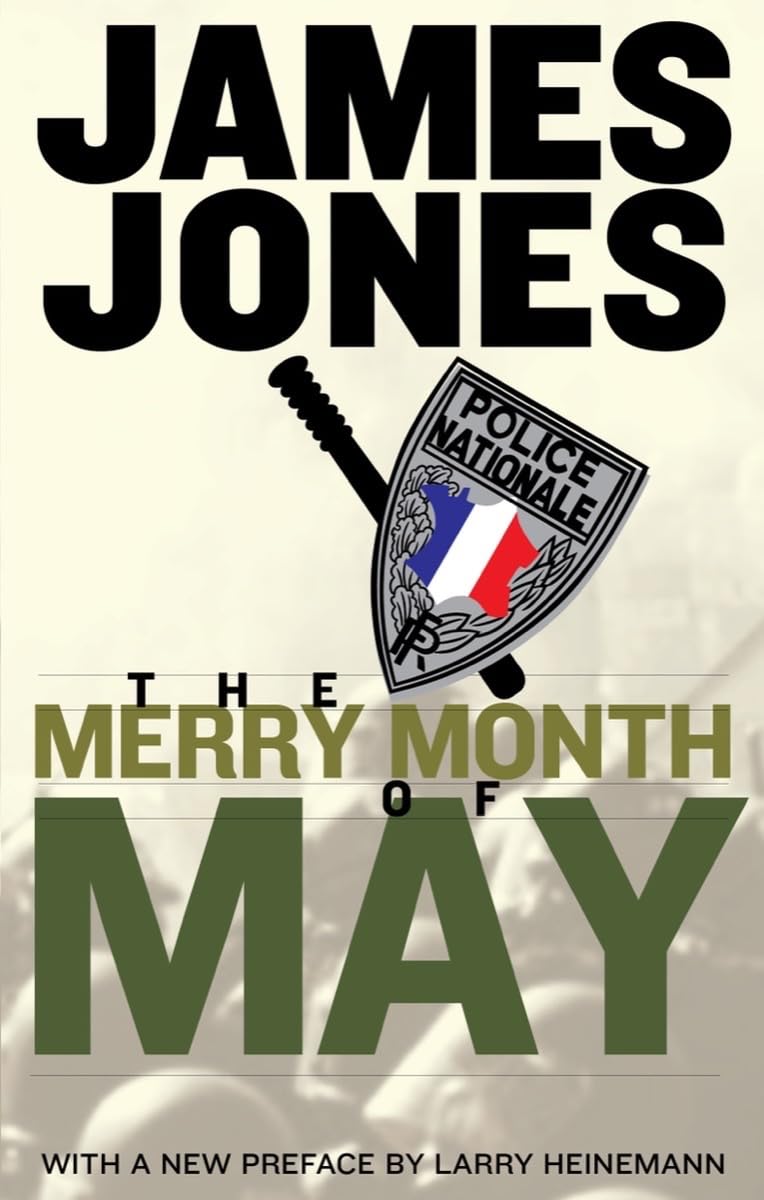

“Jones’s best novel after From Here to Eternity.” —Denver Post, Publishers Weekly, Library Journal, and others. “The only one of my contemporaries who I felt had more talent than myself was James Jones. And he has also been the one writer of any time for whom I felt any love.” —Norman Mailer Paris. May. 1968. This is the Paris of the barricaded boulevards; of rebelling students’ strongholds; of the literati; the sexual anarchists; the leftists—written chillingly of a time in French history that closely parallels what America went through in the late 1960s. As the Revolution sweeps across Paris, the reader sees, feels, smells, and fears all the turmoil that was the May revolt, the frightening social quicksand of 1968. "The only one of my contemporaries who I felt had more talent than myself was James Jones. And he has also been the one writer of any time for whom I felt any love." -- NORMAN MAILER Upon its initial publication in 1970, critics from the Denver Post, Publishers Weekly, Library Journal, and many other publications agreed that The Merry Month of May was Joness best novel since From Here to Eternity. Out of print for more than fifteen years, this edition includes a brand new preface by National Book Awardwinner Larry Heinemann (Pacos Story) and an introduction by Jones scholar Judith L. Everson. James Jones (1921-1977) established himself as one of the greatest American writers of the 20th century with his WWII trilogy, From Here to Eternity (National Book Award winner), The Thin Red Line, and Whistle. Excerpt from Chapter 1 WELL, IT'S ALL OVER. The Odéon has fallen! And today, which is June 16th, a Sunday, the police on orders of the Government entered and took over the Sorbonne on some unclear and garbled pretext about some man who was wounded by a knife. There was some rioting this afternoon, but the police handled it fairly easily. So that is it. And I sit here at my window on the river in the crepuscular light of that peculiar gray-blue Paris twilight which is so beautiful and like no other light anywhere on earth, and I wonder, What now? The sky is heavy and low tonight and this evening for the first time from the end of the Boulevard St.-Germain and the Pont Sully the tear gas reached us here on the almost sacrosanct Île St.-Louis. I finger my pen as I look out from my writing desk, and wonder if it is even worth it: the trying to put it down. M. Pompidou said, I remember, that "nothing in France would ever be the same again." Well, he was certainly right in regard to the Harry Gallaghers and their family. I am a failed poet, a failed novelist; quite probably I can be, and am, considered quite rightly to be a drop-out of a husband; why should I try? Even the desire isn't there any more. --And yet I feel I owe it to them. The Gallaghers. Only God knows what will happen to them now. And probably only I, of all the world, know what happened to them then--in the merry month of May. Most of all, I guess, I owe it to Louisa. Poor, dear, darling, straight-laced, mixed-up Louisa. I first met the Harry Gallaghers back in fifty-eight, ten years ago. I had just decided to stay on in Paris, and was going about the founding of my Review, The Two Islands Review. Failed poet, failed novelist, recently divorced, but still a man of an unquenchable literary bent, I felt there was the room in Paris for a newer English-language review. The Paris Review of then, despite its excellent "Art of Fiction" interviews, and the excellence of George's intentions, was fading away from the high standard it had declared itself dedicated to diffuse. I felt I could fill that gap. And, I did not look forward to returning to New York where although we had parted amicably enough, I would surely be forced by circumstances to see too much of my rich ex-wife at literary parties. I went around to see Harry Gallagher and some others to see if they would consent to become among my backers. I had met Harry, and knew that he had money: an income; one a great deal larger than my own. I also knew that Harry--though professionally a screenwriter--had always stood up for the arts. I thought he might be willing to put a little money into a new review with the intellectual and artistic standards I intended to give mine. Used Book in Good Condition