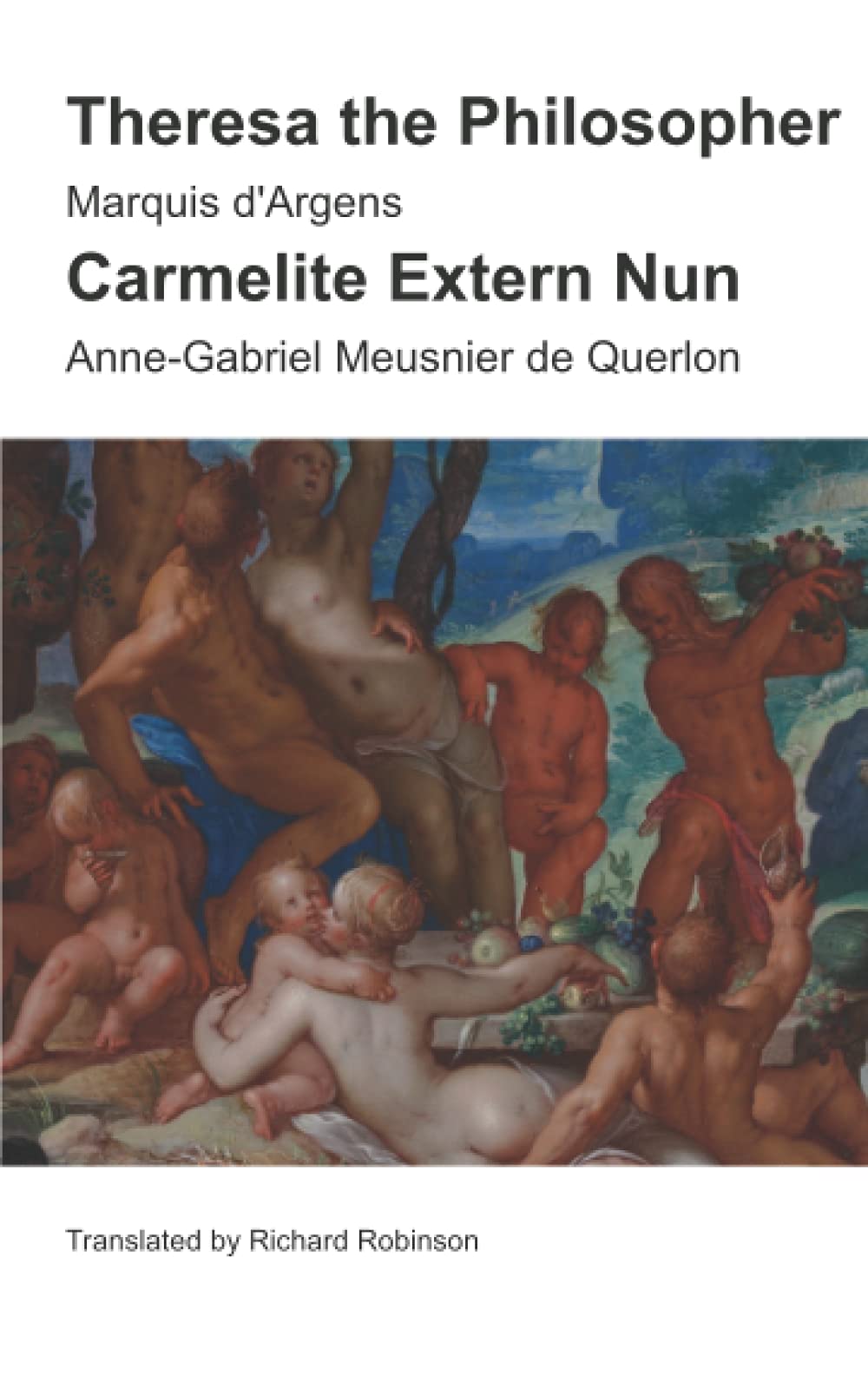

Theresa the Philosopher & The Carmelite Extern Nun: Two Libertine Novels from 18th-Century France

$15.95

by Marquis D'Argens

Shop Now

Theresa the Philosopher , by the marquis dʼArgens (purportedly), was published in 1748, over 270 years ago – before the modern era, before the Napoleonic phenomenon, before the Directorate, before the French Revolution. It is a happy tale with a happy ending, with not a little bit of hanky-panky slapped in between. Compared to Samuel Richardson’s Pamela , published in 1740, which was the first modern (albeit English) novel, whose characters are more than two-dimensional and whose story depends more on what happens inside the mind of the characters than, say, where a boat might go (like Robinson Crusoe for example) – Theresa the Philosopher is scandalous. Compared to the marquis de Sade’s Justine , which was published in 1791, it may seem tame. According to the marquis de Sade, Theresa the Philosopher “achieved happy results from the combining of lust and impiety... [it] gave us an idea of what an immoral book could be.” The Carmelite Extern Nun , written by Anne-Gabriel Meusnier de Querlon, and published one year earlier, in 1747, is another whopper. It is the “Amorous True Story [of Saint Nitouche], the Carmelite Extern Nun, Written by Herself, and Addressed to her Mother Superior.” It is anticlericalism, antiestablishmentarianism, and eroticism – the three main pillars or themes, sometimes even agendas, of the 18th century libertine novel – all in one short, but fast-paced, scandalous sack.