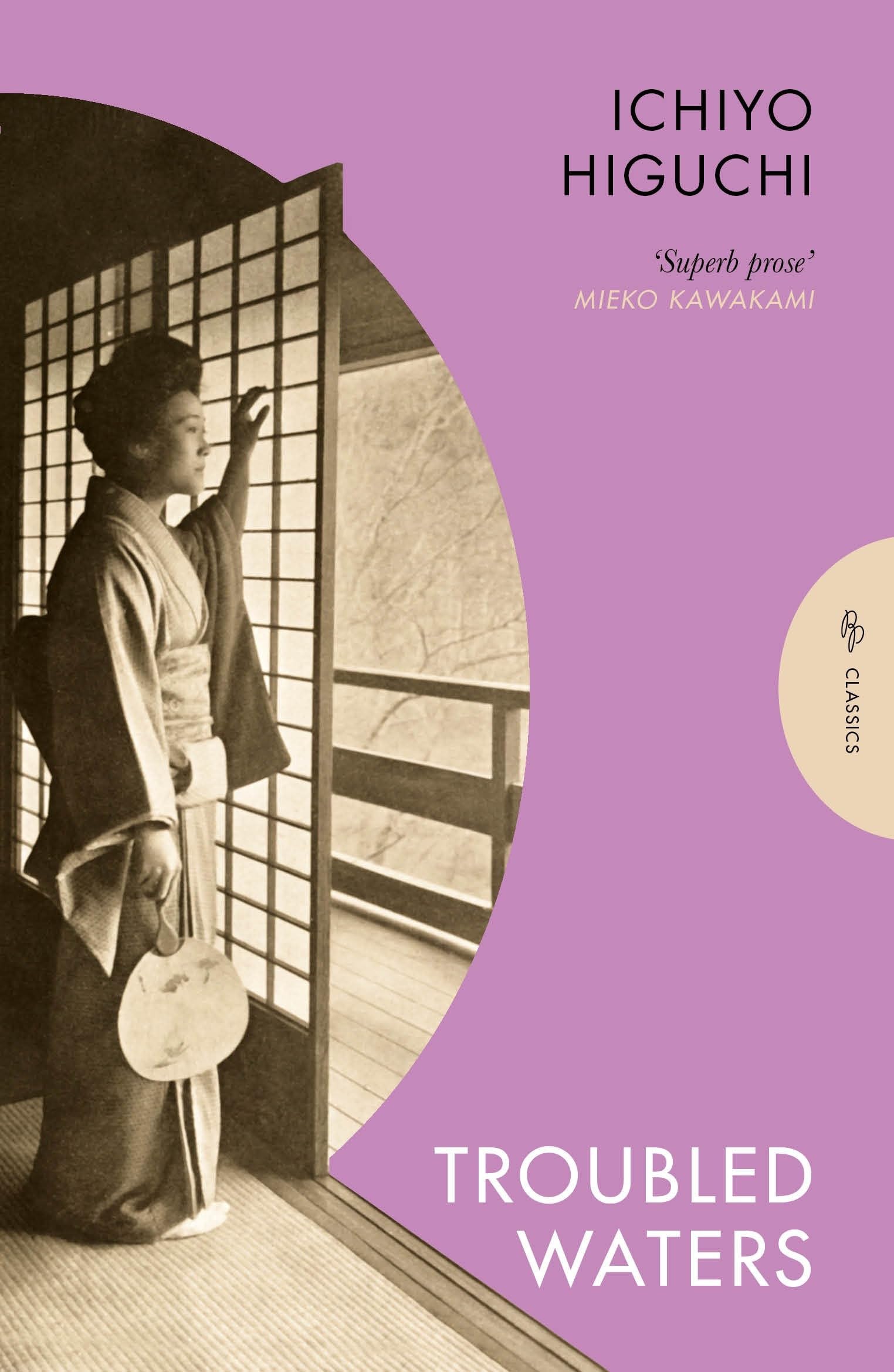

A new translation of 5 remarkable stories from Japan’s first professional woman writer, chronicling the lives of the turn-of-the-century working class This collection of short stories, several never before translated, brings the work of Ichiyo Higuchi to an English readership for the first time. In her brief life, cut short by tuberculosis at the age of 24, she became the first woman in Japan to make a living as a writer. A major figure of turn-of-the-century Meiji-era literature, she left behind her a collection of short stories, poems and diaries that turned creative attention to the lives of Tokyo’s poor and broke a path for women and realist fiction writers alike. In the title story, ‘Troubled Waters’, courtesan Oriki dismisses a lover who can no longer afford to pay for her favors – but when his obsession continues the consequences for both, and for his wife and child, will turn tragic. ‘Growing Pains’, one of the single most famous short stories in Japanese literature, depicts the coming of age of a group of children in Tokyo’s red-light district. Lively Midori, serious Nobu and hardworking Shota find childhood and its freedoms coming to a close over the course of a season, bookended by summer and winter festivals whose events prove decisive for each of their lives. These and 3 other stories are rendered in a fresh translation by Bryan Karetnyk, giving English readers access to Higuchi’s sensitive moral awareness, earthy street humor, and elegiac rendering of life’s inevitable compromises. "Subtle, precise and deft, the five stories in Troubled Waters are full of longing, written with exceptional control, and—in this sensitive and intelligent translation by Bryan Karetnyk—brimming with the richness and intensity of inner lives." —Lucy Caldwell, author of These Days Ichiyo Higuchi (1872-1896) came from a middle-class Tokyo family which slipped into poverty over the course of her childhood. After the deaths of her father and brother, she and her mother and sisters were forced to take in laundry and sewing to survive, and she began publishing her fiction and poetry in an attempt to shore up the family finances. She earned quick recognition for her combination of classical style with attentive observation of working-class street life, but her career was short-lived – she died of tuberculosis at the age of 24, only four years after her first publication. Still much read in Japan, her portrait graces the 5,000-yen note. Bryan Karetnyk is a British writer rand translator from the Russian and Japanese. His work for Pushkin Press includes books by Gaito Gazdanov, Irina Odoevtseva, Ryunosuke Akutagawa and Jun’Ichiro Tanizaki. As snowflakes flutter gently in the air like the dancing wings of butterflies, dusting the earth as far as the eye can see in a powder of argent, their six-petalled crystals land on trees stripped bare by winter, a vista of spring blossoms to come. How I envy those whom such a scene moves to compose verse and song enumerating the snow’s many beauties alongside those of the moon and flowers. Alas! for me the endlessly falling snow conjures but sorrow- ful and bitter memories of a past that cannot be shaken off. Myriad regrets I have, and each one of them in vain. What a waste—what impiety!—to have forsaken the land of my ancestors, to have disobeyed even the aunt who raised me with such tenderness. Now I have besmirched the very name my parents bestowed on me. They called me Tama—their Pearl—believing the word impervious to tarnish. Never would they have dreamt that my wretched existence would end up as worthless as a broken tile. Yet into a mountain stream I fell, and, borne by the current, I found myself in troubled waters. My youth was my downfall, my sin love, and the go-between a snowy day. I was born in the mountains, in a hamlet where the grass grows deep. Ours was an eminent family, whose name, Usui, was known throughout the region. An only child, I was the last in the family line. Both my parents departed this world, alas, before their time, and so it was my aunt—who had mar- ried into another family, only then to lose her husband—who returned home to take charge of me. And yet, from the time that I was almost three, she devoted herself to my upbringing as though I were her own. Even the gentle, tender love of a parent, I dare say, could not surpass hers. When I reached my seventh year, she arranged for a master of calligraphy to tutor me, and herself spared no efforts instructing me in music. But even so, no gatekeeper can check the passage of years… One day, the folds in my maiden’s kimono were lowered, and I began to pluck my eyebrows. What a joy it was to wrap a woman’s broad obi about my waist. And yet, to think back on it now—what folly! I may have grown as tall as my years decreed, but there could be no comparing my cultivation to that of the young ladies of the capital. In that respect, I was a mere child, quite unaware of the differences between men and wome