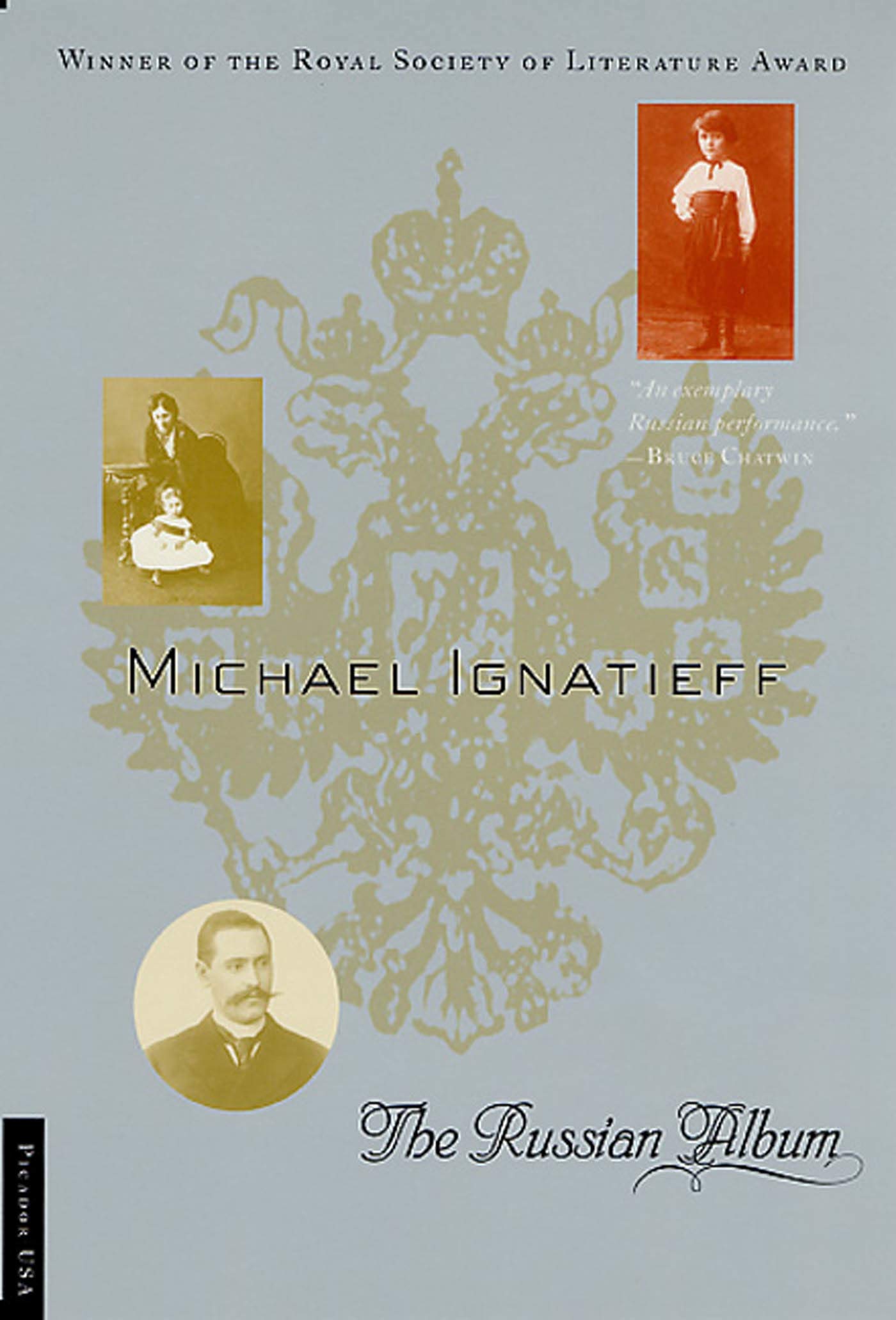

Winner of the Royal Society of Literature Award In The Russian Album , Michael Ignatieff chronicles five generations of his Russian family, beginning in 1815. Drawing on family diaries, on the contemplation of intriguing photographs in an old family album, and on stories passed down from father to son, he comes to terms with the meaning of his family's memories and histories. Focusing on his grandparents, Count Paul Ignatieff and Princess Natasha Mestchersky, he recreates their lives before, during, and after the Russian Revolution. “A vividly fascinating account by a gifted writer who sweeps back the curtain from the past, revealing it full of color and life.” ― Suzanne Massie, The New York Times Book Review “A rich story of a cultivated elite bound to a disintegrating autocracy.” ― Walter Goodman, The New York Times “ The Russian Album is a poignant family memoir, a fitting close to Russian life before the 'red curtain of the revolution.'” ― Elena Brunet, Los Angeles Times “A vivid, fascinating account by a gifted writer who sweeps back the curtain from the past, revealing it full of color and life.” ― New York Times “Spellbinding...a family history, focusing on the author's grandparents who fled with their young sons from the Russian Revolution . . . But this is more than a family memoir. It's a meditation on rootlessness and belonging, and on the ambivalent feelings we all have about the lost past and about our forbears. Not to be missed.” ― Victoria Glendinning, Vogue “An exemplary Russian performance.” ― Bruce Chatwin “ The Russian Album is a work of such evocative power that the story of one family will speak volumes to many.” ― Maclean's “ The Russian Album is a joy to read. Every sentence seems heartfelt. And the book as a whole is likely to captivate all who are interested in the question of roots.” ― Cleveland Plain Dealer “This beautifully written book . . . is about tenderness, courage, and a sublime life-force.” ― The Observer (London) Michael Ignatieff is the author of Isaiah Berlin and The Warrior’s Honor , as well as over fifteen other acclaimed books, including a memoir, The Russian Album, and the Booker finalist novel Scar Tissue . He writes regularly for the New York Times , the New York Review of Books , and the London Review of Books . Former head of Canada’s Liberal Party, director of the Carr Center for Human Rights at Harvard’s Kennedy School, and president of Central European University, he is currently a professor at CEU in Vienna. The Russian Album By Michael Ignatieff Picador Copyright © 1997 Michael Ignatieff All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-312-28183-0 Contents TITLE PAGE, COPYRIGHT NOTICE, ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS, DEDICATION, IGNATIEFF AND MESTCHERSKY FAMILY TREE, 1. THE BROKEN PATH, 2. MOTHER AND DAUGHTER, 3. FATHER AND SON, 4. PAUL AND NATASHA, 5. PETROGRAD, 6. REVOLUTION, 7. THE CAUCASUS, 8. SAVAGE LANDS AFAR, 9. THE LITTLE FOOLS, AFTERWORD, INDEX, ALSO BY MICHAEL IGNATIEFF, COPYRIGHT, CHAPTER 1 THE BROKEN PATH Dwell on the past and you'll lose an eye. Ignore the past and you'll lose both of them. OLD RUSSIAN PROVERB No one I know lives in the house where they grew up or even in the town or village where they once were children. Most of my friends live apart from their parents. Many were born in one country and now live in another. Others live in exile, forming their thoughts in a second language among strangers. I have friends whose family past was consumed in the concentration camps. They are orphans in time. This century has made migration, expatriation and exile the norm, rootedness the exception. To come as I do from a hybrid family of White Russian exiles who married Scottish Canadians is to be at once lucky – we survived – and typical. Because emigration, exile and expatriation are now the normal condition of existence, it is almost impossible to find the right words for rootedness and belonging. Our need for home is cast in the language of loss; indeed, to have that need at all you have to be already homeless. Belonging now is retrospective rather than actual, remembered rather than experienced, imagined rather than felt. Life now moves so quickly that some of us feel that we were literally different people at previous times in our lives. If the continuity of our own selves is now problematic, our connection with family ancestry is yet more in question. Our grandparents stare out at us from the pages of the family album, solidly grounded in a time now finished, their lips open, ready to speak words we cannot hear. For many families, photographs are often the only artefacts to survive the passage through exile, migration or the pawnshop. In a secular culture, they are the only household icons, the only objects that perform the religious function of connecting the living to the dead and of locating the identity of the living in time. I never feel I know my friends until either I meet their p