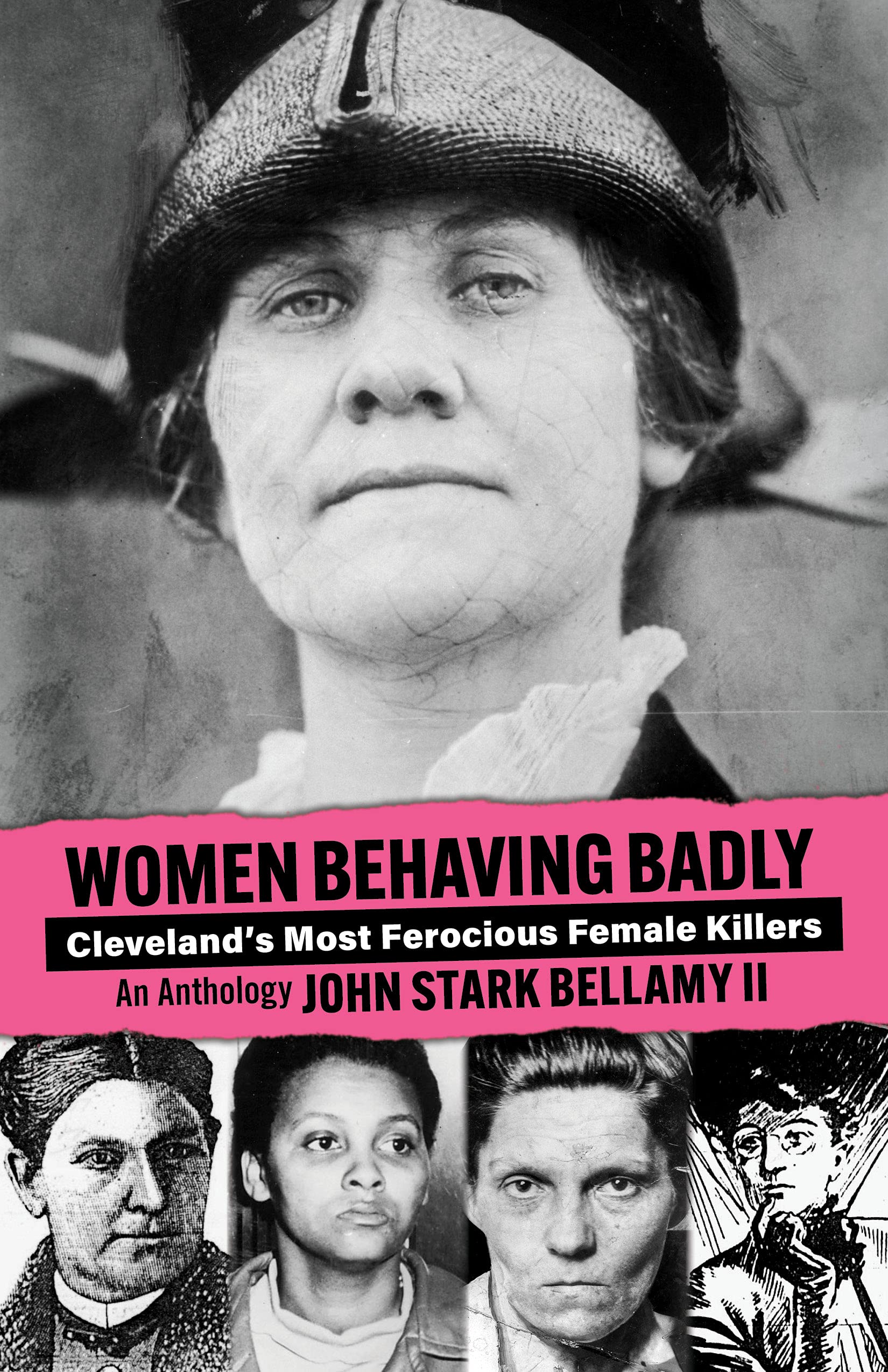

Women Behaving Badly: True Tales of Cleveland's Most Ferocious Female Killers: An Anthology

$34.98

by John Bellamy II

Shop Now

“Bellamy once again masterfully brings to life decades-old tales that won’t let you look away.” ― Cleveland Magazine Women who murder … why are they so much more fascinating than their male counterparts? For evidence, dip into any of the sixteen strange-but-true tales collected in this anthology by Cleveland’s leading historical crime writer. You’ll meet: Ill-fated Catherine Manz, the “Bad Cinderella” who poisoned her step-sister in revenge for years of mistreatment, then made her getaway wearing her victim’s most fetching outfit, a red dress and an enormous feathered hat … - Velma West, the big-city girl who scandalized rural Lake County in the 1920s with her “unnatural passions”―and ended her marriage-made-in-hell with a swift hammer’s blow to the skull of her dull husband, Eddie … - Eva Kaber, “Lakewood’s Lady Borgia,” who, along with her mother and daughter, conspired to dispose of an inconvenient husband with arsenic and knife-wielding hired killers … - Martha Wise, Medina’s not-so-merry widow, who poisoned a dozen relatives―including her husband, mother, and brother―because she enjoyed going to funerals … And a cast of other, equally fascinating women who behaved very, very badly. This is wickedly entertaining reading! From the Kaber case, which finds a grandmother, mother and granddaughter indicted for the same first-degree murder, to the ‘Bad Cinderella’ who poisons her abusive stepsister, Bellamy once again masterfully brings to life decades-old tales that won’t let you look away. -- Jim Vickers ― Cleveland Magazine Published On: 2005-11-05 A collection of true crime tales that can quickly disabuse anyone of the notion that women are really the ‘gentler’ sex. Any one of these would easily qualify for the supermarket tabloids. But they were taken from 150 years of murder and mysterious death cases pivoting around women in the greater Cleveland area. -- Laura Kennelly ― Morning Journal Published On: 2005-12-18 Nothing is open and shut in ‘Women Behaving Badly’. The latest look-back by true-crime maestro John Stark Bellamy recounts the life and crimes of Cleveland’s most gruesome killers . . . But more than that, it revisits sexual roles in transition, where change comes with a revolver, a knife, or cup of poison-and female intuition gone berserk. -- John Petkovic ― The Plain Dealer Published On: 2005-10-25 Fascinating, even in the preface . . . Great fun, in a gruesome sort of way . . . Straightforward and easy to read, and each case is short enough that when you finish one, you want to start on the next. -- Mary Ruehr ― Record Courier Published On: 2005-12-30 John Stark Bellamy II is the author of six books and two anthologies about Cleveland crime and disaster. The former history specialist for the Cuyahoga County Public Library, he comes by his taste for the sensational honestly, having grown up reading stories about Cleveland crime and disaster written by his grandfather, Paul, who was editor of the Plain Dealer, and his father, Peter, who wrote for the Cleveland News and the Plain Dealer. She Got Her Money’s Worth Eva Kaber, Lakewood’s Lady Borgia, 1919 “Happy families are all alike,” runs Tolstoy’s best one-liner. “Each unhappy family is unhappy in its own peculiar way.” And if you don’t believe it, consider the Kaber family. The time was July 15, 1919. The place was the Dan Kaber house, a posh, neo-Colonial showplace on fashionable Lake Avenue, several blocks west of the city of Cleveland. And the persons were the sharply disparate members of the Dan Kaber family―each desperately and uniquely unhappy. Dan Kaber, certainly, had the most objective reasons for being unhappy. Forty-six years old and formerly a healthy, active, well-to-do printer, Dan had within the past six months become a helpless, bedridden, pain-wracked invalid. Confined most of the time to his second-floor bedroom, Dan had lost the use of all his limbs, with the pitiful exception of the index and middle finger of his left hand. His decline had begun with an apparent influenza attack during the previous November, but despite lengthy hospital stays and futile surgery for suspected cancer of the stomach and appendicitis, Dan had steadily deteriorated. His doctors muttered vaguely about “rheumatism,” then “cancer” and “neuritis,” but it was plain they did not have a clue as to Dan Kaber’s malady. Dan Kaber was increasingly feeble, querulous, and seemingly fearful; he was apparently most fearful of his wife, Eva Kaber. Ever attentive, she insisted on personally feeding him―and quite often the soups, strawberries, and chocolates she proffered made him violently sick. Dan tried to complain to anyone who would listen that there seemed to be an awful lot of paprika in his food of late . . . but whenever he tried to tell his brother or father about his suspicions Eva would appear in the room. Eva Kaber wasn’t very happy in July 1919. Thirty-nine years old, she had struggled and schemed her way up from nothing to status as a