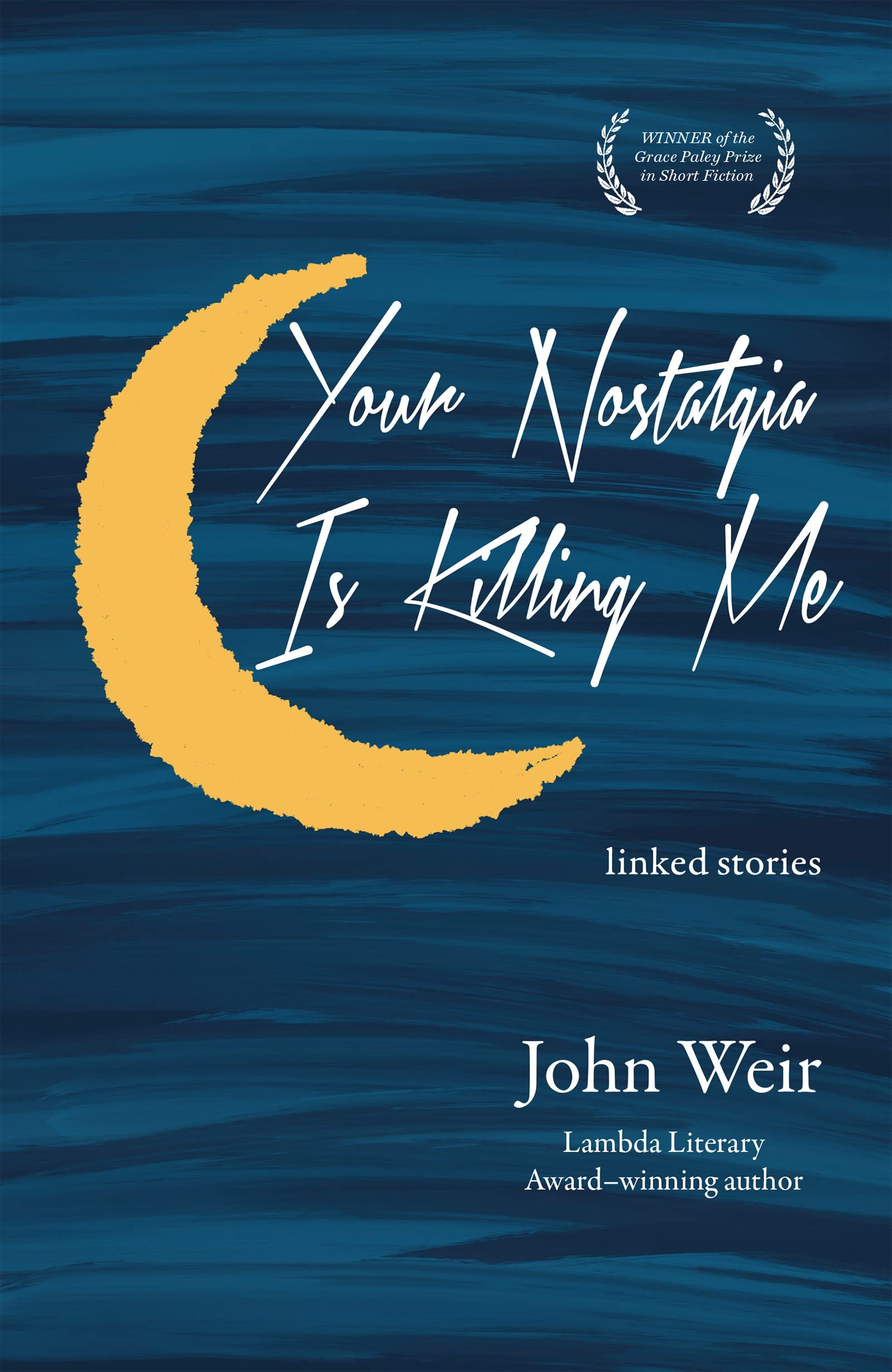

John Weir, author of The Irreversible Decline of Eddie Socket , a defining novel of 1980s New York in its response to the global AIDS crisis, has written a story collection that chronicles the long aftermath of epidemic death, as recorded in the tragicomic voice of a gay man who survived high school in the 1970s, the AIDS death of his best friend in the 1990s, and his complicated relationship with his mother, “a movie star without a movie to star in,” whose life is winding to a close in a retirement community where she lives alone with her last dog. “ Your Nostalgia is Killing Me is a witty short story collection. Eleven linked first-person short stories tell the story of a protagonist whose early adolescent experiences of homophobia in a small town and whose adult loss of his best friend to AIDS during the height of the epidemic write the script for his life, propelling him in and out of relationships with friends, loved ones, and lovers who expect too much or too little. Taking place at acting classes, cinemas, funerals, high school graduation ceremonies, plays, public protest demonstrations, retirement homes, and sex parlors, these eleven linked stories pull at the thin line between erasure and exposure, all the while skillfully highlighting the performative nature of death, grief, illness, love, masculinity, and sexuality against the backdrop of late twentieth-century US culture.” —Dr. Amina Gautier "Your Nostalgia Is Killing Me refocuses the lens of memory. Most reboots and reimaginings may evoke retro fashions and music, but the true voices of the times come from those, like Weir, who survived the not-so-distant past."— Foreword Reviews "This raw, unflinching work has a lot to offer."— Publisher's Weekly "Sharp, elegaic, angry, funny stories with a searing loneliness often just underneath the surface."— Kirkus "These eleven short stories are fast-paced with plenty of quick dialogue, pop culture, and political moments. Weir's collection is a history lesson, a survival story, and a study on how to occupy the space between."— Five South " Your Nostalgia is Killing Me is entertaining and heartbreaking by turns, always a gripping read."— North of Oxford "The linked stories span a 40-year period, illustrating the power of nostalgia to alternately bring us to tears and make us laugh with a familiarity that is sure to resonate with readers from all walks of life." — Bay Area Reporter and Grab Magazine "Weir is the Whitman of the Age of Aids, bequeathing us litanies in cascading trebles."—novelist Kate Rounds "Weir writes beautifully, and his wit, his keenly detailed observations, and his telling insights will resonate — at the very least for gay men of the generation we share. His ruminations about that untamed epidemic our world continues to face — unreconstructed masculinity — could hardly be more timely."— Gay City News "Weir writes beautifully, elegantly." — NY Journal of Books "With insight, eloquence, and wit, Your Nostalgia Is Killing Me refocuses the lens of memory. Most reboots and reimaginings may evoke retro fashions and music, but the true voices of the times come from those, like Weir, who survived the not-so-distant past." — Foreword Reviews John Weir , winner of the Grace Paley Prize for Short Fiction for Your Nostalgia Is Killing Me , is the author of two novels, The Irreversible Decline of Eddie Socket , winner of the 1989 Lambda Literary Award for Gay Men’s Debut Fiction, and What I Did Wrong . He is an associate professor of English at Queens College CUNY, where he teaches the MFA in creative writing and literary translation. In 1991, with members of ACT UP New York, he interrupted Dan Rather’s CBS Evening News to protest government and media neglect of AIDS. He lives in Brooklyn, New York. We parked behind a Peugeot in Cindy’s circular drive and chased the sound of voices down a slate path that led to the back of the house. The path widened and became a patio around a pool whose surface sparkled with heat and reflected moonlight. “Jesus,” Lottie said, either in warning or exclamation, or both. “Yeah, really,” I said, staring at the pool, the patio, the curtained French doors thrown open to the lawn, and at the tanned girls in halter tops and peasant skirts lounging in iron chairs at the poolside, and the boys in shorts and polo shirts standing in the living room by the liquor cabinet, mixing drinks with sneaky names—Slow Comfortable Screw, Sex on the Beach—and playing Bob Dylan on the stereo. At the edge of the patio, we stopped. I was careful to pause at the start of things. There was a chance I would giggle, or sing show tunes, or play with my hair. I had to remind myself to be cool. So far, none of the girls had seen us. Most of them were cheerleaders, like Cindy, and they could have been as far away as a football field, they seemed so out of reach. Still, some of them were my friends. I liked to hang out with girls because they were no