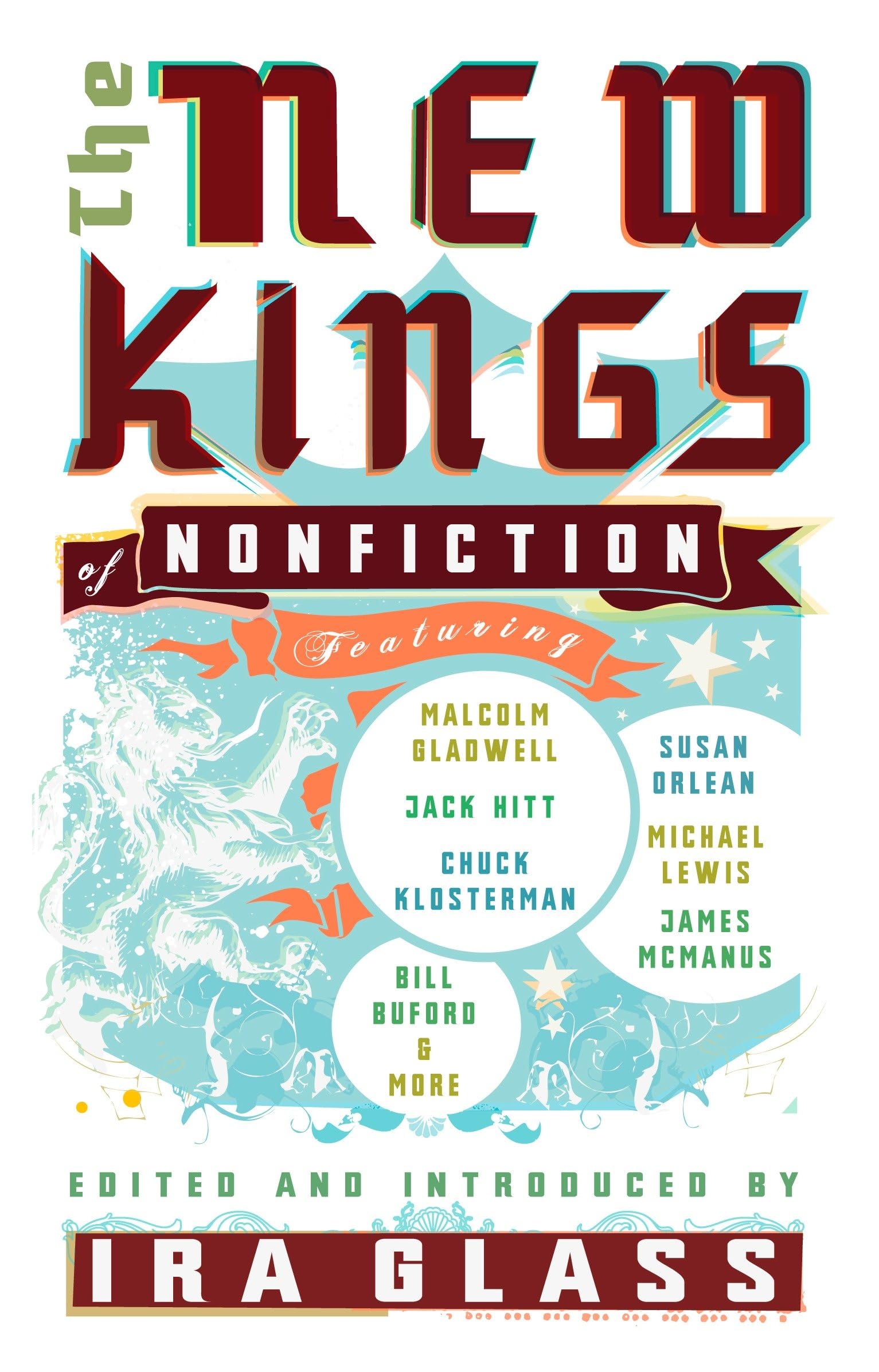

A collection of stories-some well known, some more obscure- capturing some of the best storytelling of this golden age of nonfiction. An anthology of the best new masters of nonfiction storytelling, personally chosen and introduced by Ira Glass, the producer and host of the award-winning public radio program This American Life . These pieces-on teenage white collar criminals, buying a cow, Saddam Hussein, drunken British soccer culture, and how we know everyone in our Rolodex-are meant to mesmerize and inspire. Ira Glass is the producer and host of the award-winning radio and television program "This American Life". Introduction Years ago, when I worked for public radio’s daily news shows, I put together this story about a guy named Jack Davis. He was a Rush Limbaugh fan and a proud Republican, and he’d set out on an unusual mission. He wanted to go into the Chicago public housing projects to instruct the children there in the value of hard work and entrepreneurship. He’d do this with vegetables. His plan was to teach the kids at the Cabrini Green projects to grow high-end produce, they’d sell their crop to the fancy restaurants that are just blocks from Cabrini, and this would be a valuable life lesson in the joys of market capitalism. So Jack set up a garden in the middle of the high-rises, and for the first few years, it didn’t go so well. Jack was an accountant from the white suburbs and he didn’t relate to the kids or understand the culture of the projects. He made a lot of parents mad. A kid would miss a day’s work in the vegetable garden and Jack would dock his pay, to teach the consequences of sloth. Then all the windows in Jack’s truck would get smashed. Jack’s message was not getting through. Hoping to turn this around, he enlisted this guy named Dan Underwood, who lived in Cabrini and whose children had been working in the garden. Everyone in the projects seemed to know Dan. He ran a double-Dutch jump-rope team for Cabrini kids that was ranked number one in the city, and a drum and color-guard squad, and martial arts classes. Kids loved Dan. He was fatherly. He was fun. And while Jack was committed to the idea that they should run the vegetable garden like a real business, Dan saw it as just another afterschool program. “These are children,” he told me. “It’s not like an adult coming to work at, you know, 8:00 and getting off at 4:30, and ‘If you don’t come, you don’t get no money.’ That won’t work, not with a child.” When a kid didn’t show up to pick tomatoes, Dan would go to the family and find out why. He’d buy the kids pizza and take them on trips and get them singing in the van. What they needed was no mystery, as far as he was concerned. They were normal kids growing up in an unusually tough neighborhood, and they needed what any kid needs: some attention and some fun. And sometimes, when he and Jack argued over how to run the program, they were both aware—uncomfortably aware, I think—how they were reenacting, in a vegetable garden surrounded by dingy high-rises, a bigger national debate. The white suburbanite was stomping around insisting that the project kids get a job and show up on time and not be coddled anymore, all for their own good, all to make them self-sufficient. The black guy was telling the interloper that he didn’t know what he was talking about. A little coddling might be better for these kids than an enhanced appreciation of the work ethic and the free market. When I was working on this story I thought that Jack and Dan would’ve made a great ’70s TV show, one of those Norman Lear sitcoms where every week something happens to make all the characters argue about the big issues of the day. Sadly, we were twenty years too late for that, and Norman Lear had already set a show— Good Times —in Cabrini Green. One interesting thing about this story was how my officemate at the time hated it. Or maybe hate ’s too strong a word. He was suspicious of the story. And he was incredulous at how it seemed to lay out like a perfect little fable about modern America. “Are you making these stories up?” I remember him asking. But I don’t see anything wrong with a piece of reporting turning into a fable. In fact, when I’m researching a story and the real-life situation starts to turn into allegory—as it did with Dan and Jack—I feel incredibly lucky, and do everything in my power to expand that part of the story. Everything suddenly stands for something so much bigger, everything has more resonance, everything’s more engaging. Turning your back on that is rejecting tools that could make your work more powerful. But for a surprising number of reporters, the stagecraft of telling a story—managing its fable-like qualities—is not just of secondary concern, but a kind of mumbo jumbo that serious-minded people don’t get too caught up in. Taking delight in this part of the job, from their perspective, has little place in our important work as journalists. Another public radio officemate at