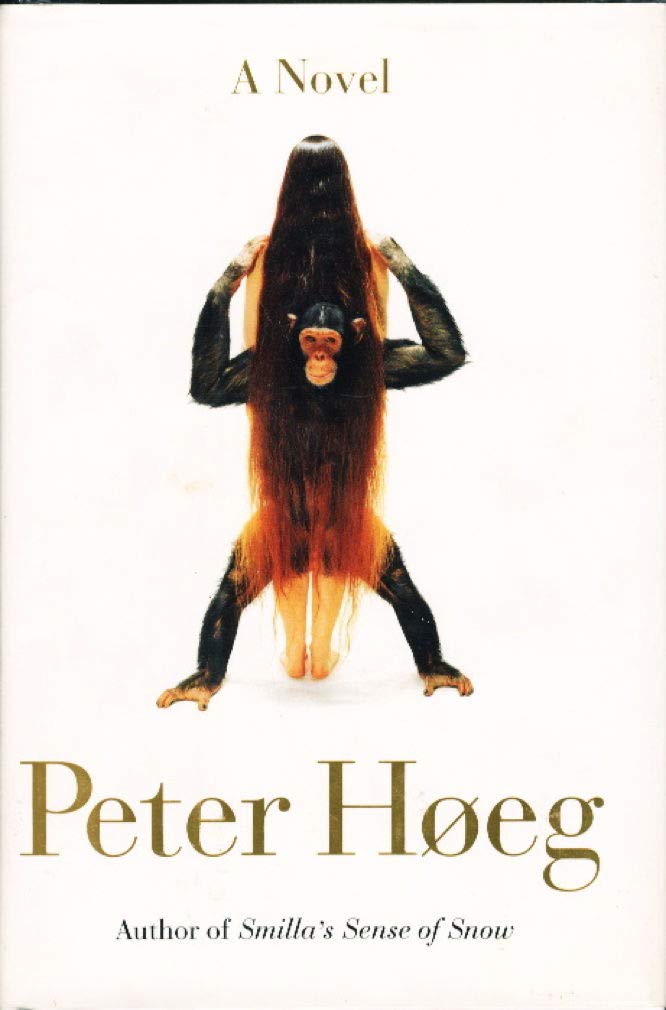

An emotional and erotic love affair develops between Madelene, the beautiful, disillusioned wife of Adam Burden, and Erasmus, the intelligent ape brought to the Burdens' London home after escaping animal smugglers. 100,000 first printing. Peter Høeg, author of the international bestseller Smilla's Sense of Snow, has written a fable that explores our human status as inhabitants of paradise lost, and the trade-off between civilization and freedom. The story begins with a captured ape, dubbed Erasmus, a specimen of an apparently new species with a cognitive ability that seems to rival human capacities. Erasmus is rescued from scientific study and experimentation by Madelene, whose husband, Adam, is the zoo director. Escaping to an Eden-like nature reserve, Madelene finds an empathy with Erasmus that develops into a wild sexual liberation. When the pair emerge from Eden to try to stop Adam continuing researches on others of Erasmus' kind, paradise dissolves, and civilization wins out. Read an interview with Peter Høeg. From Smilla's Sense of Snow to Borderliners to A History of Danish Dreams, Danish novelist HYeg has maintained a sharp sense of social critique that, refreshingly, is not wittily dismisive but earnest without being heavy-handed. And what better way to show up human heartlessness and pretension, particularly of the ruling classes, than in our treatment of animals? In this swift-paced, lacerating new work, an ape brought illegally to England ends up at the home of Madelene, a Danish woman married to Adam Burden, director of the Institute of Animal Behavioral Research. Madelene is young, fresh, and deeply alcoholic, but through the glassy haze that HYeg describes so effectively?from the inside out, not simply for dramatic effect but almost as an aesthetic experience, like being in a crystal cage?she can tell the ape is in danger. Madelene sets out to rescue the ape from her coldly calculating husband and his even more frigid sister and, in the process, rescues herself. That is the only predictable aspect of this thought-provoking work, which is too fresh in its writing and its perceptions to fall into the sentimentality one might expect. An air of freedom surrounds Madelene's eventual abduction by the ape, and though their sexual involvment may seem over the top to some readers, you can't help but be carried along by HYeg's convictions. Don't think King Kong; this is much subtler. Highly recommended. -?Barbara Hoffert, "Library Journal" Copyright 1996 Reed Business Information, Inc. No imaginative writer working today is any more daring than Danish novelist Peter Hoeg, any more willing to shock readers with something that is genuinely new. He did it with Smilla's Sense of Snow (1993), which asked us to reimagine what a thriller could be, and he does it again with this utterly original mix of fantasy, fable, myth, and love story. Stimulating the same archetypal nerves that respond to such sentimental save-the-animals sagas as Born Free , Hoeg forces us to confront the unavoidable realization that the animals, humans included, cannot be saved, that civilization itself is the inevitable enemy of freedom. These are not new ideas, of course--ask Huck Finn about civilization--but Hoeg faces them with a brutal honesty that is as rare as it is moving. The story seems too locked in the world of children's fantasy to support such subversive ideology, but that is only one of the conventional assumptions that must be shed as we read this most unconventional novel. When Madelene, the stifled, alcoholic wife of a London zoo director, decides to help free an ape that is soon to become the prize exhibit in her husband's zoo, she hardly expects to wind up fleeing London on this extraordinary ape's back, soaring with all the magic of E. T. across the city's rooftops and treetops and out of the grasp of all the lab-coated, needle-poking, deadly seekers of knowledge and understanding. Least of all does Madelene expect to fall in love with the ape and to share with him an erotic ecstasy far beyond the bounds of that diminished, cerebral thing we call human sexuality. Remarkably, we meet each outlandish turn in this story not with incredulity or disgust but with excitement and a sense of revelation. As an anti-utopian fable in which civilization, the enemy, triumphs over disorder, the novel threatens to leave some readers disoriented, their emotional compasses twirling. Yet others will find its vision on target, its expression of unfettered love both profoundly beautiful and refreshingly sexy, and its melancholy conclusion that "there is no such thing as a private Paradise" ineffably sad. Hoeg isn't the first to remind us that today's Huck Finns have no way to escape civilization, but he shows us exactly what we've lost more vividly than we've been shown in a long, long time. Bill Ott Heg's fourth novel (his third, the international success Smilla's Sense of Snow, 1993, having been the first published here) is an e