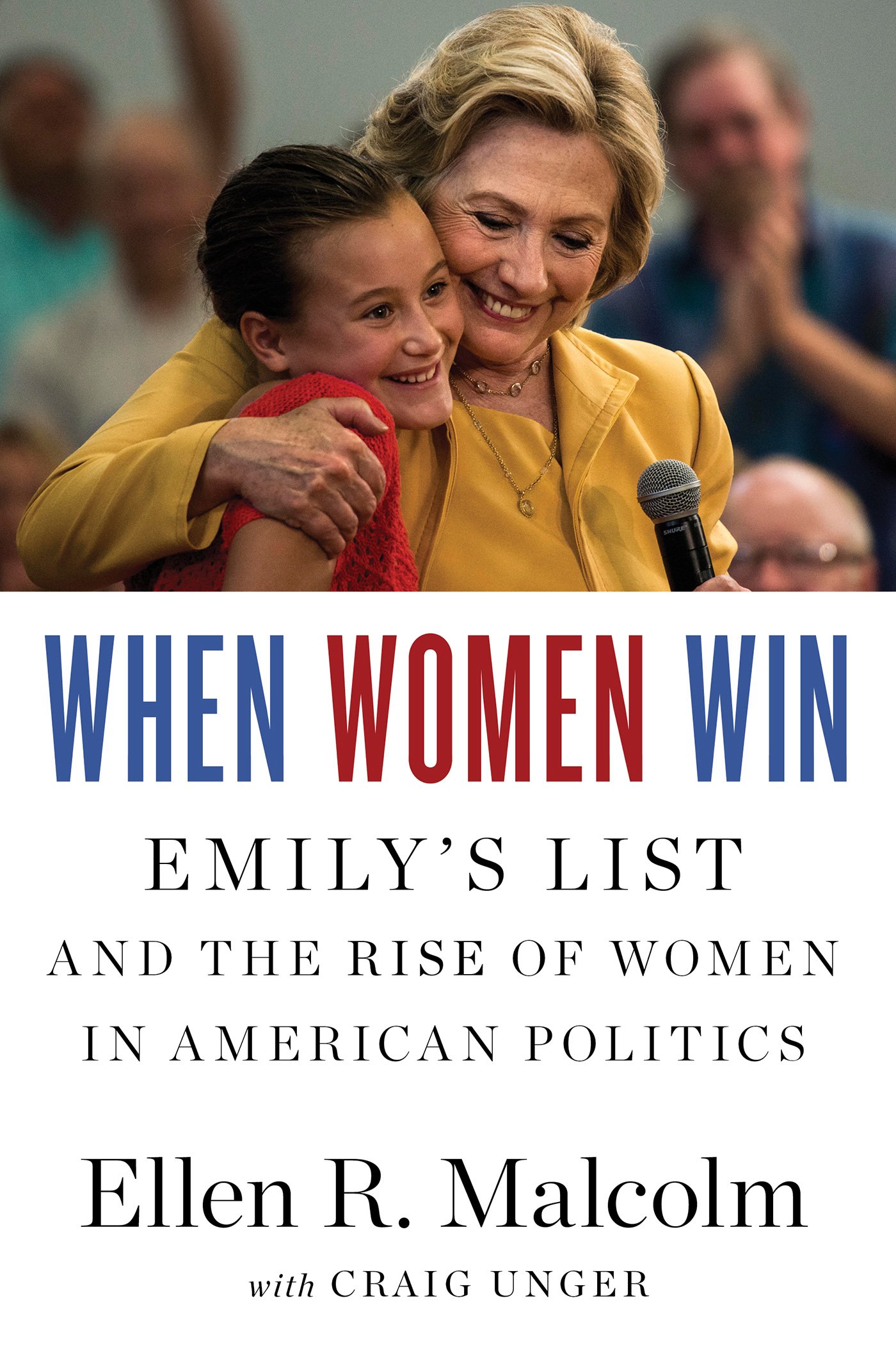

When Women Win: Emily's List and the Rise of Women in American Politics

$10.28

by Ellen R. Malcolm

Shop Now

The dramatic inside story of the rise of women in elected office over the past quarter-century, from the pioneering founder of three-million-member EMILY's List &; one of the most influential players in today&;s political landscape In 1985, aware of the near-total absence of women in Congress, Ellen R. Malcolm launched EMILY&;s List, a powerhouse political organization that seeks to ignite change by getting women elected to office. The rest is riveting history: Between 1986 &; when there were only 12 Democratic women in the House and none in the Senate &; and now, EMILY&;s List has helped elect 19 women Senators, 11 governors, and 110 Democratic women to the House. Incorporating exclusive interviews with Hillary Clinton, Nancy Pelosi, Tammy Baldwin, and others, When Women Win delivers stories of some of the toughest political contests of the past three decades, including the historic victory of Barbara Mikulski as the first Democratic woman elected to the Senate in her own right; the defeat of Todd Akin (&;legitimate rape&;) by Claire McCaskill; and Elizabeth Warren&;s dramatic win over incumbent Massachusetts senator Scott Brown. When Women Win includes Malcolm's own story &; the high drama of Anita Hill&;s sexual harassment testimony against Clarence Thomas and its explosive effects on women&;s engagement in electoral politics; the long nights spent watching the polls after months of dogged campaigning; the heartbreaking losses and unprecedented victories &; but it&;s also a page-turning political saga that may well lead up to the election of the first woman president of the United States. One: A Political Education I was an unlikely political activist. I grew up in the fifties and sixties in Montclair, New Jersey, an upper-middle-class suburb outside of New York. When I was eight months old, my father died of cancer and my mother, Barbara, became a twenty-four-year-old widow. Three years later, Mom remarried and left her job at IBM to stay home and raise her children. Her decision to quit work was never in doubt. That's what women did in the fifties'?if the family could afford it. When I entered Hollins College, an all-women's school in Roanoke, Virginia, in 1965, I was an eighteen-year-old preppie who was essentially apolitical. This was an era when men's schools and women's schools were more common than they are today, and it did not even occur to me to go to a coed school. I didn't even really know the difference between Democrats and Republicans, liberals and conservatives. I'd never heard of Vietnam, much less realized we were at war there, and I didn't even know that hundreds of thousands of Americans were protesting. But, in 1968, at the urging of a friend, I went to Philadelphia to work for Eugene McCarthy, the antiwar senator from Minnesota, during the Democratic presidential primary in Pennsylvania. I knocked on doors, handed out literature, and talked to people about the issues. McCarthy won 71 percent of the vote in Pennsylvania. I had just turned twenty-one and was now eager to vote in my first presidential election. It was 1968 in America. All across the country, the counterculture of the sixties was ascendant. A generation of antiwar protesters and long-haired hippies were replacing buttoned-down, crew-cut frat boys and sweater-and-pearls sorority sisters. Bob Dylan, the Beatles, and the Rolling Stones were on the airwaves. On the other side of the globe, the North Vietnamese launched the Tet Offensive against South Vietnam. U.S. campuses were in an uproar. On March 31, President Lyndon Johnson announced he would not seek reelection. Four days later, on April 4, 1968, I was crossing the Hollins campus when I heard that Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated. Hundreds of thousands of people rioted in New York, Washington, Chicago, Los Angeles, and dozens of other cities. On June 6, Bobby Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles. There were countless demonstrations all over the country. My political innocence was over. Both Montclair and my family were Republican to the core, but I headed off in a very different direction. Too much of what was happening in the sixties was close to home'literally. Just eleven miles from Montclair, Newark was the epicenter of the most violent racial upheavals of the time. The year before, six days of rioting, looting, and violence left 26 people dead, more than 700 injured, and 1,500 arrested'?not to mention millions of dollars in damages. In the aftermath of the King assassination, civil unrest spread to 125 cities. To affluent suburbanites like me, all this was shocking. By that summer, I was fully committed to fighting poverty and racism, as well as the war. I believed that job training could help the unemployed, so my mother found me a volunteer job at the Manpower development program in Newark. There I was, a nice, young, MG-driving white girl from Hollins, whose mother was urging her to join the Junior L