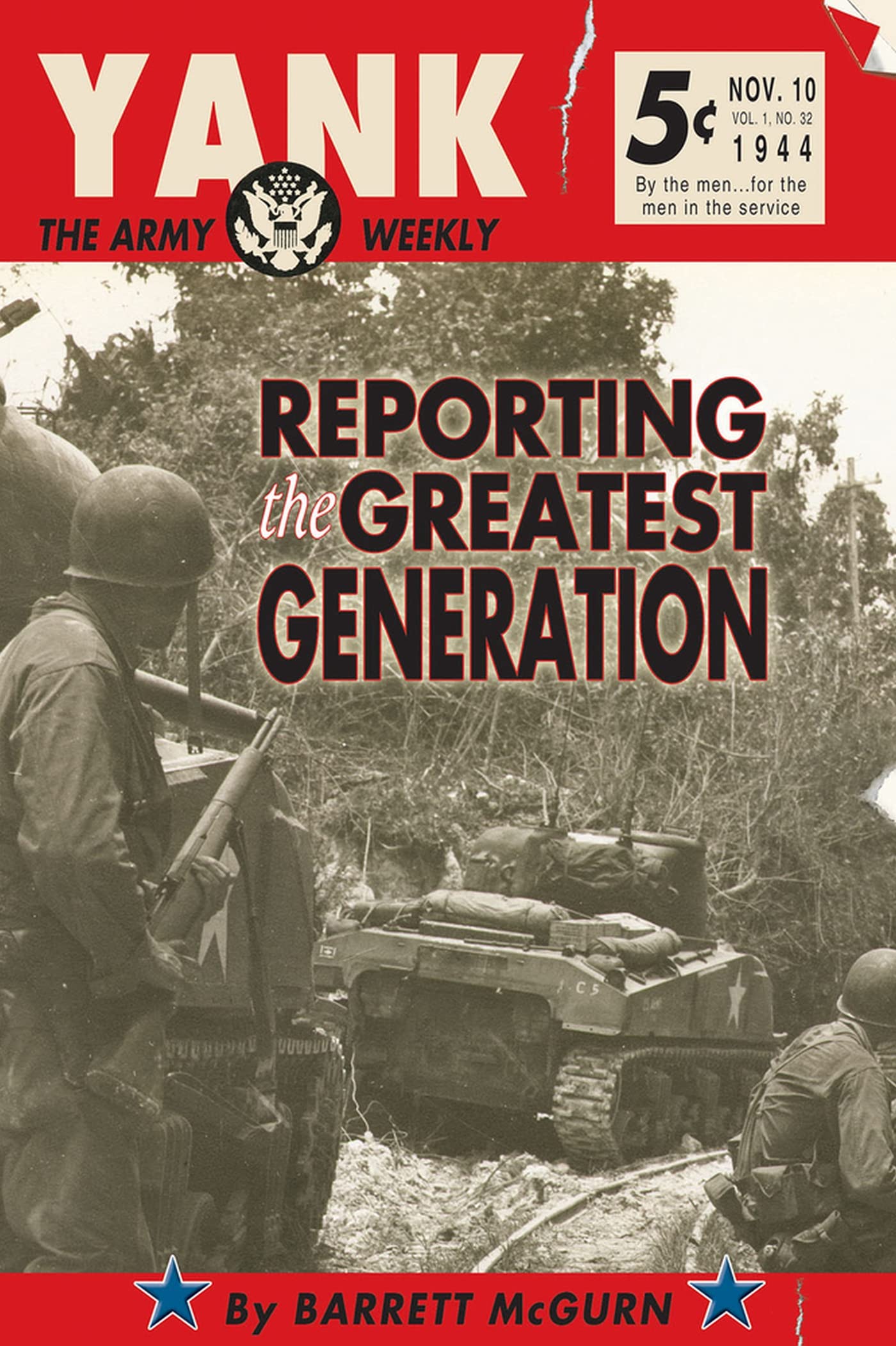

Here is the extraordinary story of the world's first global periodical-reaching troops on six continents-and history's most successful U.S. Army publication. Barrett McGurn was a reporter for the New York and International Herald Tribunes from 1935 to 1966. He served sixteen years as Bureau Chief in Rome, Paris, and Moscow, where he received journalism awards as the year's best foreign correspondent for his coverage of the French North African War of 1955 and the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. Preface YANK, The Army Weekly, was a phenomenon of World War II, which provided an insight into the nature of the American soldier that always will be valid. The WWII man in uniform was no superman, no jingoist. He was no different from those who came before or after him. He endured the months of boredom and the moments of terror that are a soldier s fate. He suffered while at the same time he and his comrades persevered because his country was under attack, just as it was on September 11, 2001, that "nine-one-one" day when the comforting telephone number for emergency help took on a sinister reverse meaning. YANK was the friend and colleague of the WWII soldier and was itself part of the enlisted U.S. Army. It let off soldier steam with "Mail Call" letters to the editor allowing troops to air their beefs at a global level. With its "What s Your Problem?" section providing frank, if not always the wished-for answers, it was a sort of secular chaplain. With its pinup pictures of gorgeous women back home, YANK spoke to the longings of young men who sometimes went months without seeing a woman. With its eyewitness staff reports of courage and death on battlefields around the world, the soldier weekly helped ease the strain of combat by sharing its very horror. YANK violated all military and journalistic logic. With a circulation of 2,250,000 and a readership double that number created entirely by privates, corporals, and sergeants without officer intervention, YANK was a major morale instrument and propaganda device not controlled by lieutenants, captains, majors, colonels, or even generals which indeed flustered some of America s own generals, including the blood-and-guts Patton and the centralist MacArthur. Caesar provided his own history of a "Gaul divided in three parts" and Britain s commander-in-chief Churchill recorded his particular version of World War II, but it was left to YANK s enlisted men to record America s own week-by-week diary of what the mid-twentieth century global war was like. YANK was the first periodical to achieve global publication. Faced with how to reach troops on six continents in timely fashion when transportation was scarce, slow, and imperiled, YANK s small staff set up 21 editions in 17 countries, the main magazine was edited in New York and a few pages were substituted locally. Army planes carried the main page forms to regional YANK editors and printers in Panama, England, Puerto Rico, Trinidad, Italy, China, Burma, Egypt, Iran, France, Strasbourg, India, Hawaii, Australia, Saipan, Okinawa, the Philippines, and even Japan. The magazine s staff was part of the Army and had its own small share in the 1945 victory, along with the bombers, the artillery, the infantry, and the warships. Yet it was not the size of a division, nor a regiment, nor even a battalion. It was simply a military company with its single six-stripe first sergeant ruling from inside an office building on Manhattan s East 42nd Street. From there the sergeant s troops, answerable to him, fanned out across the planet to man bureaus often of a single soldier in Iceland, Nassau, Greenland, British Guiana, the Alcan Highway, Alaska, the Fiji Islands, New Guinea, the South Pacific, China, North Africa, Newfoundland, Iraq, Burma, and, in the case of one lucky corporal, Bermuda. YANK was an official War Department publication and all but troops in combat had to pay to get it. The price was five cents or the local equivalent in a score of foreign currencies. The theory was that no one would read what he received for free. Unlike many other government documents, YANK was bought and read because it was believable. In a civilian Army, with all the indignities and frustrations of life under military discipline, it was accepted by the enlisted soldiers and sailors because its editors, writers, photographers, artists, and cartoonists shared the same lot and, if fortunate, bucked their same way up to more sleeve stripes of enlisted rank but never up to the gold shoulder bars of a second lieutenant. YANK was designed at the very top of the American war effort by Secretary of War Henry Stimson and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, as a way to let forcibly inducted civilians compare notes as they endured the separations and miseries of the war effort. One of the few times officers were allowed to contribute was when they spoke up in self-defense in the Mail Call replying to some subordinate s blast. In an era of no television,