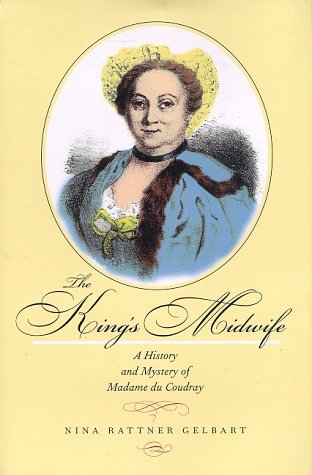

The King's Midwife: A History and Mystery of Madame du Coudray

$61.11

by Nina Rattner Gelbart

Shop Now

This unorthodox biography explores the life of an extraordinary Enlightenment woman who, by sheer force of character, parlayed a skill in midwifery into a national institution. In 1759, in an effort to end infant mortality, Louis XV commissioned Madame Angélique Marguerite Le Boursier du Coudray to travel throughout France teaching the art of childbirth to illiterate peasant women. For the next thirty years, this royal emissary taught in nearly forty cities and reached an estimated ten thousand students. She wrote a textbook and invented a life-sized obstetrical mannequin for her demonstrations. She contributed significantly to France's demographic upswing after 1760. Who was the woman, both the private self and the pseudonymous public celebrity? Nina Rattner Gelbart reconstructs Madame du Coudray's astonishing mission through extensive research in the hundreds of letters by, to, and about her in provincial archives throughout France. Tracing her subject's footsteps around the country, Gelbart chronicles du Coudray's battles with finance ministers, village matrons, local administrators, and recalcitrant physicians, her rises in power and falls from grace, and her death at the height of the Reign of Terror. At a deeper level, Gelbart recaptures du Coudray's interior journey as well, by questioning and dismantling the neat paper trail that the great midwife so carefully left behind. Delightfully written, this tale of a fascinating life at the end of the French Old Regime sheds new light on the histories of medicine, gender, society, politics, and culture. In The King's Midwife , scholar Nina Rattner Gelbart takes on a daunting task: the biography of a woman so fiercely private (or should that be public?) that she left no record at all of her personal life. "In her hundreds of letters there is never a single mention of her origins, parents, childhood, siblings, education, young adulthood, training, marriage if there was one, children if she had any, friends outside of her work," Gelbart writes, with more than a touch of frustration. What we do know about Madame du Coudray is this: in 1750, spooked by reports that the French population was in decline, King Louis XV appointed her to travel throughout the country, training young peasant women to assist at live births. For 30 years, du Coudray crisscrossed the provinces in pursuit of this goal, using a life-size obstetrical mannequin that she'd invented as a teaching aid. Gelbart relies on du Coudray's voluminous correspondence with regional authorities to construct her portrait of a driven, proud, politically savvy, and fiercely ambitious woman. To make her way as an 18th-century woman in the world of the male medical establishment--not to mention the royal court, and later, postrevolutionary France--du Coudray seems to have downplayed her interior life as much as possible. Yet Gelbart makes "a virtue of necessity" by using the very incompleteness of du Coudray's story to illuminate the larger issues at stake--the "history and mystery" encountered when writing any biography: "Historians always have to work with fragments and lacunae, with revelations and secrets. We may crave coherence and synthesis, but because much remains indecipherable we do not get it." Despite the ultimate "unknowability" of du Coudray and her motives, Gelbart does an admirable job in bringing her to life through her public works. The King's Midwife is a "scholarly" biography--a statement that might justifiably strike fear in the heart of the stoutest reader--but Gelbart keeps the academese to blessed minimum. For the most part, this is a lively and well-written account of an exceptional life. This is a fascinating book by a prize-winning historian (Feminine and Opposition Journalism in Old Regime France, 1987). Beautifully written and rooted in extensive archival research, it recounts the life and work of a Parisian midwife who in 1759 was commissioned by Louis XV to launch a nationwide crusade to professionalize midwifery. Worried about depopulation and informed by the spirit of the Enlightenment, the king named Madame du Coudray as royal emissary charged with traveling throughout France to teach the art of childbirth. Aided by a textbook on obstetrics that she herself had authored and a life-sized obstetrical mannequin also of her own invention, du Coudray taught in nearly 40 cities and reached approximately 10,000 students. This work vividly describes the details and difficulties of early modern childbirth as well as skillfully analyzing the meaning of du Coudray's politics and feminism. Facing political obstacles from hostile doctors, other midwives, and local religious authorities, du Coudray worked within the system to create a reputation and role for herself and the niece who would be her successor. Highly recommended for specialists in women's history, French history, and the history of medicine.?Marie Marmo Mullaney, Caldwell Coll., NJ Copyright 1998 Reed Business Informatio