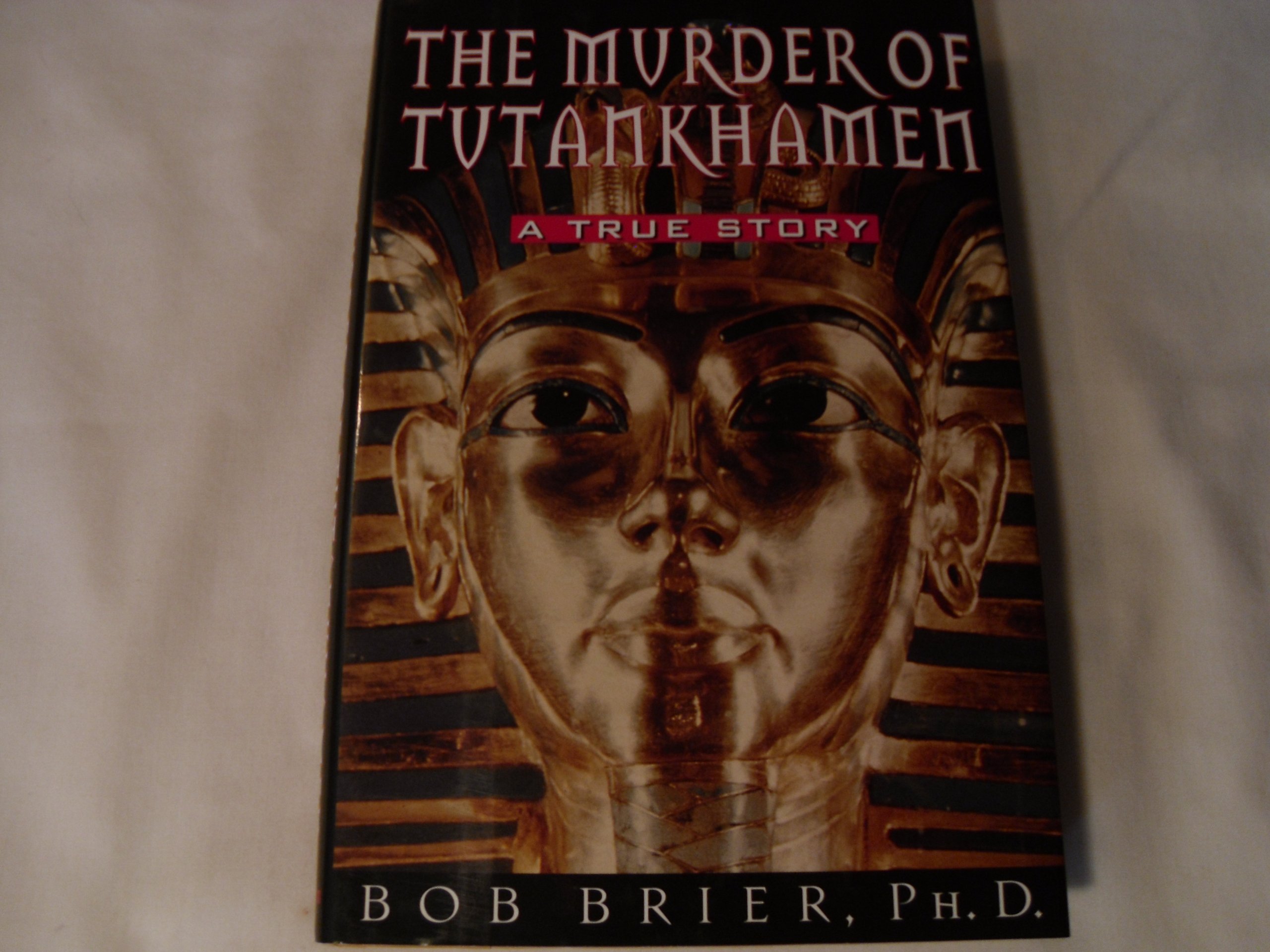

A startling look at the last days of the ancient Egyptian pharaoh draws on new medical and archaeological evidence that suggests that Tutankhamen suffered a brutal, untimely death that led to subsequent palace and political intrigue. 40,000 first printing. For decades after the discovery of Tutankhamen's tomb, the dazzling treasures found along with the mummy distracted many of us from the actual events of Tutankhamen's life. But take a look at the body itself--cranialX-rays reveal a location on the back of the skull that may indicate a hemorrhage, perhaps one caused by a deliberate blow. The question thus arises: Was King Tut murdered? Egyptologist Bob Brier specializes in paleopathology, the study of diseases in the ancient world. In essence, he performs high-tech autopsies on 3,000-year-old corpses. (He's also taken part in a re-creation of Egyptian mummification techniques, including the extraction of the brain through the nasal passages.) Here, he examines the X-rays and other photographic evidence, correlating it with the research of other Egyptologists, and concludes that Tutankhamen was the victim of political and religious intrigues that developed into a fatal conspiracy. True crime buffs and historians alike will find much to like in Brier's fast-paced recounting of his investigations. YA-Was Tutankhamen murdered? Brier presents his hypothesis in an engrossing tale that moves along at the pace of a well-crafted whodunit. In lucid prose, he gives the lay person an informative overview of Egyptian history prior to Tutankhamen's reign with special emphasis on his father, Amenhotep IV, who instituted the cult of Aten. As little is known about Tutankhamen's life, Brier reconstructs from wall paintings and hieroglyphic tablets and columns a perfectly plausible and fascinating picture of the boy-pharaoh's friendship with, then marriage to his half-sister Ankhesenamen and their daily life. Before reaching his 20th birthday, Tutankhamen died. His Grand Vizier, Aye, was named pharaoh, Ankhesenamen petitioned her sworn enemies, the Hittites, for a prince to become her consort, and this prince was killed en route to Egypt. A logical case is presented for murder: X rays of Tutankhamen's skull reveal what might be interpreted as a blow to his head; the Grand Vizier who succeeds the childless pharaoh wanted power; Ankhesenamen strangely disappeared after an arranged marriage to his successor. Brier obviously knows his subject and is impassioned by it. Readers who enjoy history or true-crime stories will be intrigued by this work. A detailed bibliography invites further reading. Helena Ferret, Chantilly Regional Library, VA Copyright 1998 Reed Business Information, Inc. Host of the Learning Channel's The Great Egyptians, Brier offers evidence that Tut was the victim of foul play. Copyright 1997 Reed Business Information, Inc. Can the truth be known about a possible murder that would have been committed 3,000 years ago? Respected Egyptologist Bob Brier, specialist in paleopathology (the study of diseases in the ancient world) and host of the Learning Channel's acclaimed series The Great Egyptians (to be broadcast in May), believes it can. Skillfully combining known historical events with evidence gathered by advanced technologies, Brier has re-created the suspenseful story of religious upheaval and political intrigue that likely resulted in the murder of the teenage king Tutankhamen. The lives and tumultuous times of Tutankhamen and his young bride, Ankhesenamen, are presented in historical context (Brier nicknames chapter 2 "Egypt 101"), providing an elemental understanding of the development of the three great powers of this era: military, priests, and king. Breathing life into old bones and artifacts, Brier examines all available evidence to arrive at "the most reasonable explanation for a tragic event," an explanation that, he says, is testable through the use of current technology on the mummified remains of the ancient king. Grace Fill In his eccentric but entertaining Egyptian Mummies (1994), Brier (Philosophy/C.W. Post Coll.) announced his intention to conduct a mummification of a human cadaver in the ancient manner. Here, after discussing the results of this grisly experiment, Brier uses his knowledge of ancient Egyptian mummification techniques and entombment practices to argue that the young King Tutankhamen (reigned 133323 b.c.) was murdered by his chief vizier, Aye. First Brier puts Tutankhamen's life in historical perspective by reconstructing the turbulent times in which he lived: A scion of the 18th Dynasty, Tutankhamen was the son of the great king Akhenaten, the monotheist who sought to destroy Egypt's traditional polytheistic religion. Succeeding to the throne as a child, Tutankhamen allowed the regent, Aye, to make the practical decisions of governance until he achieved adulthood. The traditional religion was restored, Akhenaten's memory was disgraced, and his religious innovation was br