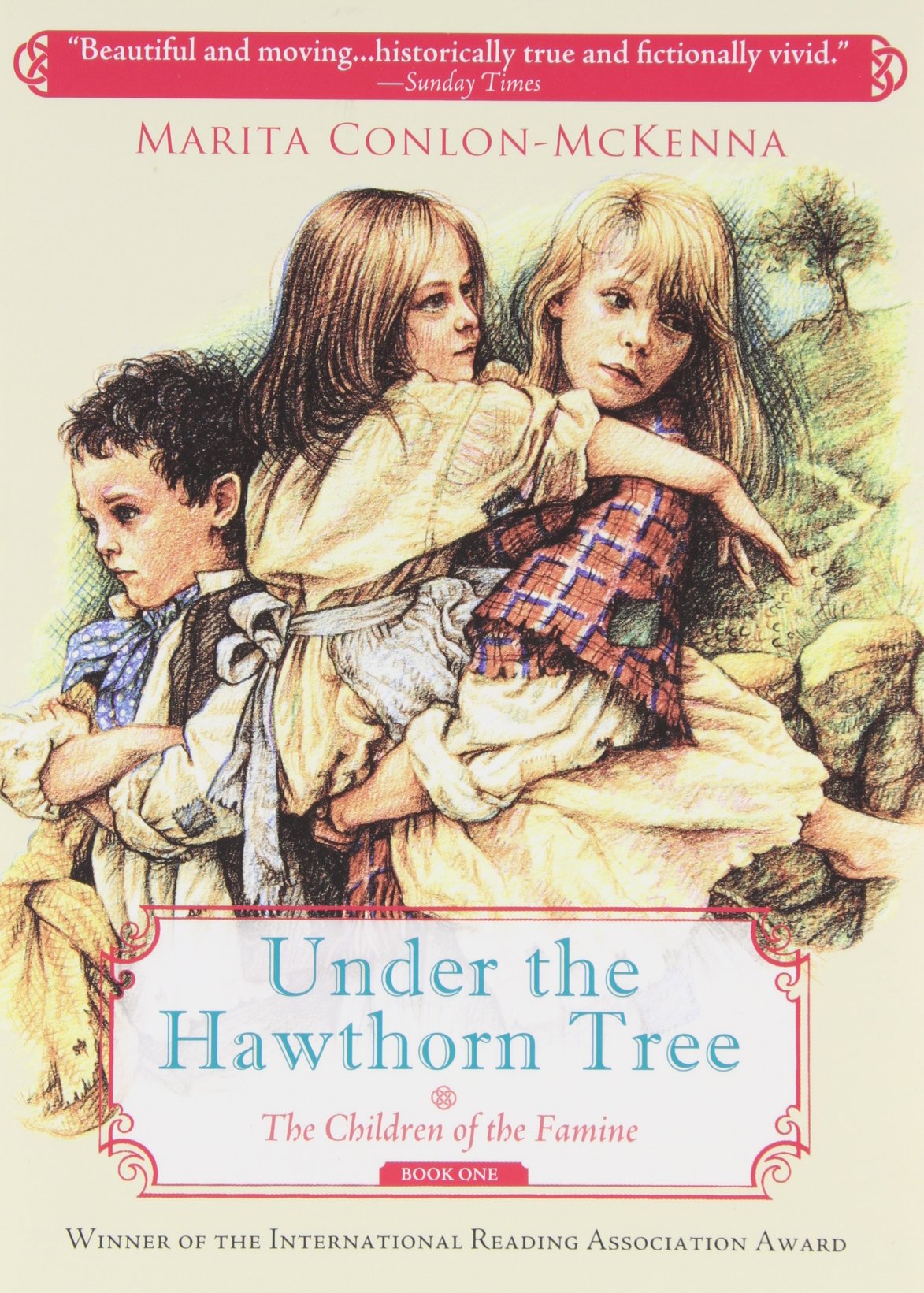

One of the greatest historical fiction adventures in children's literature. Marita Conlon-McKenna's Children of the Famine series brings to life as never before the Great Famine of 1840s Ireland and the immigrations that followed. Winner of many awards and accolades, these are all-time classics in historical fiction for children. Join siblings Eily, Michael, and Peggy on their incredible journey as they overcome tragedy, famine, and poverty to make their way in a dangerous new world. "Beautiful and moving…historically true and fictionally vivid."― Sunday Times "Not a word, spoken or unspoken, nor an emotion, is wasted. Pace and style keep the pages turning, and you are filled with a sense of wanting more at the end. Highly recommended."― Books Ireland "Brings to a satisfying conclusion one of the undoubted achievements of contemporary Irish children's literature."― Children's Books in Ireland "Three novels which, in my opinion, must be counted among the very highest achievements of contemporary children's writing - from Ireland or elsewhere."― Robert Dunbar Awards for Under the Hawthorn Tree 1991 International Reading Association Award - 1991 Reading Association of Ireland Award - 1993 ( Shortlisted for ) Österreichischer Kinder und Jugendbuchpreis - 1994 ( Shortlisted for ) Le Prix Litteraire du Roman pour Enfants Marita Conlon-McKenna is one of Ireland's most popular children's authors. She has written nine bestselling children's books. Under the Hawthorn Tree, her first novel, became an immediate bestseller and has been described as "the biggest success story in children's historical fiction." Marita lives in Dublin with her husband and four children. Excerpt from Chapter 1 Hunger The air felt cold and damp as Eily stirred in her bed and tried to pull a bit more of the blanket up to her shoulders. Her little sister Peggy moved against her. Peggy was snoring again. She always did when she had a cold. The fire was nearly out. The hot ash made a soft glow in the gloom of the cottage. Mother was crooning quietly to the baby. Brid get's eyes were closed and her soft face looked paler than ever as she lay wrapped in Mother's shawl, her little fist clinging to a piece of the long chestnut-colored hair. Bridget was ill they all knew it. Underneath the wrapped shawl her body was too thin, her skin white and either too hot or too cold to the touch. Mother held her all day and all night as if trying to will some of her strength into the little one so loved. Eily could feel tears at the back of her eyes. Sometimes she thought that maybe this was all a dream and soon she would wake up and laugh at it, but the hunger pain in her tummy and the sad ness in her heart were enough to know that it was real. She closed her eyes and remembered. It was hard to believe that it was only a little over a year ago, and they sitting in the old schoolroom, when Tim O'Kelly had run in to get his brother John and told them all to "Make a run home quick to help with lifting the spuds as a pestilence had fallen on the place and they were rotting in the ground." They all waited for the master to get his stick and shout at Tim: Away out of it, you fool, to disturb the learning, but were surprised when he shut his book and told them to make haste and "Mind, no dawdling," and "Away home to give a hand." They all ran so fast that their breath caught in their throats, half afraid of what they would find at home. Eily remembered. Father was sitting on the stone wall, his head in his hands. Mother was kneeling in the field, her hands and apron covered in mud as she pulled the potatoes from the ground, and all around the air heavy with a smell that smell, rot ting, horrible, up your nose, in your mouth. The smell of badness and disease. Across the valley the men cursed and the women prayed to God to save them. Field after field of potatoes had died and rotted in the ground. The crop, their food crop was gone. All the children stared eyes large and frightened, for even they knew that now the hunger would come. Eily snuggled up against Peggy's back and soon felt warmer. She was drowsy and finally drifted back to sleep. "Eily! Eily! Are you getting up?" whispered Peggy. The girls began to stretch and after a while they threw off the blankets. Eily went over to the fire and put a sod of turf on the embers. The basket was nearly empty. That was a job for Michael. Both girls went outside. The early morning sun was shining. The grass was damp with dew. They didn't delay as it was chilly in their shifts. Back in the cottage, Mother was still asleep and little Bridget dozed against her. "Is there something to eat?" "Oh, Michael, easy known you're up," jeered Eily. "Go on, Eily, look, have a look," he pleaded. "Away outside with you and wash that grime off your face and we'll see then." The sunlight peered in through the open cottage door. The place is dusty and dirty, thought Eily. The baby coughed and woke. Eily took her and sat in the firesid