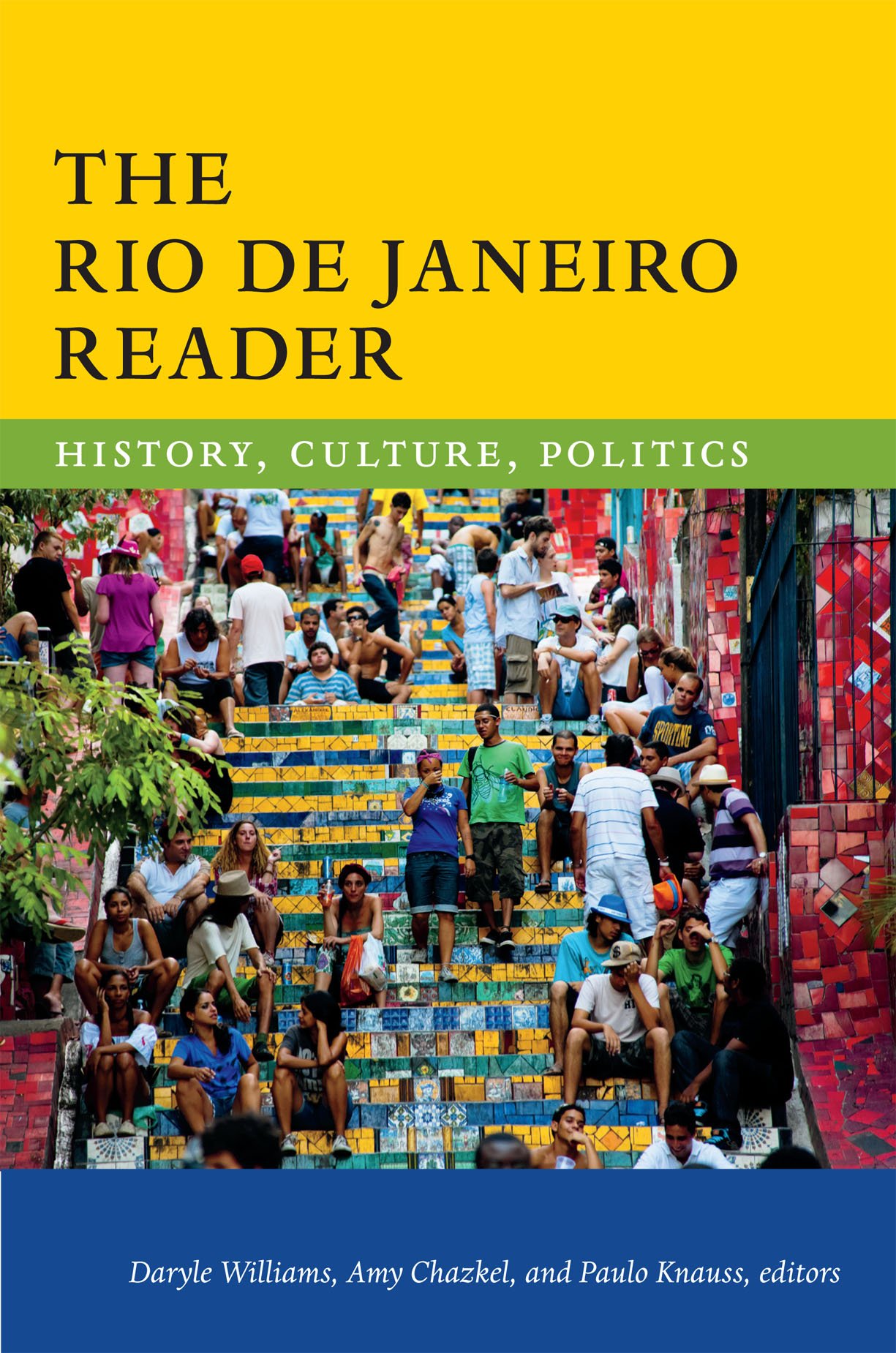

The Rio de Janeiro Reader: History, Culture, Politics (The Latin America Readers)

$22.63

by Daryle Williams

Shop Now

Spanning a period of over 450 years, The Rio de Janeiro Reader traces the history, culture, and politics of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, through the voices, images, and experiences of those who have made the city's history. It outlines Rio's transformation from a hardscrabble colonial outpost and strategic port into an economic, cultural, and entertainment capital of the modern world. The volume contains a wealth of primary sources, many of which appear here in English for the first time. A mix of government documents, lyrics, journalism, speeches, ephemera, poems, maps, engravings, photographs, and other sources capture everything from the fantastical impressions of the first European arrivals to the complaints about roving capoeira gangs, and from sobering eyewitness accounts of slavery's brutality to the glitz of Copacabana. The definitive English-language resource on the city, The Rio de Janeiro Reader presents the "Marvelous City" in all its complexity, importance, and intrigue. " The Rio Reader is an excellent source of materials for the classroom in all the multiple fields of urban history from a social, political, economic, or cultural perspective. They would come handy on any course focusing on global history, the Black Atlantic, port cities, planning history (in addition to courses on Latin American history in general). Even more, the book is a perfect companion for a visit to Rio de Janeiro: it triggers a truly historical imagination to unpack a city in which past and present form a chaotic amalgam." -- Leandro Benmergui ― Planning Perspectives "Prepared by three leading Rio de Janeiro scholars, The Rio de Janeiro Reader offers a sweeping and in-depth exploration of the city. Lively and interesting, it provides a gateway into understanding the social, economic, political, and cultural diversity of the city over the last 500 years." -- James N. Green, author of ― We Cannot Remain Silent: Opposition to the Brazilian Military Dictatorship in the United States Daryle Williams is Associate Professor of History at the University of Maryland and the author of Culture Wars in Brazil: The First Vargas Regime, 1930–1945 , also published by Duke University Press. Amy Chazkel is Associate Professor of History at the City University of New York, Queens College and the CUNY Graduate Center, and the author of Laws of Chance: Brazil's Clandestine Lottery and the Making of Urban Public Life , also published by Duke University Press. Paulo Knauss is Professor of History at Universidade Federal Fluminense (Niterói, Brazil) and the author of Rio de Janeiro da pacificação: Franceses e portugueses na disputa colonial . The Rio de Janeiro Reader History, Culture, Politics By Daryle Williams, Amy Chazkel, Paulo Knauss Duke University Press Copyright © 2016 Duke University Press All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-8223-6006-3 Contents A Note on Translations, Spelling, and Monetary Units, Place-Names and Way-Finding, Acknowledgments, Introduction: The Marvelous City, I Colonial Rio, II Imperial Rio, III Republican Rio, IV Recent Rio, Suggestions for Further Reading and Viewing, Acknowledgment of Copyrights and Sources, Index, CHAPTER 1 Colonial Rio The history of Rio de Janeiro as a European colonial city begins in the sixteenth century. A human history of the region, however, begins earlier. A variety of allied Tupi-speaking clans, living in small villages situated among subtropical forests and wetlands, settled the region of southeastern Brazil that would give rise to a world metropolis that the Portuguese named São Sebastião do Rio de Janeiro (Saint Sebastian of Rio de Janeiro). Numbering more than fifteen thousand at the turn of the sixteenth century, the Tamoios lived on the shores and islands of Guanabara Bay. These native peoples hunted, fished, and cultivated manioc, beans, and peanuts in cleared woodlands. Their human footprint produced substantial secondary-growth forests. Although indigenous Rio was not physically or spiritually "conquered" along the lines of Aztec Tenochtitlán and Inca Cuzco, Portuguese mariners and clerics, alongside other Europeans, aspired to dominate and Christianize the natives and their lands. The outsiders' demands for brazilwood exacted a heavy toll on the landscape and its indigenous peoples. War and epidemic disease caused substantial disruption to Tamoio lifeways. In the hinterlands, thousands of Indian or other ethnic groups were forcibly settled in villages ( aldeamentos ), where they could be more easily overseen and converted to Catholicism. Many were periodically drafted into Rio's early colonial labor market. The large bay that Europeans initially mistook for the mouth of a great river gave the future city its curious name, Rio de Janeiro (River of January). That name stuck as an artifact of the misapprehension typical of the colonial enterprise in the Americas. Significantly, a variant of Tupian terms for "sea" also stuck,