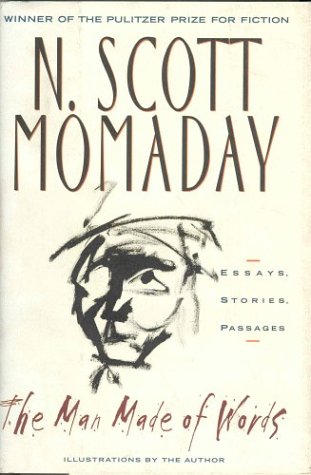

Collects the author's writings on sacred geography, Billy the Kid, actor Jay Silverheels, ecological ethics, Navajo place names, and old ways of knowing The winner of the 1969 Pulitzer Prize for fiction for his novel, House Made of Dawn , N. Scott Momaday is renowned as an influential Native American writer. In this collection of essays he turns his attention to the differences between oral and written cultures; to places he has visited and lived; and to the weighty issues of government Indian policies and the enduring damage they continue to inflict. He writes movingly of his Kiowa forebears, and he teaches us great lessons about mankind and its relationship to nature. Momaday is a deeply thoughtful observer and a graceful writer, and the essays in The Man Made of Words are both provocative and elegant. The son of a Kiowa father and a mother who knew only English, Momaday, winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1968 for his novel House Made of Dawn, was surrounded by the sounds of two languages. In this volume, Momaday collects stories and essays written over the past 30 years that focus on language, the land, and the relationship between Native Americans and whites. In stories about his travels, Momaday describes some of the places he has visited?Russia, Bavaria, Granada?with great beauty. In the stories about people and animals, his subjects come alive on the page. Memorable portraits include one of Jay Silverheels (Tonto in the Lone Ranger television series) and an endearing dog, Cacique del Monte Chamiza (the author's black Labrador retriever). This volume is a good addition to, but not a substitute for, the author's poetry and fiction. Highly recommended for public and academic libraries.?Caroline A. Mitchell, Washington, D.C. Copyright 1997 Reed Business Information, Inc. Early as well as recent work appears in this collection of essays by the eminent Native American writer. Together they reveal how consistent Momaday's stately, oratorical voice has been during his 30-year career. Consistent, too, has been his concern for humanity's place in the natural world and for the spiritual messages Native American traditions offer an alienated society. Momaday's reminiscences of tribal elders, his lively way with a traditional story, his wonder at natural beauty--these are not mere embellishments on the political analysis that he weaves into the essays; rather, they are vital components of Momaday's complex way with words. The reasons for that complexity are suggested by the Kiowa story referred to by the book's title. It is about an arrow maker who, aware of a prowler outside his home, uses words to engage as well as distract the intruder, for possibly the presumed enemy is really a lost friend. Momaday clearly identifies with that legendary hero, and he points his words toward our fully understanding hearts. Patricia Monaghan A noteworthy collection of essays and occasional prose pieces by the doyen of Native American letters. Momaday (The Ancient Child, 1989, etc.) here gathers some 30 pieces, ranging from a memoir of a stroll on a Greenland beach to a eulogy for the Mohawk actor known as Jay Silverheels. Most of these pieces are very short, a few only a page or two in length. As a result, some are only glancing, never quite getting into their subjects; this is especially evident in Momaday's essays on his travels to Germany and Russia, pieces that barely transcend the run of dentist's-office magazine fluff. Such lapses are few, though, and he is much better when he writes more at length on places of which he has a deep knowledge, especially the sacred geography of his native Kiowa landscape and the dry parts of New Mexico, where Billy the Kid once rode. Momaday has been nursing an interest in the Kid for years now, and several of these pieces turn to considering the unfortunate outlaw, a young man of mythicized history who is, Momaday concludes, ``finally unknowable.'' Momaday is no tree-hugger, but he presses the case for a mature ecological ethic that ``brings into account not only man's instinctive reaction to his environment but the full realization of his humanity as well.'' The best pieces in the book, such as a wonderful essay on Navajo place names, combine this ethic with a profound attention to local knowledge and old ways of knowing; echoing Borges, Momaday proclaims that for him paradise is a library, but also ``a prairie and a plain . . . [and] the place of words in a state of grace.'' No matter how incompletely developed, these anecdote-driven pieces are marked by Momaday's nearly religious attention to language and ``the music of memory.'' To read him is to be in the company of a master wordsmith. -- Copyright ©1997, Kirkus Associates, LP. All rights reserved. Mr. Momaday constructs beautifully cadenced sentences and summons a colorful assortment of stories and states of mind from a lively imagination. -- The New York Times Book Review, John Motyka