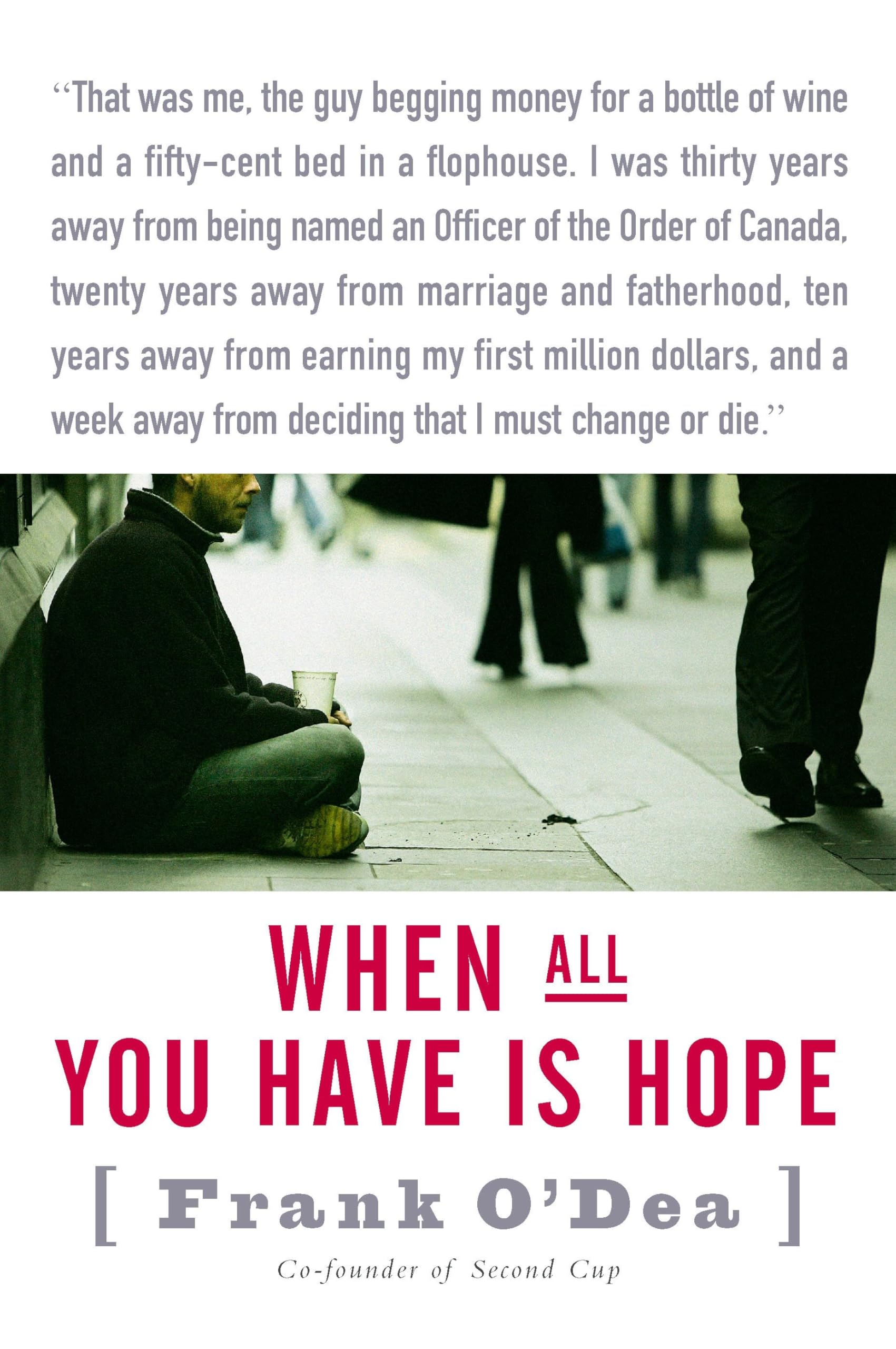

For entrepreneur Frank O’Dea, it was a long road from street life to the high life. Born in Montreal to an upper-middle class family, Frank’s life took a downturn as a young man when he was sexually assaulted by a priest. He began drinking at an early age and was soon destitute, living in degradation on the streets of Toronto. By way of a sympathetic employer, the Salvation Army, and Alcoholics Anonymous, O’Dea quit drinking and started a small business that developed into the Second Cup coffee chain. Over the years, his philanthropic activities extended to AIDS fundraising, child literacy in the Third World, and landmine removal. His message is simple: HOPE, VISION, ACTION. JOHN LAWRENCE REYNOLDS is the author of almost two dozen non-fiction books, including Bubbles, Bankers and Bailouts, the national bestseller The Naked Investor, and Free Rider: How a Bay Street Whiz Kid Stole and Spent $20 Million, winner of the National Business Book Award. He has also won two Arthur Ellis Awards for best mystery novel, a National Magazine Award, and an Author’s Award from the Foundation for the Advancement of Canadian Letters. He lives in Burlington, Ontario. [one] It Should Have Been Happy and Warm I stumble against the doorway. Must have drifted off there for a moment. Almost dropped the precious coins I'm holding. I open my hand to count the money. Twenty-five … thirty-five … I lose track and start over again. Fifty. Fifty-five. Sixty-five. Seventy-five cents. It is just after three o'clock. I am twenty-five cents short. The wind comes up, carrying the rain with it. Cold December rain that is certain to become snow by evening. Bad news. The lineup at the Salvation Army hostel will be longer than usual this evening. I need that twenty-five cents, that quarter of a dollar. I need it in a way I need air. I need it more than food. I need to use the bathroom, too. Cold air does that to you. But first I need to drink. Everything is needs. I am beyond wants. If I stand deeper in the doorway, the dirt-crusted windowed doorway of this empty store on Jarvis Street, I'll be out of the wind a little and won't shiver quite so violently. There won't be as much chilling breeze to pull at the T-shirt and plaid flannel work shirt that I have been wearing for … for weeks now. I tried to figure out how many weeks it's been just then. Lost count. That's not true. I did not lose count. I just don't want to know. Standing here deeper in the doorway, I'm not seen so easily by people going by, and if I'm not seen, I can't make eye contact with somebody who might give me a quarter. Like this fellow coming up the street. Wearing a coat with a fur collar. Smiling to himself as though somebody told him a joke, or he just decided what to buy his girlfriend for Christmas. He looks my age. Twenty-three, twenty-four years old. Nice shoes. Good haircut. What's twenty-five cents to him? I step out into the wind again, my hand extended. Damn. A police car just turned the corner at Shuter Street. Coming this way. I know the cop driving it. A mean SOB. Big guy. Thick black moustache. He'll stop at the curb, tell me to get the hell off the street. Maybe he'll get out of the car and slap the money from my hand, knock the coins into the gutter and stand there watching me shuffle away, down the street and around the corner. I couldn't take that. Not today. I withdraw my hand, step back into the doorway. I need to take the chance. “Any spare change?” I ask the man with the fur collar as he passes me. I startled him. He averts his eyes from mine, dropping them to my dirty plaid shirt, stained trousers, worn shoes, then away again. Maybe he smells me. I know I smell. I can't help it. You get sick, you don't wash often enough, you don't change your clothes, that's what happens. You smell. I want to explain this to him, but he keeps walking, not missing a stride. The police car passes. The officer hasn't noticed me either. Three hours to beg twenty-five cents here on the street. If I get seventy-five cents, a dollar for the wine and fifty cents for the flophouse, I won't have to go to the hostel tonight. I can share a room with Bruce and Doc and the other guys. The rain is getting heavier, the sky greyer, the air colder. Here comes a woman, older than me, with a sweet face. I'll smile at her, maybe remind her of her own son or a long-lost brother. Women are more generous than men. I force a smile to my face. It almost hurts. When did it start hurting to smile? That was me, the guy looking for a handout, begging money for a bottle of wine and a fifty-cent bed in a flophouse. The year was 1971. I was thirty years away from being named an Officer of the Order of Canada, twenty years away from marrying a beautiful and successful woman and fathering our two precious daughters, ten years away from earning my first million dollars, and a week away from deciding that I must either change or die. Let me paint you a pleasant picture, one you may envy. It's the 195