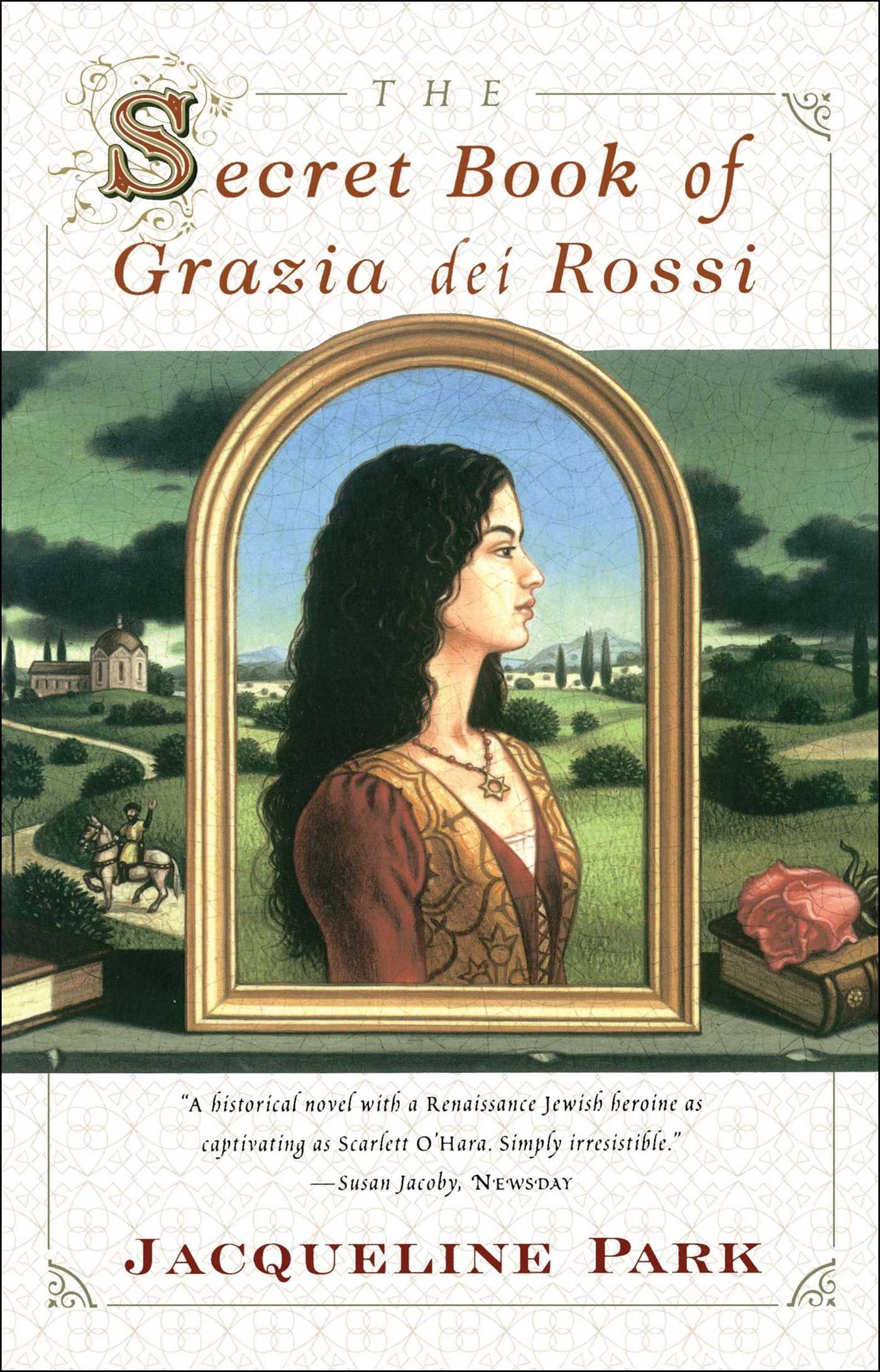

The Secret Book of Grazia dei Rossi is a sweeping tale of intrigue and romance set in a time rife with court politics, papal chicanery, religious intolerance, and inviolable social rules. Grazia, private secretary to the world-renowned Isabella d'Este, is the daughter of an eminent Jewish banker, the wife of the pope's Jewish physician, and the lover of a Christian prince. In a "secret book," written as a legacy for her son, she records her struggles to choose between the seductions of the Christian world and a return to the family, traditions, and duties of her Jewish roots. As she re-creates Renaissance Italy in captivating detail, Jacqueline Park gives us a timeless portrait of a brave and brilliant woman trapped in an unforgiving, inflexible society. Susan Jacoby Newsday A historical novel with a Renaissance Jewish heroine as captivating as Scarlett O'Hara. Simply irresistible. Chris Ledbetter Detroit Free Press An epic book...Park's picture of the Renaissance is as incandescent as Italy's frescoes. Marylin Chandler McEntyre San Francisco Chronicle Book Review One is reluctant to close this window on a dramatic chapter of the distant past, or to part company with a woman so full of grace and gumption. Elizabeth Renzetti The Toronto Globe and Mail A sprawling historical novel that boasts its research on every page. Sharon Kay Penman author of The Queen's Man A remarkable book. Grazia is an unforgettable character. Sue Miron The Miami Herald Wonderful. An absolutely fascinating, compulsively readable novel about a sixteen-century woman who would be considered outstanding in any era. Jacqueline Park is the founding chairman of the Dramatic Writing Program and professor emerita at New York University's Tisch School of the Arts. Born and educated in Canada, she now lives in New York, Toronto, and Miami Beach. Chapter One I will begin on holy Thursday in the Christian year 1487, Eastertide for the Christians, Passover for the Jews, a perilous time for all. Until that day I had lived the eight years of my life in a child's paradise. On Passover eve Fra Bernardino da Feltre preached an Easter sermon in the town of Mantova. After that day nothing was ever the same again. The day began for me and my little brother in the ordinary way. Awakened at cock's crow by the slave girl Cateruccia, who slept at the foot of our bed, we washed up, said our prayers, and went on to Mama's room for a sweet bun and some watered wine. This repast had been added to the household routine the year before on the advice of the humanist physician Helia of Cremona. According to him a small amount of bread and wine at the beginning of the day gave protection against the plague by heating the stomach, thus strengthening it against disease. Since few of our neighbors ever served a morsel of food until dinnertime, this extra meal gave our famiglia a certain notoriety among those whose minds and habits were mired in the Dark Ages. But our parents were adherents of all things modern and humanistic. They believed in the superiority of the ancients, the beauty of the human body, and the new educational methods of Maestro Vittorino. Not for them the rabbinical axiom "First the child is allured; then the strap is laid upon his back." Our tutor was never permitted to use the rod. Out of respect to the wisdom of the ancients, daily exercise was as faithfully adhered to as daily prayers. Mens sana in corpore sano. Even on Passover eve, we made our daily pilgrimage to the Gonzaga stud where our family had permission to ride, Jehiel and I on our pony, Papa on a black Araby stallion looking every bit the great lord in his sable-trimmed cloak. We often saw the young Marchese, Francesco Gonzaga, gallop by although he rarely troubled himself to acknowledge us. However, that morning he stopped to have a private word with Papa, whom he called Maestro Daniele, a term of some respect. It was not a long audience. Francesco Gonzaga always preferred to converse with dogs and horses rather than people. But his demeanor that day was remarkably agreeable. He even had a smile for us. I thought he must be amused by the way we rode our pony, I in the saddle and Jehiel on pillion, contrary to the usual arrangement for boys and girls. Whatever his reasons, to me it was as if one of the gods had descended from heaven and smiled on us. I didn't even notice how ugly he was. To my surprise, Papa introduced Jehiel to the Marchese by the name Vitale. I now know that Vitale is what Christians call all Jews named Jehiel, in the odd belief that they are translating the name directly from Hebrew into Italian, since Jehiel means "light" in Hebrew and Vitale means "light" in the Italian vernacular. My name, as is almost always the case with women, remains Grazia to both Jews and Christians. Apparently precise distinctions are not necessary in the naming of girls. As for Jehiel, he was as perplexed to hear himself called Vitale as I. I think my brother h