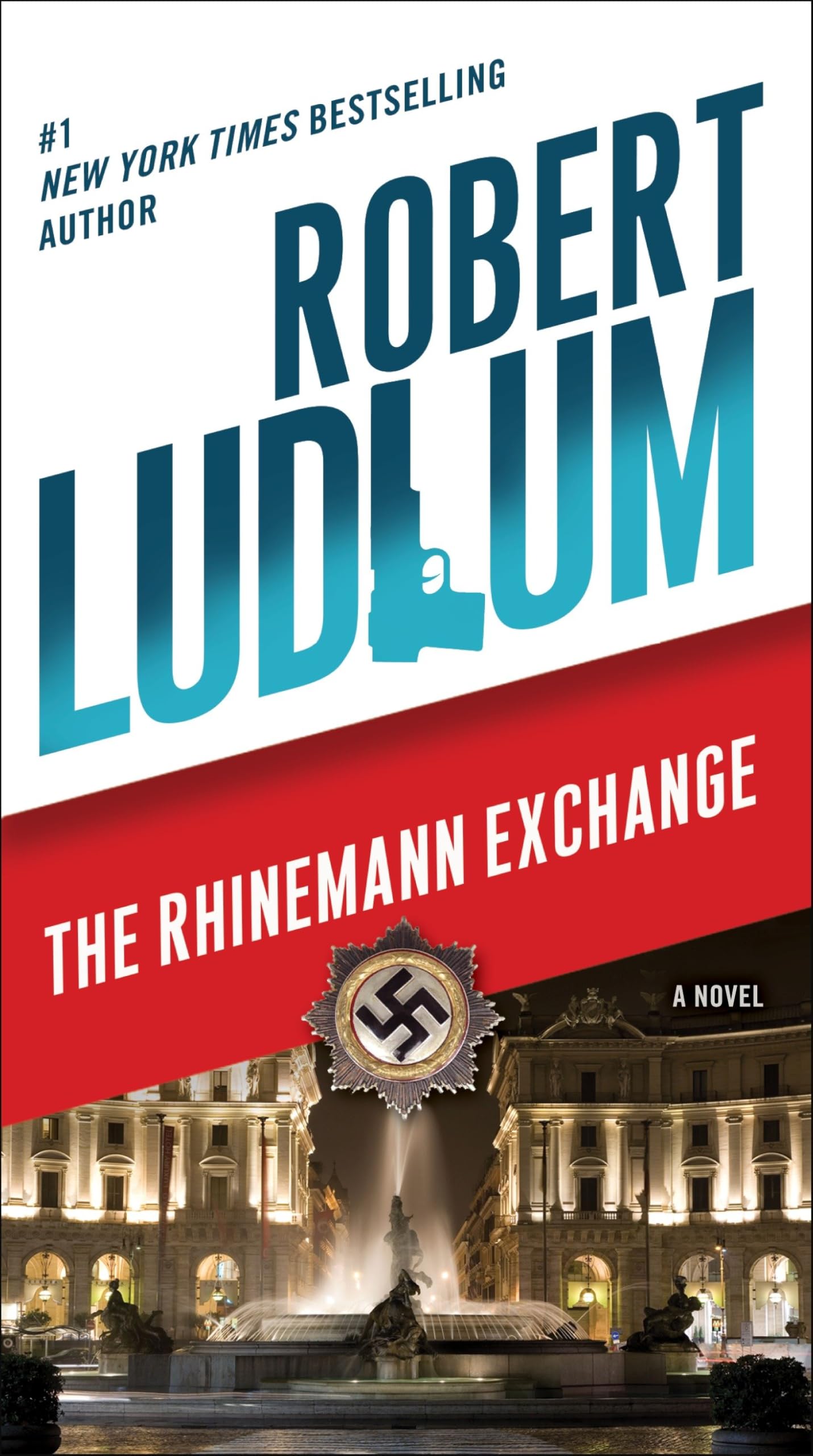

Autumn 1943. American agent David Spaulding is among the global espionage elite who have converged on Buenos Aires. His top-secret mission can bring World War II to an explosive end. But what happens in this city of assassins, betrayals, and sensual encounters is the most sinister and terrifying deal ever made between two nations. Intense, high-level covert negotiations will soon bear dangerous fruit with the aid of expatriate German industrialist Erich Rhinemann. But suddenly the game changes, and Spaulding is the man caught in the middle. Struggling furiously to save his sanity, the woman he loves, and his very life, Spaulding might be the only one who can rescue the world from a shattering fate. Praise for Robert Ludlum and The Rhinemann Exchange “A superb plot filled with exciting chases, double crosses, secret codes, and beautiful women . . . a picture of the beastliness underlying the espionage world, a world of brilliance without scruples, brutality without restraint.” — Chicago Tribune “A breathtaking pace . . . The plot is extraordinary.” — Bestsellers “A paragon in the field.” — The New York Times Praise for Robert Ludlum and The Rhinemann Exchange “A superb plot filled with exciting chases, double crosses, secret codes, and beautiful women . . . a picture of the beastliness underlying the espionage world, a world of brilliance without scruples, brutality without restraint.” — Chicago Tribune “A breathtaking pace . . . The plot is extraordinary.” — Bestsellers “A paragon in the field.” — The New York Times Robert Ludlum was the author of twenty-one novels, each a New York Times bestseller. There are more than 210 million of his books in print, and they have been translated into thirty-two languages. In addition to the Jason Bourne series— The Bourne Identity, The Bourne Supremacy, and The Bourne Ultimatum —he was the author of The Scarlatti Inheritance, The Chancellor Manuscript, and The Apocalypse Watch, among many others. Mr. Ludlum passed away in March 2001. 1 September 10, 1943, Berlin, Germany Reichs-minister of Armaments Albert Speer raced up the steps of the Air Ministry on the Tiergarten. He did not feel the harsh, diagonal sheets of rain that plummeted down from the grey sky; he did not notice that his raincoat—unbuttoned—had fallen away, exposing his tunic and shirt to the inundation of the September storm. The pitch of his fury swept everything but the immediate crisis out of his mind. Insanity! Sheer, unmitigated, unforgivable insanity! The industrial reserves of all Germany were about exhausted; but he could handle that immense problem. Handle it by properly utilizing the manufacturing potential of the occupied countries; reverse the unmanageable practices of importing the labor forces. Labor forces? Slaves! Productivity disastrous; sabotage continuous, unending. What did they expect? It was a time for sacrifice! Hitler could not continue to be all things to all people! He could not provide outsized Mercedeses and grand operas and populated restaurants; he had to provide, instead, tanks, munitions, ships, aircraft! These were the priorities! But the Führer could never erase the memory of the 1918 revolution. How totally inconsistent! The sole man whose will was shaping history, who was close to the preposterous dream of a thousand-year Reich, was petrified of a long-ago memory of unruly mobs, of unsatisfied masses. Speer wondered if future historians would record the fact. If they would comprehend just how weak Hitler really was when it came to his own countrymen. How he buckled in fear when consumer production fell below anticipated schedules. Insanity! But still he, the Reichs-minister of Armaments, could control this calamitous inconsistency as long as he was convinced it was just a question of time. A few months; perhaps six at the outside. For there was Peenemünde. The rockets. Everything reduced itself to Peenemünde! Peenemünde was irresistible. Peenemünde would cause the collapse of London and Washington. Both governments would see the futility of continuing the exercise of wholesale annihilation. Reasonable men could then sit down and create reasonable treaties. Even if it meant the silencing of un reasonable men. Silencing Hitler. Speer knew there were others who thought that way, too. The Führer was manifestly beginning to show unhealthy signs of pressure—fatigue. He now surrounded himself with mediocrity—an ill-disguised desire to remain in the comfortable company of his intellectual equals. But it went too far when the Reich itself was affected. A wine merchant, the foreign minister! A third-rate party propagandizer, the minister of eastern affairs! An erstwhile fighter pilot, the overseer of the entire economy ! Even himself. Even the quiet, shy architect; now the minister of armaments. All that would change with Peenemünde