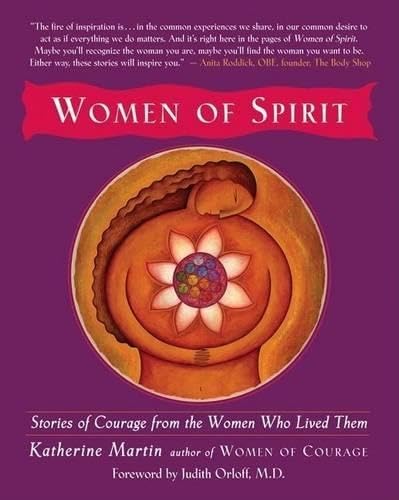

Women of Spirit: Stories of Courage from the Women Who Lived Them

$27.98

by Katherine Martin

Shop Now

Thirty-five women who succeeded in making a difference in the world relate their experiences in this inspiring collection. Katherine Martin introduces each first-person account with background information on the writer and the obstacles she faced. Lesser-known heroines include Debra Williams, who blew the whistle on medical malpractice in a midwestern prison; Sonya Bell, a blind teenager who became an award-winning runner; and Carrie Barefoot Dickerson, who stopped the construction of a nuclear power plant. Other stories, told in their own words, are about SARK, Judith Light, Julia Butterfly Hill, Joan Borysenko, Geraldine Ferraro, Iyanla Vanzant, and others. Women of Spirit Stories of Courage from the Women Who Lived Them By Katherine Martin New World Library Copyright © 2001 Katherine Martin All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-57731-149-2 Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS, FOREWORD by Judith Orloff, M.D., PRELUDE: Claiming Courage, Breathing Spirit, THE HAZEL WOLF STORY: A Courageous Life Lived, Inspired to Do the UNEXPECTED, Inspired to Face TRUTH, Inspired to Take a STAND, Inspired to Be YOU, Inspired to CHALLENGE, Inspired to PERSIST, DIRECTORY, MY STORY OF COURAGE, CHAPTER 1 Inspired to Do the UNEXPECTED Jon Borysenko "My children were suffering, my marriage was suffering. And, once again, my inside wasn't matching my outside.... Yet I couldn't get myself to leave. If I jumped ship at age forty-two, that was it for me. I'd never get back into an academic environment. And I'd have given up over twenty years of fussing and scraping and competing in order to do what I wanted.... If I left [Harvard], no one would ever listen to me again. I'd wither up in the suburbs, all alone and with nobody listening." Joan Borysenko, Ph.D., is one of the most prominent figures on the mind- body landscape, blending science, medicine, psychology, and spirituality in the service of healing. At one time a cancer researcher, she holds three postdoctoral fellowships from Harvard and cofounded the mind-body clinical program at Beth Israel/Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. It's hard for me to look though the threads of my life for a courageous moment. What on earth would that be? I was a pathologically shy child, practically crippled with fear. I had to rehearse speaking to people, going over and over a simple statement before I could make it. I never ate in front of people — that would have been much too embarrassing. And I've always feared doing the wrong thing, making the wrong choice, disappointing people. My life has been marked by things that I felt called to do, even though I was in some terrible state of fear. So mine is a wimpy story. To this day, I am painfully introverted, a rather odd thing for a person who travels the world two hundred days a year lecturing to thousands of people, looking for ways to build bridges and to inspire people to reach deep inside themselves for what is meaningful and kind and good in their lives. I'm a much better candidate for what I did in the earlier part of my career, which was being locked up in a laboratory with my microscope. I started on the path to that microscope when I was ten. In the fifth grade, I had a terrifying nightmare in which my family and I were in a jungle with headhunters chasing us and booby traps, snakes, and scorpions all around. When I awoke, I was literally in a psychotic state; I couldn't tell the dream from real life. I was absolutely sure that headhunters were chasing my family and would kill us all. I shook out my shoes, thinking scorpions were in them. Within days, I developed a second mental illness as a way of trying to cope with the first: obsessive-compulsive disorder. Excessive hand washing was just the beginning. During the next few months, I developed a dozen different ritual behaviors, such as reading upside down, backwards, and three times in a row. If I were interrupted in any of my rituals, I had to start over, because the rituals kept my family safe from horrors that only I could see, horrors that existed behind a thin veil in the unmanifest world. This was pretty potent stuff. I can't even begin to access the terror that I lived with during that time. My parents were so distressed that they would cry themselves to sleep at night. I could hear them and began trying to hide my behavior, because now I needed to protect them not only from the headhunters, snakes, and scorpions but also from the pain of not being able to help me. In spite of my efforts, I'd often get sent home from school — like the time I hallucinated that headhunters were running down the hall, throwing poison darts at me, which, through the extraordinary power of the mind, actually produced red marks on my arms. Believe me, when you go to the school nurse with red marks on your arms and say, "I've been hit by poison darts," they send you home fast! My parents took me to a psychiatrist who ran tests, but he didn't really know how to treat me.