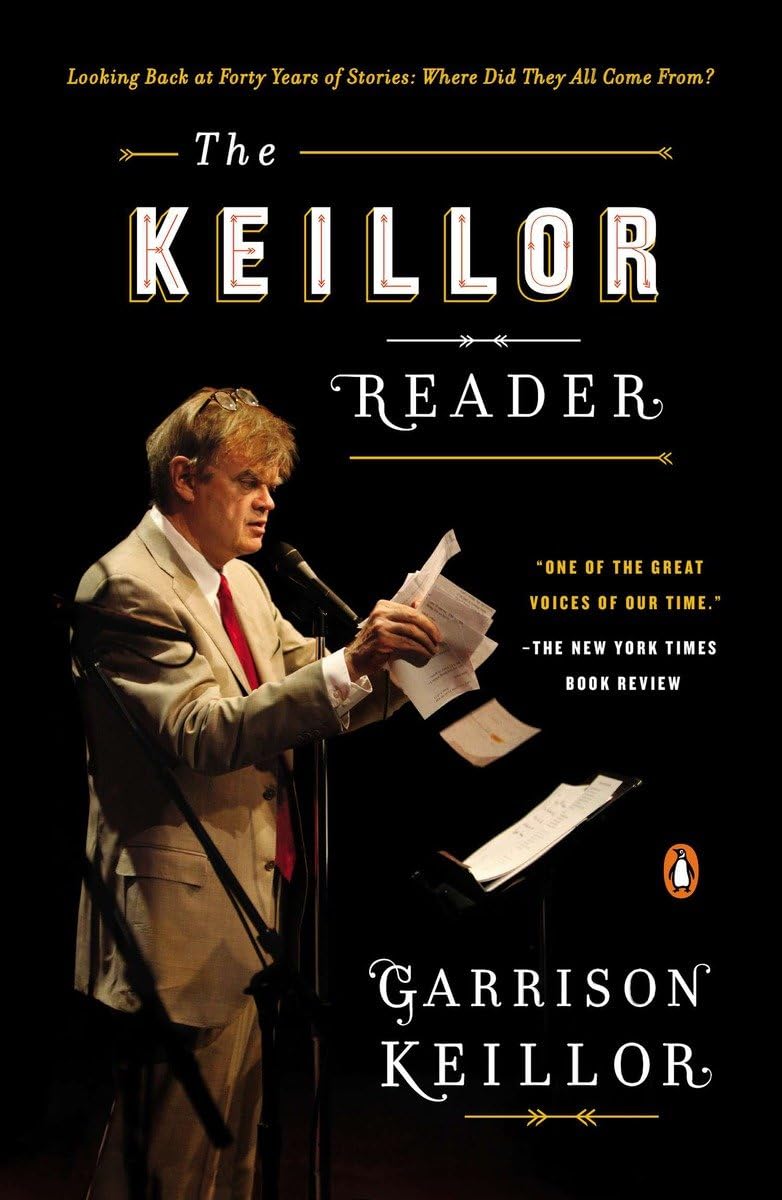

The Keillor Reader: Looking Back at Forty Years of Stories: Where Did They All Come From?

$11.35

by Garrison Keillor

Shop Now

Stories, monologues, and essays by Garrison Keillor, founder and host of A Prairie Home Companion The first retrospective from New York Times bestselling author Garrison Keillor celebrates the humor and wisdom of this master storyteller. With an introduction and headnotes by the author, along with accompanying photographs and memorabilia, The Keillor Reader brings together a full range of Keillor’s work. Included are the “Pontoon” monologue, in which twenty-four Lutheran pastors capsize a boat as a parasail and hot-air balloon maneuver above; the Alaska adventures of professional wrestler Jimmy “Big Boy” Valenti; a new version of “Casey at the Bat”; an imaginative memoir of life at the New Yorker ; and a set of precepts for life, “What Have We Learned So Far?” Praise for The Keillor Reader : “Our bard of small-town melancholy and nostalgia . . . Keillor is terrific, as always, at describing man’s ability to wince in the face of hardship or boredom. Also winning in this book are the behind-the-scenes glimpses that Keillor gives us of ‘A Prairie Home Companion’ . . . one is moved to beam back at Keillor the amount of charity he has beamed at all his characters.” —The New York Times “Wry, wistful, nostalgic . . . by turns cheerful and fatalistic, homespun and outrageous.” —Chicago Tribune “Keillor spin[s] his entire life experience into tales that may be fantastical but are always . . . true to life . . . honoring it, in all its wild permutations and possibilities. . . . This gem of a book will resuscitate you.” —Minneapolis StarTribune “What really appeal[s] about Garrison's work[s] . . . is that they're so human . . . so wonderfully specific and funny that they become universal, and manage to move across generations.” — MinnPost “Heir to Mark Twain, James Thurber and E. B. White, Keillor offers more than laconic, sometimes-rueful, reports from the fictional Midwestern town of Lake Wobegon. Besides selected Prairie Home Companion monologues—written in an adrenaline rush on the morning of each show—this collection contains poetry, fiction and assorted essays, each introduced by autobiographical musings. . . . Lovely.” — Kirkus Reviews Praise for Garrison Keillor : “Keillor is very clearly a genius. His range and stamina alone are incredible—after 30 years, he rarely repeats himself—and he has the genuine wisdom of a Cosby or Mark Twain. He's consistently funny about Midwestern fatalism . . . and he's a masterful storyteller.” — Sam Anderson, Slate "Keillor has always been a great cataloger, equal parts Homer and Montgomery Ward, . . . as aware of life's betrayals and griefs as [he] is of the grace notes and buffooneries that leaven everyday existence. Keillor's Lake Wobegon books have become a set of synoptic gospels, full of wistfulness and futility yet somehow spangled with hope." — Thomas Mallon, New York Times Book Review "A literary cartographer would find it necessary to trace, in forceful blue lines, tributary streams running from Mark Twain and Sherwood Anderson to the Wobegonian river of stories and novels that has issued from Garrison Keillor for more than 20 years." — Chicago Tribune Garrison Keillor is the founder and host of A Prairie Home Companion , author of nineteen books of fiction and humor, and editor of the Good Poems collections. A Minnesota native, he lives in St. Paul and New York City. ***This excerpt is from an advance uncorrected proof.*** Copyright © 2014 by Garrison Keillor Introduction When I was twenty and something of a romantic, I considered dying young and becoming immortal like Buddy Holly (twenty-two), James Dean (twenty-four), and Janis Joplin (twenty-seven) so that people could place bouquets on my grave and think what a shame it was that I never fully realized my enormous talent. But I didn’t have enormous talent. Some people believed I did because I wrote poems and was shy, didn’t make eye contact, kept to myself. (Nowadays you’d say “high-functioning end of the autism spectrum,” but back in the day oddity was interpreted differently.). Anyway, death didn’t occur. I never needed to charter a plane in a snowstorm as Buddy did, and a car like James Dean’s Porsche 550 Spyder was way beyond my means, and heroin was not readily available in Anoka, Minnesota, so onward I went. I had a lot to think about other than immortality—sex, of course, and how to avoid going to Vietnam and dying young in a stupid war, and then I started a radio show called A Prairie Home Companion, which ate up all my time—a man has to work awfully hard to make up for lack of talent—and suddenly I was forty, which is too old to die young, so I forgot about it and headed down the long dirt road of longevity, and thus arrived at seventy, when I took time to sit down and read my own work and see what is what. I started out with No. 2 pencil and pads of paper, then acquired an Underwood manual typewriter with a faint f and a misshapen O. You had to poke the