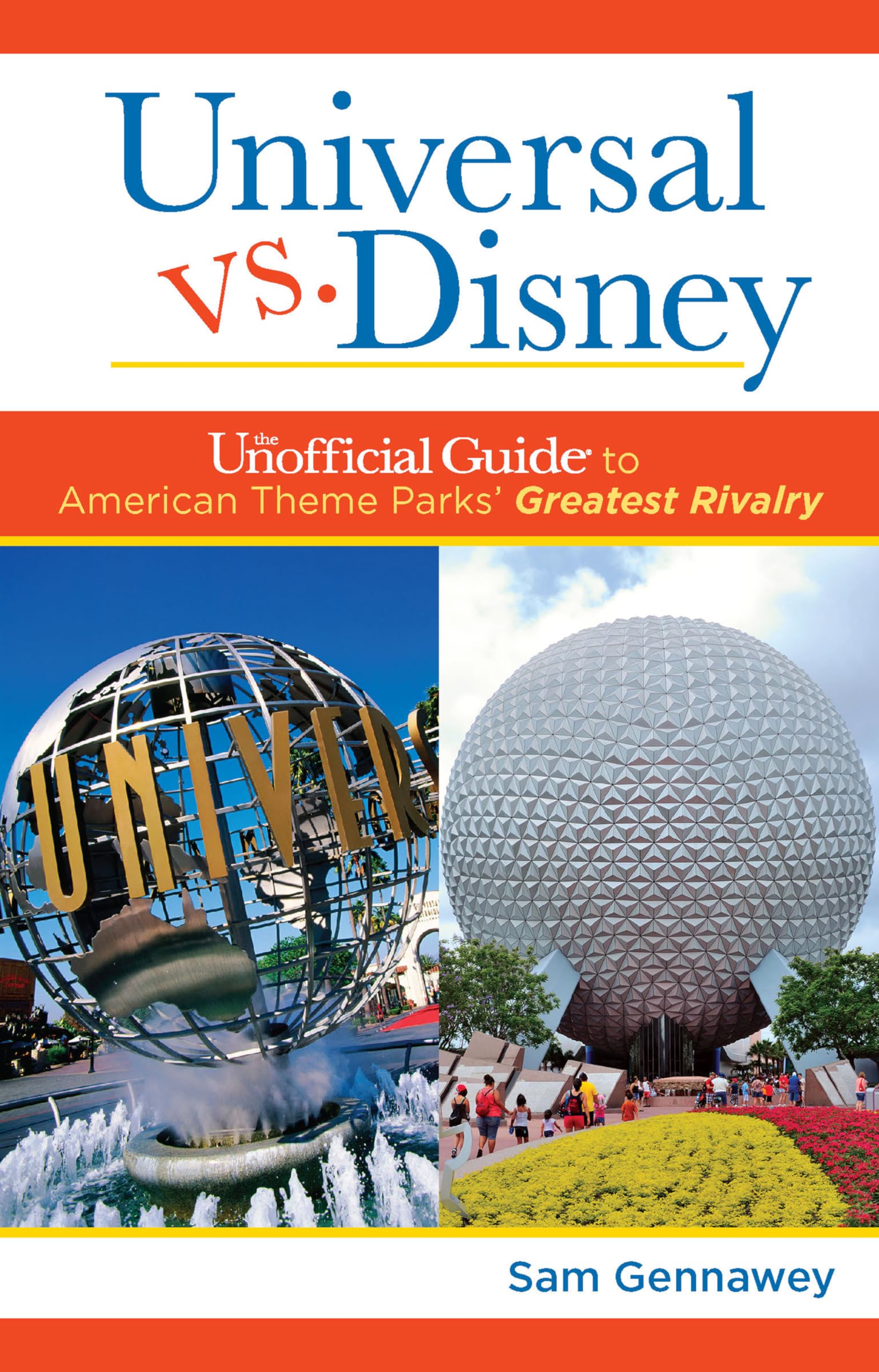

Universal versus Disney: The Unofficial Guide to American Theme Parks' Greatest Rivalry

$29.82

by Sam Gennawey

Shop Now

Universal Studios never really wanted to get into the theme park business. They wanted to be the anti-Disney. But when forced to do so, they did it in a big way. Despite the fits and starts of multiple owners, the parks have finally gained the momentum to mount a serious challenge to the Walt Disney Company. How did this happen? Who made it happen? What does this mean for the theme park industry? In Universal Versus Disney , his newest work to investigate the histories of America's favorite theme parks, seasoned Disney-author Sam Gennawey has thoroughly researched how Universal Studios shook up the multi-billion dollar theme park industry, one so long dominated by Walt Disney and his legacy. Introduction When an aspiring young director named Walt Disney came to Hollywood in 1923 to seek fame and fortune, one of his first stops was Universal City, home to Universal Studios. Universal Studios had been open to the public since it opened in 1915 and it's founder, Carl Laemmle, was the only studio chieftain who understood that the public was willing to pay to pull back the curtain and witness the creative process. And what the public wanted, Laemmle was happy to provide. What Walt Disney and thousands of others saw was a city dedicated to making movies. Disney must have been amazed at the sight of dozens of movies of every genre being filmed right in front of the public. Always curious, he was able to secure a day pass that allowed him to go beyond the public areas within his first year of arriving in Los Angeles. He wandered around the backlot for three days before the security guards threw him out. Undeterred, Disney returned to animation and would find another angle to get him back on the Universal lot. By the end of 1926, Universal was looking for its first cartoon to distribute and Laemmle asked Charles Mintz to find it. Mintz contacted Walt and Roy Disney to see if they had any ideas. The timing could not have been better since the brothers were already looking to replace the long running Alice's Wonderland cartoon series with something new. For Walt Disney, having his work distributed by a major studio would be a real coup. Walt and his chief animator Ub Iwerks drafted some sketches of a cute comedic rabbit wearing short pants and Mintz named him "Oswald the Lucky Rabbit." The series was a success and over the next two years Walt Disney produced twenty-six cartoon shorts. In 1928, he lost the character and much of his animation staff to Mintz and Universal during a contract dispute. Once again Disney was not deterred and would come back even stronger with Oswald's replacement, Mickey Mouse. When Walt Disney became a successful studio chief in the mid-1930s, he considered a tour of his studio on Hyperion Avenue but he felt the animation process would be too boring. He said, "You know, it's a shame people come to Hollywood and find there's nothing to see. Even people who come to the [Disney] Studio. What do they see? A bunch of guys bending over drawings. Wouldn't it be nice if people should come to Hollywood and see something? He toyed with the idea for years but nothing came of it. Instead, he decided to do something completely different and opened Disneyland in 1955. Disneyland put the guest onstage in immersive environments based on the popular movies and television genres of the day. The backstage would remain hidden. In the process, Walt Disney invented the theme park industry. A few years later, Universal Studios would be sold to entertainment powerhouse MCA. Lead by Lew Wasserman and Sidney Sheinberg, their team found an authentic way to satisfy the public's desire to go backstage that would not interfere with production. The result was an industrial tour that turned into a multi-million dollar business. Disneyland appealed to one audience and the Universal Studios Tour appealed to a different audience. Everybody was making money and everybody was happy. Then came Wasserman's growing ambitions, Michael Eisner and Frank Wells at Disney, and Universal's constant changes in corporate ownership. Circumstances would force Universal to move toward the Disney theme parks model of immersive fantasy environments with varying success. Even though Disney had the money and the creative heritage, Universal had one significant advantage. For many years at Disney, the theme parks were the tail that wagged the corporate dog. At Universal, the theme parks were a small flea on the back of the dog. This difference allowed a handful of ambitious people at Universal to gain a reputation as theme park innovators and they quietly reinvent an industry. Can the underdog become the top dog? CHAPTER ONE Carl Laemmle The driving force behind Universal Studios was Carl Laemmle, an immigrant from Bavaria, Germany. Like so many who came before, Laemmle moved to America in 1884 to find a better life. Like so many early Jewish immigrants, he did what he could with the education and resources available to him. He