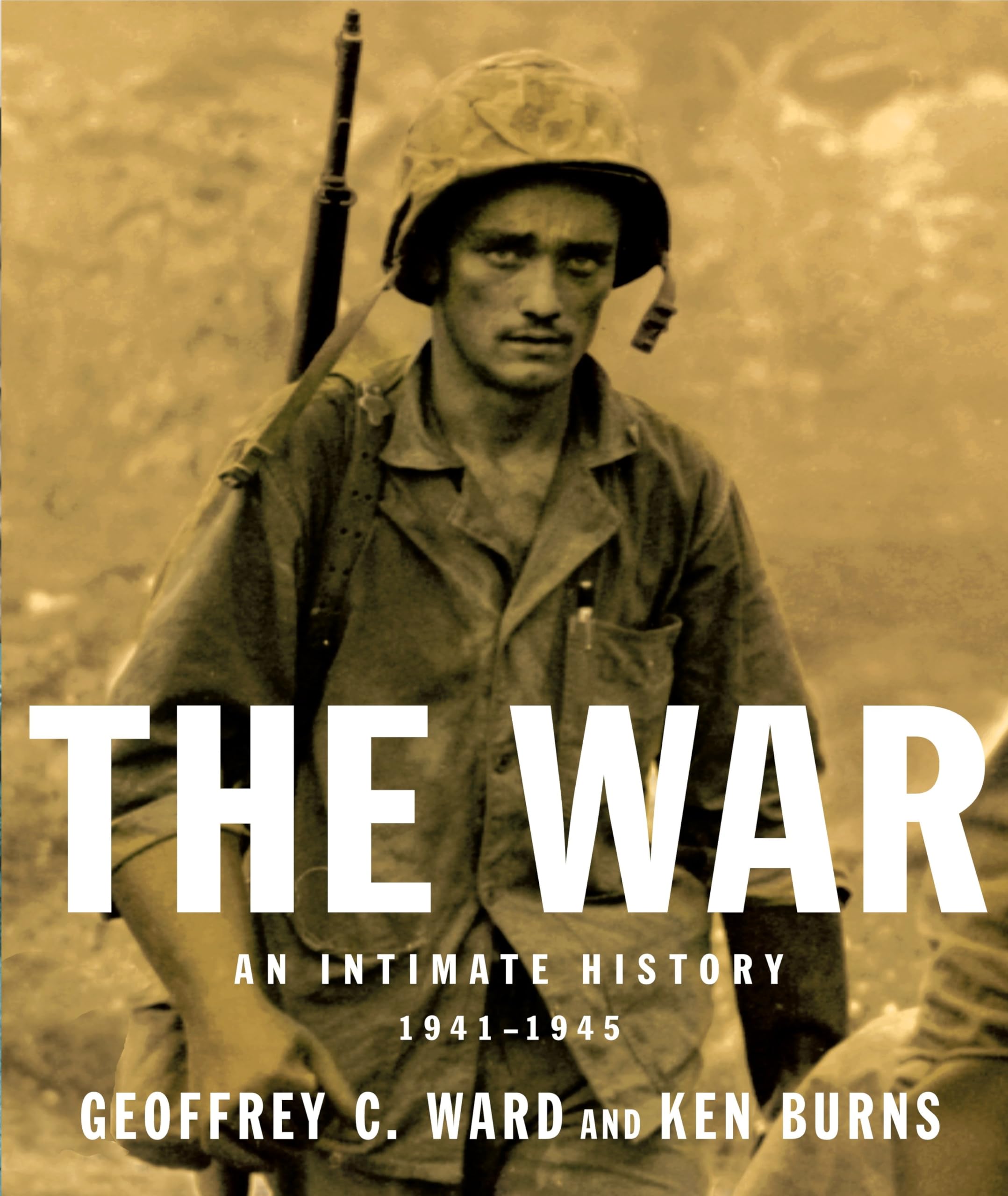

An intimate, profoundly affecting chronicle of the most devastating war in history, as told through the voices of ordinary men and women who experienced—and helped to win—it. • Includes maps and hundreds of photographs. Focusing on the citizens of four towns—Luverne, Minnesota; Sacramento, California; Waterbury, Connecticut; Mobile, Alabama—The War follows more than forty people from 1941 to 1945. Woven largely from their memories, the compelling, unflinching narrative unfolds month by bloody month, with the outcome always in doubt. All the iconic events are here, from Pearl Harbor to the liberation of the concentration camps—but we also move among prisoners of war and Japanese American internees, defense workers and schoolchildren, and families who struggled simply to stay together while their men were shipped off to Europe, the Pacific, and North Africa. “Ken Burns has done it again. He has given us an intimate, memorable, and provocative portrait of America in World War II—the valor and victory, sacrifice and shame of ordinary Americans, north, south, east, and west. This is a treasure.” —Tom Brokaw “Heartrending...Unique not only among previous volumes that have accompanied Burns’s documentaries but among just about any book on World War II.... It should be read by everyone in the family, from the high-schoolers to the Baby Boomers.” —Newark Star-Ledger GEOFFREY C. WARD wrote the script for the film series The War and is the winner of five Emmys and two Writers Guild of America awards for his work for public television. He is also a historian and biographer and the author of fourteen books, including most recently Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson. He won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1989 and the Francis Parkman Prize in 1990. He lives in New York City. KEN BURNS, producer and director of the film series The War, founded his own documentary company, Florentine Films, in 1976. His films include Jazz, Baseball, and The Civil War, which was the highest-rated series in the history of American public television. His work has won numerous prizes, including the Emmy and Peabody Awards, and received two Academy Award nominations. He lives in Walpole, New Hampshire. Chapter One December 1941-December 1942 A Necessary War I don't think there is such a thing as a good war. There are sometimes necessary wars. And I think one might say, "just" wars. I never questioned the necessity of that war. And I still do not question it. It was something that had to be done. —Samuel Hynes Sunday morning, December 7, 1941, began as most days do in Honolulu: warm and sunny with blue skies punctuated here and there by high wisps of cloud. At a few minutes after eight o'clock, the Hyotara Inouye family was at home on Coyne Street, getting ready for church. The sugary whine of Hawaiian music drifted through the house. The oldest of the four Inouye children, seventeen-year-old Daniel, a senior at William McKinley High and a Red Cross volunteer, was listening to station KGMB as he dressed. There were other sounds, too, muffled far-off sounds to which no one paid much attention at first because they had grown so familiar over the past few months. The drone of airplanes and the rumble of distant explosions had been commonplace since spring of the previous year, when the U.S. Pacific Fleet had shifted from the California coast to Pearl Harbor, some seven miles northwest of the Inouye home. Air-raid drills were frequent occurrences; so was practice firing of the big coastal defense batteries near Waikiki Beach. But this was different. Daniel was just buttoning his shirt, he remembered, when the voice of disk jockey Webley Edwards broke into the music. "All army, navy, and marine personnel to report to duty," it said. At almost the same moment, Daniel's father shouted for him to come outside. Something strange was going on. Daniel hurried out into the sunshine and stood with his father by the side of the house, peering toward Pearl Harbor. They were too far away to see the fleet itself, and hills further obscured their view, but the sky above the harbor was filled with puffs of smoke. During drills the blank antiaircraft bursts had always been white. These were jet-black. Then, as the Inouyes watched in disbelief, the crrrump of distant explosions grew louder and more frequent and so much oily black smoke began billowing up into the sky that the mountains all but vanished and the horizon itself seemed about to disappear. At that point, Daniel remembered, "all of a sudden, three aircraft flew right overhead. They were pearl gray with red dots on the wing—Japanese. I knew what was happening. And I thought my world had just come to an end." He had no time for further reflection. The telephone rang. He was needed at the nearest aid station right away. A stray American antiaircraft shell had fallen into a crowded neighborhood. There were ci