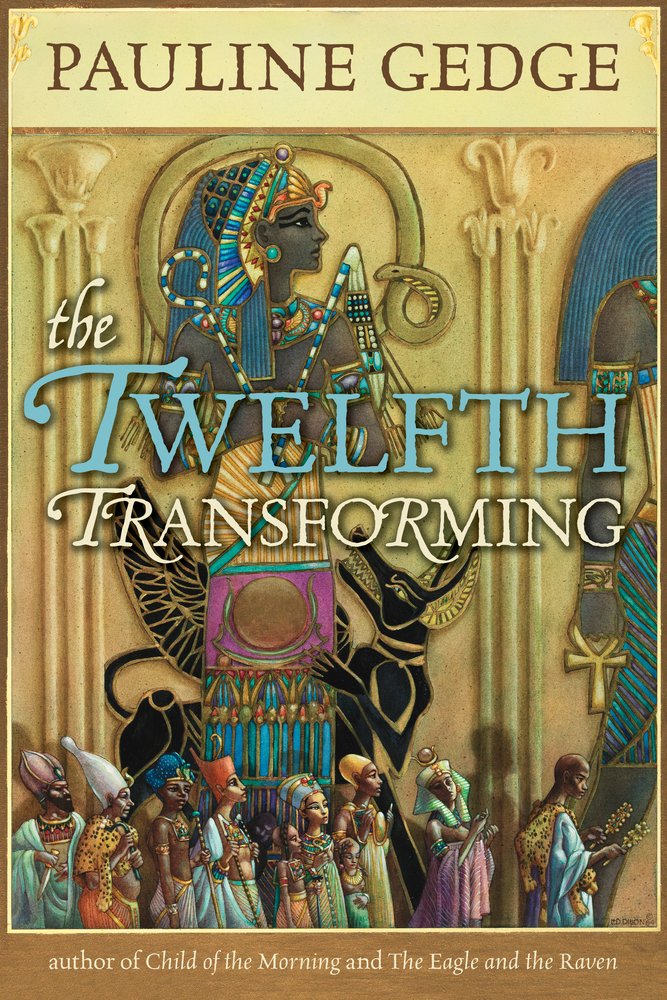

In The Twelfth Transforming , bestselling author Pauline Gedge returns to ancient Egypt to reveal the mysterious reign of Akhenaten, the impetuous pharaoh who threatened to ruin his country. The dramatic story of Akhenaten’s disastrous ruling is also the tale of Empress Tiye, a mother struggling to save her land from the catastrophe of her son’s choices. Gedge’s vivid descriptions of imperial court life among the lushness of the Nile and the desiccation of the desert lands will enthrall readers seeking an evocative tale of power, dynasty, family and curses, all set in the enchanting world of ancient Egypt. “Stunning realism . . . a multicolored tapestry.” — Publishers Weekly “A beautifully detailed historical biography in the tradition of Mary Renault . . . a sensuous, teeming, complex world of intrigue and passion.” — San Francisco Chronicle “A lustrous tale about Pharaonic decadence, told not in strident, panoramic fashion, but in the quiet undertone of an intimate chronicle. . . . A sad and often lyrical narrative of a self-centered family’s corruption and downfall. [Gedge] tells it truthfully, if slowly, convincing the reader that inhabitants of an alien culture with improbable mores remain painfully human, that fundamentals endure.” — New York Times Book Review “Blends impeccable historical research with superb fiction . . . draws the readers completely into the splendor and pageantry of a rich and complex civilization [with] a cast of characters so memorable that they seem to breathe on every page.” — Cleveland Plain Dealer “Makes ancient Egypt come alive. . . . Historical fiction at its best.” — Daily Oklahoman CA The Twelfth Transforming By Pauline Gedge Chicago Review Press Incorporated Copyright © 1984 Pauline Gedge All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-912777-29-0 CHAPTER 1 The empress Tiye left her quarters escorted by four Followers of His Majesty and her chief herald. Beneath the torches that lined the passage between her chamber and the garden doors stood the palace guards, scimitars sheathed in leather scabbards, white kilts and blue and white leather helmets cool and startling against brown skin. As she passed, spears were thrust forward and heads bowed. The garden lay unlit, the smothering darkness untouched by the desert stars that flared overhead. The little company paced the paths briskly, paused, were admitted through the dividing wall into Pharaoh's own acres, and passed along the rear wall of the palace. Outside the tall double doors from which Pharaoh often issued to walk in his garden or stand and gaze at the western hills, Tiye ordered her escort to wait, and she and the herald plunged into the passageway beyond. As she walked, her glance, always drawn to the confusion of painted images on the walls, moved up to the frieze under the line of the ceiling. Pharaoh's throne name, inscribed in gold leaf set in fragrant cedar from Amki, was repeated continuously. Nebmaatra: The Lord of Truth is Ra. There was nowhere in all the acres the palace covered where one could go to escape from the words. Tiye came to a halt, and Pharaoh's steward, Surero, rose from his seat by the door and prostrated himself. "Surero, please announce to His Majesty that the Goddess of the Two Lands is waiting," her herald said, and Surero disappeared, emerging moments later to bow Tiye into the room. Her herald settled on the floor of the passage, and the doors were closed behind her as she walked forward. Pharaoh Amunhotep III, Lord of All the World, sat on a chair beside his lion couch, naked but for a wisp of fine linen draped across his loins and a soft blue bag wig surmounted by a golden cobra. The gentle yellow light from the dozens of lamps in stands or on the low tables scattered about the chamber slid like costly oils over his broad shoulders, the loose swell of his belly, the thick paleness of his massive thighs. His face was unpainted. The once square, forceful jaw was now lost in folds of sagging flesh, the cheeks sunken and drawn, evidence of the lost teeth and gum disease that plagued him. His nose had flattened as he had aged, balancing the decay of his lower face, and only the high, tight forehead and the black eyes that still dominated even without kohl told of the handsome, florid youth he had been. One foot rested on a stool while a slave, cosmetic box open beside him and brush in hand, knelt to paint the royal sole with red henna. Tiye glanced about. The room smelt of stale sweat, heavy Syrian incense, and wilting flowers. Though a slave was moving quietly from one lamp to another, trimming their wicks, the flames gave off a gray miasma that stung her throat and left the room so dusky that Tiye could barely make out the giant figures of Bes, god of love, music, and the dance, that gyrated silently and clumsily around the walls. Now and then a flicker would illuminate an extended red tongue or a silver navel on the dwarf deity's swollen belly or would run rapidly