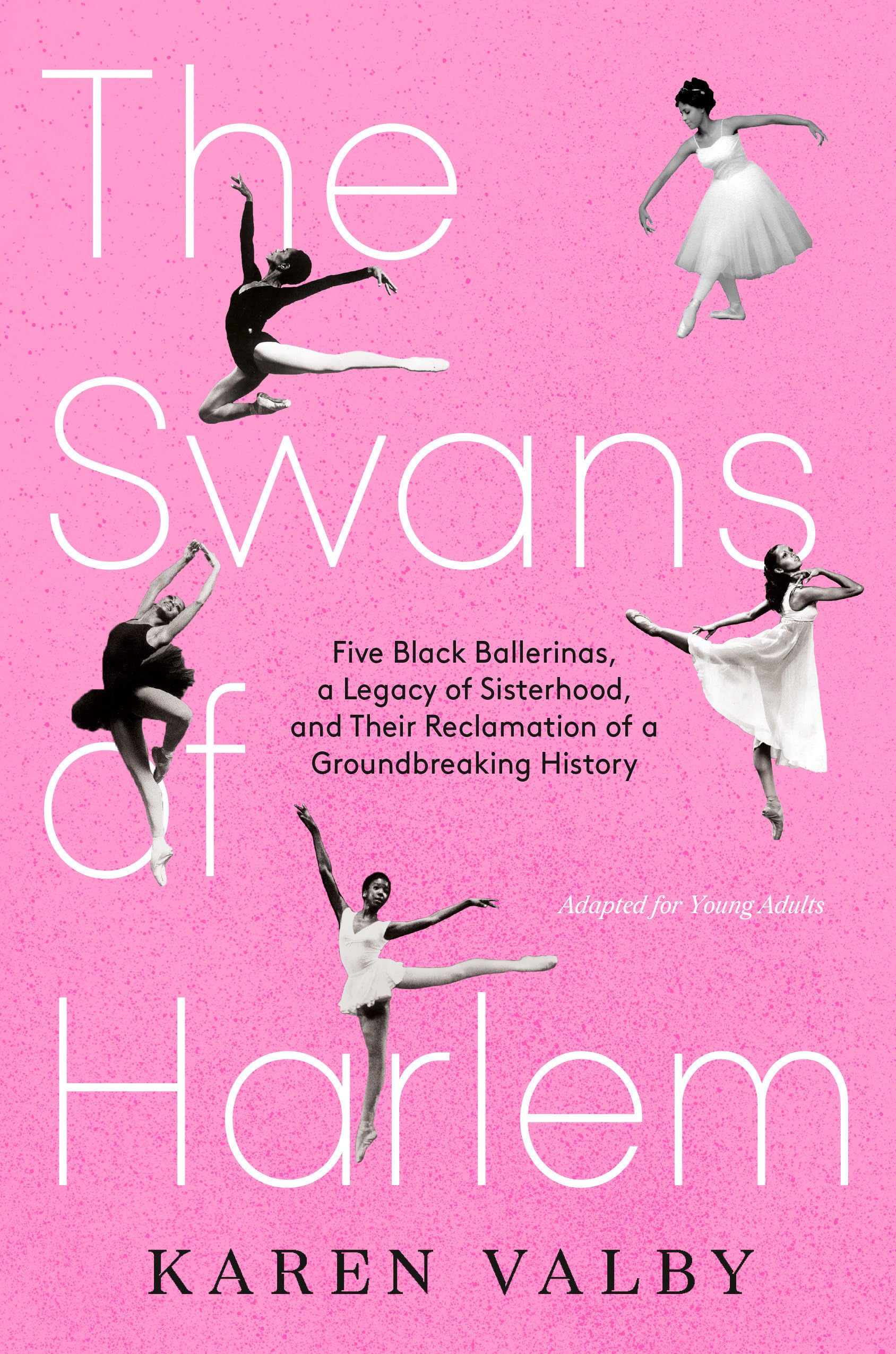

The Swans of Harlem (Adapted for Young Adults): Five Black Ballerinas, a Legacy of Sisterhood, and Their Reclamation of a Groundbreaking History

$12.99

by Karen Valby

Shop Now

In this young adult adaptation of Karen Valby's adult non-fiction title, you'll meet five amazing Black ballerinas from The Dance Theater of Harlem, including some of the founding members, who broke barriers and made history in the world of classical dance, at a time when racism shut out Black dancers from major dance companies. At the peak of the civil rights movement, Lydia Abarca was the first ballerina in a Black ballet company to grace the cover of Dance magazine. Alongside founding members Shelia Rohan and Gayle McKinney-Griffith and first-generation dancers Karlya Shelton and Marcia Sells, Abarca invited a bright light to shine on Black professional classical dancers. Grit, determination, and exquisite artistry propelled these swans of Harlem to dizzying heights as they performed around the world for audiences that included celebrities, dignitaries, and royalty. Now, decades later, these trailblazing ballerinas and longtime friends are giving voice to their stories on- and offstage, reclaiming their past so that it is finally recorded, acknowledged, and lauded, never to be lost again. ★ "This powerful account is part cultural history, part biography as it traces the formation, rise, and decline of DTH through the experiences of these five ballerinas, as well as their continued importance to dancers of color today.... this will appeal equally to fans of forgotten histories. " — Booklist , starred review " A poignant and gripping piece of little-known history." — Kirkus Reviews " [A] thoughtfully crafted piece of narrative nonfiction." — The Bulletin Karen Valby is the author of two books of nonfiction: The Swans of Harlem and Welcome to Utopia: Notes from a Small Town. A contributing editor for Vanity Fair, she also writes for the New York Times, O Magazine, Glamour, Fast Company, and EW, where she spent fifteen years writing about culture . She and her family live in Austin, Texas, where her daughters study dance at Ballet Afrique. 1 Harlem kids lived in a world of their own making. Not on the busy avenues like Broadway or Amsterdam, but on the quieter side streets, where there was more freedom. They played double Dutch and jacks and stickball. They hit the local play-ground, the Battlegrounds, for the monkey bars and swings, and for hoops if they could hold their own. They played street games, like the tag game Ringolevio or Hot Peas and Butter, in which the leader hid a belt behind a stoop or a trash can and then yelled out to the others, “Hot Peas and Butter, come and get your sup-per!” They were kids with parents who expected them back inside when the streetlights came on and neighbors who looked down from open windows with chins in hands, ready to pull them out of trouble by their ears. Kids who knew when someone’s older brother or cousin had started sniffing glue or trying heroin and would learn to avoid them when they got to acting like strangers. Kids who’d lived through six days of rioting in their neighborhoods in 1964, as people took to the streets to pro-test the murder of a fifteen-year-old Black boy who had been gunned down by a white police officer in front of his friends and a dozen witnesses. And kids who lived, too, through the awful spring of 1968, when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered on the balcony of a second-floor Memphis motel room, just a few days before he was set to join a march on behalf of striking sanitation workers. When news of King’s death rained down upon Harlem, Lydia Abarca was seven-teen. She remembers her mother, Josephine, crying at their kitchen table. “What are we going to do now?” her mother said. “They killed this one hope.” But two months after Dr. King’s murder, one of Abarca’s five sisters came home from her violin classes with ground-shifting news: “Lydia, they’ve got a Black man up there. He’s going to be teaching ballet.” Sandra, seven years Lydia’s junior, had seen a flyer at Harlem School of the Arts, which was run out of the basement of the St. James Presbyterian Church on 141st Street and St. Nicholas. Somebody named Arthur Mitchell was starting a ballet program for kids in the neighborhood, and he wanted grown dancers too. Lydia Abarca had let ballet go when she was fifteen, tired of giving her whole self over to something that never seemed to love her back. When she heard about Ar-thur Mitchell’s new school, she’d just graduated high school and was headed on a partial scholarship to Fordham University in the fall. She was going to be the first Abarca to go to college--Josephine liked to think her baby could be a doctor--and in the meantime, she needed to make a little money working a summer job as a sec-retary in the lobby at a bank down the street from their projects. Monday through Friday, she’d rotate through her same three outfits--twelve years in a Catholic school uniform doesn’t build an impressive wardrobe--for a paycheck doing work she hated and wasn’t especially good at. When her sister told her about th