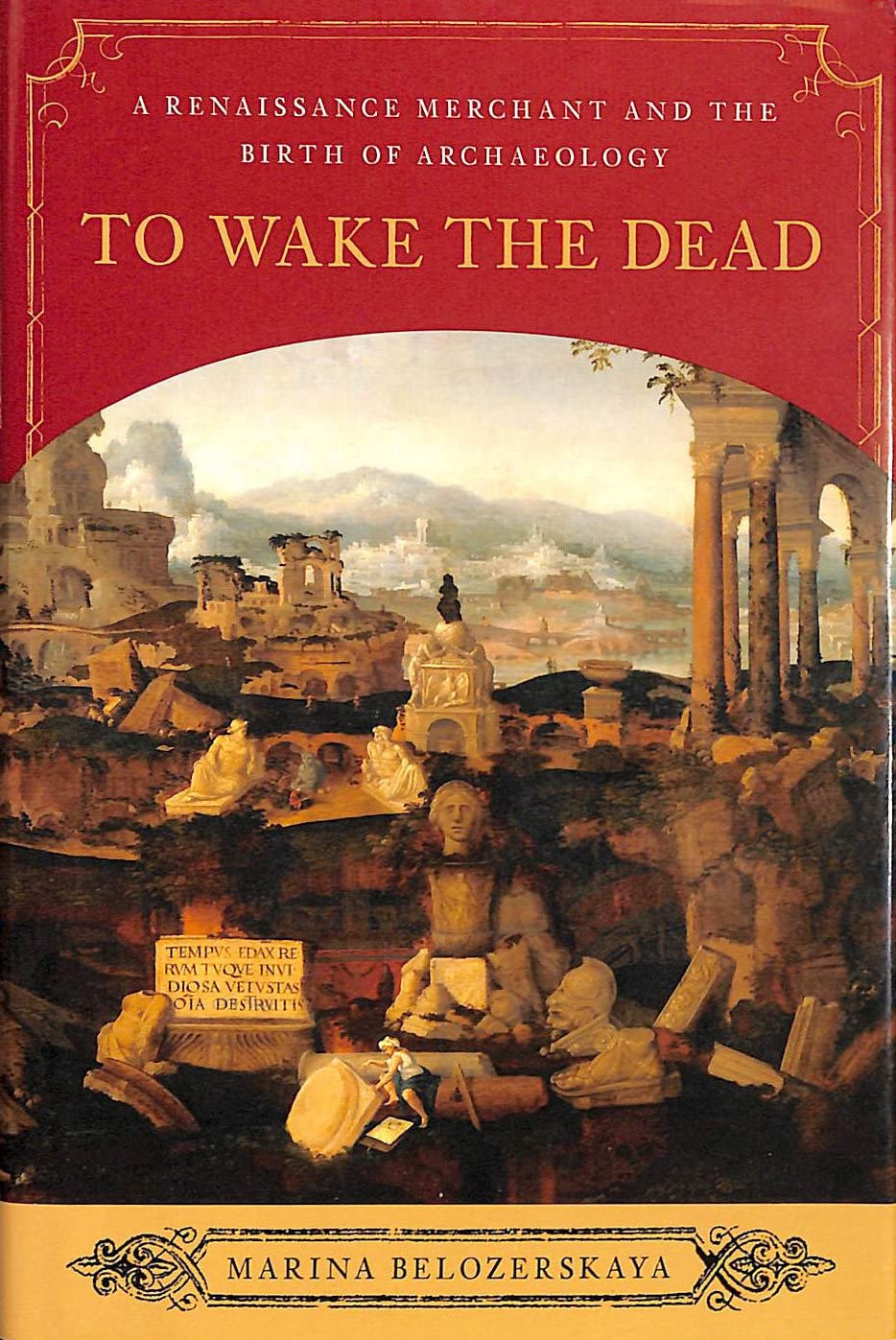

To Wake the Dead: A Renaissance Merchant and the Birth of Archaeology

$26.00

by Marina Belozerskaya

Shop Now

How Cyriacus of Ancona―merchant, spy, and amateur classicist―traveled the world, fighting to save ancient monuments for posterity. At the beginning of the fifteenth century, a young Italian bookkeeper fell under the spell of the classical past. Despite his limited education, the Greeks and Romans seemed to speak directly to him―not from books but from the physical ruins and inscriptions that lay neglected around the shores of the Mediterranean.As an international merchant, Cyriacus of Ancona was accustomed to the perils of travel in foreign lands―unlike his more scholarly peers with their handsome libraries and wealthy patrons, who benefited greatly from the discoveries communicated in his widely distributed letters and drawings. Having seen firsthand the destruction of the world’s cultural heritage, Cyriacus resolved to preserve it for future generations. To do so he would spy on the Ottomans, court popes and emperors, and even organize a crusade.25 illustrations Marina Belozerskaya is the author of The Medici Giraffe: And Other Tales of Exotic Animals and Power , The Arts of Tuscany from the Etruscans to Ferragamo , and Luxury Arts of the Renaissance . She lives with her husband in Los Angeles. From The Washington Post's Book World/washingtonpost.com Reviewed by Matthew Shaer Most medieval Europeans cared not a whit for the vestiges of antiquity. Back then, a stone arch was just a stone arch, regardless of its provenance, and in cities such as Siena and Rome thousands of valuable statues were left to fade and fracture under the sun. The policy of indifference extended even to the most majestic old buildings, many of which were incorporated into new churches and fortresses. After all, as Marina Belozerskaya writes in her fine history "To Wake the Dead," it was easier to add on to an existing structure than to build one from the ground up. Belozerskaya's hero is Cyriacus of Ancona, an Italian merchant, spy, writer and diplomat who, in the 15th century, began to travel through the Mediterranean and the Middle East in search of "distant civilizations and the ghosts of their denizens." His successes were many: He catalogued sites in Damascus, Eretria, Thessalonica and Beirut, and he worked tirelessly with local leaders to help preserve historical treasures that might have otherwise been destroyed. He pushed for more thorough examinations of primary sources and left behind sheaves of studies from far-flung corners of the globe. Less happily, Cyriacus also lobbied for a crusade against the Turks, which he hoped would help wrest important pieces of antiquity from foreign hands. But in his eagerness he overlooked the explosive political realities of the age, and many relics were lost in the resulting war. To Belozerskaya, Cyriacus was a tragic figure: a founder of modern archaeology and a man whose passion for the past "was both his strength and weakness." Copyright 2009, The Washington Post. All Rights Reserved.